Robert M. Kaplan

Australia

|

|

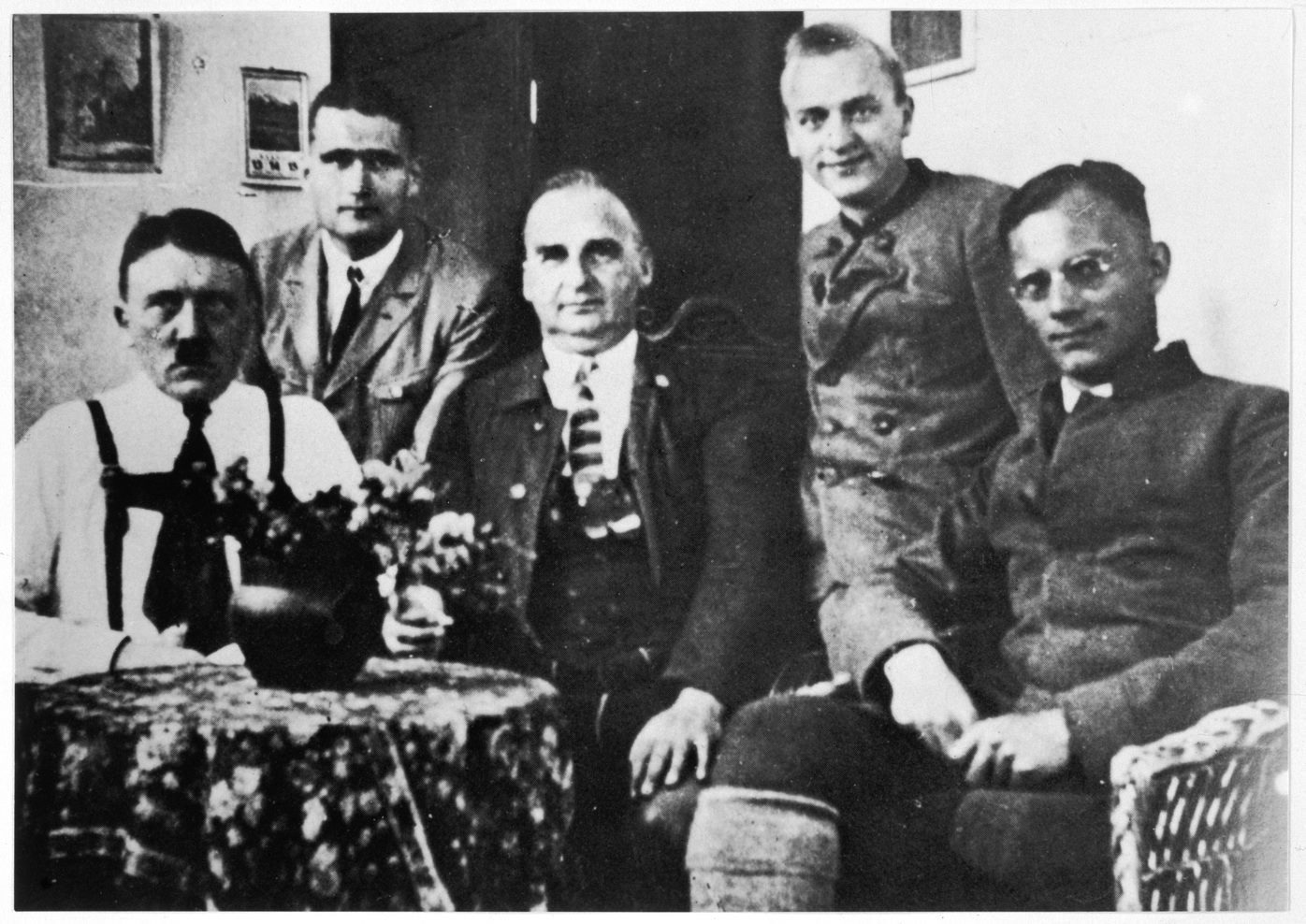

| Top: Hitler in Landsberg Prison common room with (from left) Hess, Herman Kriebel, Fobke and Dr. Friedrich Weber. Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo. Bottom: Landsberg Prison for War Criminals, 1933. Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo. |

It is perhaps not widely known that Adolf Hitler, one of the most fanatical and murderous personalities in history, underwent psychological treatment early in his political career. It happened in November 1924.

He was at the time a right-wing activist and rabble-rouser arrested after mounting a coup against the Bavarian government, the so-called Munich Beerhall Putsch. Taken to the Landsburg Prison, he was described as “a lump of misery,” unshaven, miserable, distracted, and expecting to be shot for treason or deported to Austria.

