Oyenike Ilaka

Albany, New York

|

|

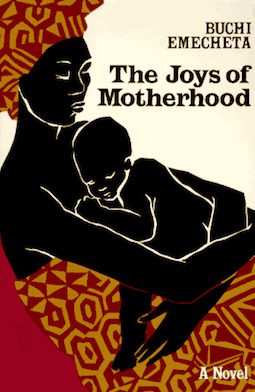

Cover of The Joys of Motherhood, published in London, UK, by Allison & Busby in 1979.2 |

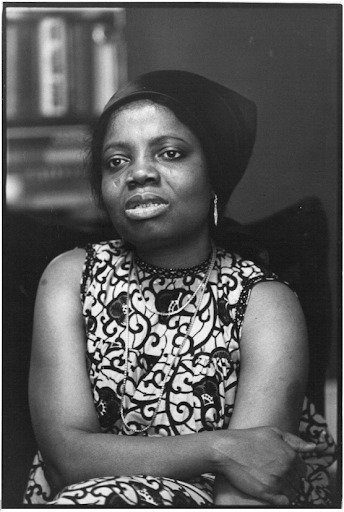

The Joys of Motherhood is a Nigerian novel written by Buchi Emecheta in 1979. Emecheta was a Nigerian woman from the Igbo tribe. Born in 1944, she spent her childhood in Lagos. At sixteen, she married and immigrated to London, where she discovered her passion for writing. Unfortunately, her husband was not supportive of her passion, and went so far as to burn her first manuscript. Lacking a supportive partner, she divorced her husband and became a single mother of five children. She attended University of London to study sociology and eventually became a full-time writer, publishing sixteen novels. Emecheta drew her inspiration from her life in colonial Nigeria and her experiences as a woman in the patriarchal Igbo culture.2,3

I first read Joys of Motherhood at age twelve. I remember becoming frustrated by the suffering of the protagonist, Nnu Ego. I did not understand why the book had such a title because I thought “The Hardship of Motherhood” would have been more fitting. Nnu Ego marries at sixteen and is replaced by a new wife when she does not conceive two years into her marriage. Disgraced, she leaves her village to remarry Nnaife, who is a laundry man to British masters in colonial Lagos. She becomes fertile and experiences the first death of a child, and the birth of many more, including a set of twins. She must raise these children despite her family’s worsening economic conditions. Nnaife later marries a second and third wife, and Nnu Ego begrudgingly accepts her role as the senior wife in her polygamous marriage. She works as a trader, and is praised by her numerous children as a loving, hard-working mother.2

As a more mature reader now, I realize the importance of the story and its relationship with the obstacles shared by black women in America and around the world. Black women in the United States share burdens of infertility, infant and maternal mortality, economic hardship, and lack of access of contraception. In colonial and present day Nigeria, having an abortion is illegal and access to contraceptives is not widespread, which can also be said of some jurisdictions of the United States in the present day. Black women are a marginalized group, facing many forms of discrimination including but not limited to racism, colorism, xenophobia, classism, and sexism.

|

|

A young Buchi Emecheta. Photo by Valerie Wilmer via Google Doodles.1 |

Infertility is a major theme. Nnu Ego is taunted by her chi and is unable to have a child in her first marriage.2 Chi is used to describe a small god that belongs to a particular person. She has a dream that there is a baby at the river, but she is unable to get to it. In American society, black women are stereotyped as hypersexual and hyper-fertile but continue to have less access to assisted reproductive technology (ART).4,5 They also have particular treatment needs, including a variety of diagnostic tests when battling infertility and uterine fibroids. The United States healthcare system can be considered a chi, taunting the black woman with fertility treatments that she cannot use.6

In the first and fifth chapter respectively titled “The mother” and “A failed woman,” Nnu Ego suddenly loses her firstborn and few-weeks-old infant and decides to end her life out of grief. She immediately runs out of her house, into the marketplace and towards a bridge, intending to jump into the lagoon to question her chi for taking away her motherhood. When questioned and prevented from her attempt to commit suicide, she exclaims, “But I am not a woman anymore! I am not a mother anymore. The child is there, dead on the mat. My chi has taken him away from me. I only want to go in there [the lagoon] and meet her….”2 She later bears many healthy children but experiences the loss of another child when she has a spontaneous abortion.

Her suicidality and the death of her children reflect the mortality of the black woman and her offspring. Maternal mortality remains a global issue, especially in areas of conflict and low- and middle-income nations.7 Sub-Saharan countries, especially Nigeria, are one of the most dangerous places for a woman to give birth.8 In the United States, black women are also three to four times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related death compared to white women.9

Before her death in 2017, Emecheta stated “Black women all over the world should re-unite and re-examine the way history has portrayed us.”13 Joys of Motherhood inspires me as an aspiring obstetrician and gynecologist to provide excellent care for all people, including the ones who share my cultural identity. I hope that women today, like Nnu Ego, can be hardworking and loving mothers and also follow their passions and live fulfilling lives.2

References

- Google Doodles. Buchi Emecheta’s 75th Birthday. July 21, 2019. https://google.com/doodles/buchi-emechetas-75th-birthday.

- Emecheta B. The Joys of Motherhood. Second ed. New York: George Braziller Inc.; 1979, 230.

- Robolin S. Introduction, The Joys of Motherhood. New York: George Braziller, Inc; 2013, 16.

- Luna Z. Black celebrities, reproductive justice and queering family: An exploration. Reprod Biomed Soc Online 2018;7:91-100.

- Treder K, White KO, Woodhams E, Pancholi R, Yinusa-Nyahkoon L. Racism and the reproductive health experiences of U.S.-born black women. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139(3):407-16.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: Burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med 2017;35(6):473-80.

- Bauserman M, Lokangaka A, Thorsten V, Tshefu A, Goudar SS, Esamai F, et al. Risk factors for maternal death and trends in maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries: A prospective longitudinal cohort analysis. Reprod Health 2015;12 Suppl 2:S5.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2(6):e323-33.

- Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61(2):387-99.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infant Mortality. June 22, 2022. https://cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm.

- UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Nigeria: Infant Mortality Rate – Total. 2021. https://childmortality.org/data/Nigeria.

- Matoba N, Collins JW, Jr. Racial disparity in infant mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(6):354-9.

- BBC News. “Buchi Emecheta: Nigerian author who championed girls dies aged 72.” January 26, 2017. https://bbc.com/news/world-africa-38757048.

- Nwakobi E. 25 Powerful Quotes By Buchi Emecheta. eelive. September 11, 2019. https://eelive.ng/25-powerful-quotes-by-buchi-emecheta/.

OYENIKE ILAKA is a third-year medical student at Albany Medical College and an aspiring obstetrician and gynecologist. She has lived in Nigeria, France, and the United States of America. Oyenike loves writing and has written some articles for Ayiba Magazine, an online platform that unites the African diaspora; and for a local nonprofit health center (Whitney M. Young Jr.).

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Fall 2022 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply