Fung Kam Yan

Hong Kong

|

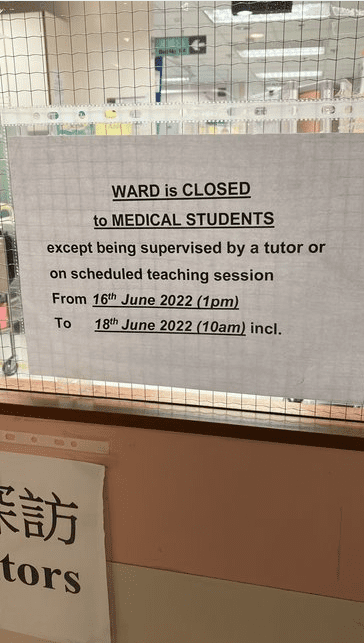

| Sign outside the author’s grandmother’s hospital ward. |

It was a Sunday. I sat outside the ward in my white coat, my eye protection fogging up, trying to catch my breath through the KF94 mask. My grandmother was inside, also struggling to breathe.

The nurse said that only two visitors were allowed because of COVID-19 restrictions. It did not matter that I was a medical student, and that medical students are normally allowed in this ward. It did not matter that we were all fully vaccinated and had tested negative for COVID-19. It did not matter that we all knew she was dying.

My father and aunt were inside, seeing her through a translucent plastic screen. No goodbye kiss or hug for her. So near and yet so far.

I sat under the harsh, white hospital lights for an hour. Doctors and nurses walked past me, wondering what a medical student was doing here on a Sunday. Or perhaps they were too busy with their work to care.

My father video called me. I saw my grandmother through the screen of my phone and the hard plastic screen around her bed. She could not hear me, but she recognized me. It is unprofessional to cry when you are in your white coat, I reminded myself. But she was only ten steps away, and I was not allowed in.

The first message had arrived the previous Friday: Your grandmother is in the hospital.

The second message had come on Saturday, a long audio recording from my aunt: Your grandmother has pneumonia, gallstones, and inflammation of her bile ducts. But because of her age and her condition, they can only treat her with antibiotics.

After my father’s visit with my grandmother was over, I ate lunch with him at the dingy hospital canteen. It was Father’s Day. He kept saying, “I don’t understand why cholangitis is so serious. The gallbladder is not that important. People can live without it.”

I drew him a picture of the liver, gallbladder, biliary tree, pancreas, and duodenum. I drew what happens normally, and what happens when the bile ducts are blocked. How doctors would normally drain it, why they could not do that for my grandmother, and what might happen if it was not drained.

On Tuesday, the third message came: Two visitors can come for a compassionate visit. She did not recognize us at first. “No more injections,” she cried. I saw her wrists, blue and black from all the blood draws.

I held her hand, stroked her back because she could not hear me. In moments of lucidity, she asked how my studies were going, and whether my father and I could collect the Hong Kong government’s consumption vouchers. She asked me how old I am because she always wants me to get married. Even while lying on a hospital bed, struggling to breathe, she was worried about her children and grandchildren.

On Wednesday, the fourth message came. My aunt’s voice, worried and uncertain, struggling to decide whether to place a feeding tube for my grandmother, knowing that eating was one of the few joys in life that my grandmother had left.

On Sunday, a week later, the final message came: Your grandmother has gone home to be with the Lord.

FUNG KAM YAN is a fifth-year medical student studying at the University of Hong Kong. Before entering medical school, she studied mechanical engineering at the National University of Singapore and worked a couple of years as an engineer. After that, she volunteered on the ship MV Logos Hope for five months. She hasn’t decided what she wants to specialize in, but she knows that she wants to volunteer with Mercy Ships and MSF in the future.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Fall 2022 | Sections | End of Life

Leave a Reply