During the interrogations that followed, Hitler demonstrated his usual histrionic behavior. He would either remain silent or break out into crying fits. His shouts and screams could be heard all over the building. He “howled like a madman,” raving about “liars and traitors,” went on a hunger strike, and became apathetic and increasingly weaker.

Moved to the hospital wing, he was visited by the prison psychologist Alois Maria Ott. A devout Catholic, Ott was a firm believer in the power of goodwill, having a non-judgemental, empathic approach to his patients.

His first impression of the future dictator was unprepossessing. Hitler was a “scowl-eyed stocky man,” a “middle-class man with mannered black hair combed into his forehead and the well-known trimmed beard fly,” “a wide, ordinary mouth and a broadly protruding, somewhat indented nose.”

To remind him of reactions to the failed putsch, Ott showed Hitler the Bayerischer Kurier (Bavarian Courier) which reported a colleague accusing him of “falling victim to the devil of his own vanity and a prima donna complex.”

He leveled out the differences between the two, saying “Herr Hitler, I give you my word that I’ve told nobody in the prison that I was coming to see you, and nobody will learn anything of this conversation. You and I are about the same age and have both lived through war and misery. I’m coming to you man to man, to be of assistance, the same way I do with every inmate.”

Hitler, convinced that he was going to be shot, became more hysterical. “The people are a pack,” he cried. With “whitish-yellow flakes of foam on his mouth,” he intended to “wipe out his life on a hunger strike.” Distraught at the death of his comrades in the march, he shouted that “I have had enough, I am done, if I had a revolver I would take it.”

Ott made an assessment of his patient: a hysteric and pathological psychopath—the only psychiatric assessment of Hitler by anyone who examined him.

Not intimidated by the ranting and screaming, Ott intended to take control of the encounter. First, he lectured Hitler on the need to be patient about establishing his political program, only to receive another screaming tirade that Germany could not wait for this before he was crucified and burned at the stake.

Asked by Ott whether he had chosen the wrong role model in view of Austria’s recent history with the Hohenzollerns did the trick—the impasse was broken. On familiar territory, Hitler delivered to Ott a lengthy discourse on his interpretation of history and the two now had a basis for conversation.

From this point, they would debate current and past issues. “You must know,” said Ott, “how long it took the Prussian general staff to prepare for the last war, and that revolutionaries like Garibaldi and Mussolini need the will of the people behind them. Slogans, especially ideological ones like anti-Semitism and anti-clericalism, won’t bring starving people to the barricades.… Why do you and your followers spread hatred toward Jews and toward papal authority? We can be political opponents, but if you want to lead a whole nation into a better future, we need one another.”

This must be one of the very rare (if not unique) occasions when someone challenged Hitler’s fanatic and hate-filled views.

Predictably, Hitler contradicted Ott, but stayed engaged, stating that only two institutions required his respect—”the old Prussian General Staff and the Roman College of Cardinals.” It is interesting to see that the dictator, who could never be questioned or contradicted, responded to another view on this occasion.

Ott concluded by recommending a “pious recipe”: “Find back to the old order of God!”

It worked. Hitler stopped the hunger strike and returned to his comfortable room. In the trial that followed, he talked the judges down, making him a national figure. He was on his way to become the most terrible dictator the world has known.

Ott, who first disclosed his involvement with Hitler at the hearty age of 98, concluded that his patient had a “penchant for magical-mysterious thinking,” an opinion that is difficult to disagree with. Filled with “vanity and brutal dogmatism” Hitler’s hatred for “those who think differently” could not be attenuated: “I could feel his demonic obsession with an ideology that unleashed the psychopath in him.”

Hitler would seem to be the least likely person to respond to psychotherapy. Ott’s intervention succeeded because Hitler’s political career was at an early stage and the rampant megalomania he displayed once he came to power was still developing. Characteristically, his suicidal threats were a recurrent response to adversity.

Ott’s approach allowed his difficult patient to engage with him, followed by contradiction of his fervid opinions. He succeeded by not according Hitler any special status, treating him like any other patient with a mixture of confrontation, empathy and allowing opportunity to vent. Here lies a lesson for all psychotherapeutic encounters.

Ott did the right thing for his patient; what it meant for the world is another thing. We can only look back and wonder if there had been someone like Ott in Hitler’s life at other critical points whether history would have been different. If only…

Abstracted from a much more extensive review by Dr. Kaplan in the Psychiatric Times, June 25, 2020. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/alois-maria-ott-i-was-hitler-s-psychologist

ROBERT M. KAPLAN is a forensic psychiatrist, writer, and historian at Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia. His latest book The King Who Strangled His Psychiatrist and Other Dark Tales is waiting for a publisher.

Fall 2022 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply