Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

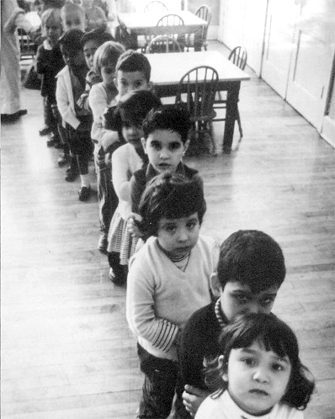

Cuban children in line to emigrate. Photo via DEFELIX on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0.

In 1959, lawyer and revolutionary Fidel Castro (1926–2016) overthrew the corrupt, US-supported government of Fulgencio Batista, the dictator of Cuba. Castro promised reforms and democracy. However, early in his regime, members of the Batista government were executed after pro forma trials. Businesses were nationalized in 1960, and the following year, all private schools were closed. The press was controlled by the government. Public religious services were banned. One thousand children were sent to the USSR and to Czechoslovakia for study and indoctrination. Priests and nuns were forced to leave Cuba. Cuban children five to thirteen years old were pressured to enroll in the “Pioneers”; those fourteen to twenty-one in a paramilitary youth organization.

There were anti-Castro Cubans soon after Castro seized power. These Cubans hoped that Castro’s government would be short-lived (that is, a few weeks), either because of a counter-revolution or a US invasion that would remove him from power. While they were waiting for this soon-to-happen event, they sent their children to the US. A few hundred children came early to the American “parking place.” The hopes of these parents were not, of course, realized.

Cuban parents were becoming increasingly worried (though still thinking the Castro government would fall) and wanted to send more children to the US. In 1960, “Operation Peter Pan” began. Father Bryan Walsh, a Catholic priest in Miami, and James Baker, the headmaster of a private school in Havana, arranged the transport of children to the US. Nearly all of the children arrived without their parents, who often stayed to take care of their own elderly parents in Cuba, and also because of the belief that the Castro government was temporary.

The US government made it clear that it did not want Castro to stay in place. American-supported radio stations told Cubans that the Castro government would end all parental supervision of children, turn them against their parents, and raise them in indoctrination camps. Allowing children to come to the US was a good propaganda tool, since it showed that life in Cuba was not easy, and it also helped to counter world opinion regarding the violent, racist civil rights battles taking place mostly in the US South.

In April 1961, the US supported (inadequately) a CIA-Cuban exile attempt to invade Cuba (the “Bay of Pigs” invasion) with the goal of removing Castro. It failed, and Cuban parents became less and less convinced of the temporary status of the Castro regime. Castro declared the revolution socialist. Diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba ended. Father Walsh was given carte blanche permission to issue US visa wavers to Cuban children to enter the US. The US government paid each child’s $25 ($250 in today’s money) plane fare. In 1962, flights from Cuba to the US ended.

The Cuban children who came unaccompanied to the US were of all ages, including infants. Most were between twelve and fifteen years old, 70% were boys, were from upper- and middle-class families, and were predominantly Catholic. They were white, Black, and Asian. Between 14,000 and 15,000 came to the US between 1960 and 1962. About 40% went directly to relatives in the US and the rest were placed in care, initially in group homes. The eight camps or group homes in Florida were quickly filled. Children were then placed in 100 cities in thirty-five US states and Puerto Rico.

There were tensions in Miami as the African-American community saw needed resources and jobs going to Cuban immigrants. Part of this may be explained by the notion that the Cubans were anti-communists, but some US civil rights leaders were accused of being “communist.”

Some of the group homes were problematic. At the least troubling end of the scale, some camps were overcrowded and had long lines to use the showers and toilets. In some places, nuns physically abused children. White and Black Cuban boys were separated in Louisiana. Some Cuban girls were used as servants in foster homes. A priest—who was later defrocked—sexually abused some children. Sexual abuse was also committed by a foster father and by school employees. Some children were neglected in foster homes.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 increased US-Cuban hostility. Between 1962 and 1965, Cuban parents could not visit their children in the US, nor could the children return to Cuba. In 1965, parents were again allowed to visit the US. Most of the “Pedro Pan” children did well. Ninety percent were reunited with their parents by 1966. One study comparing “Pedro Pan” children with children who immigrated to the US with their parents showed that these two groups of individuals, now in their sixties (about fifty years after immigration), had no differences in physical or mental health. Items inquired about were stroke, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, depression, and anxiety. The “Pedro Pan” children were “overwhelmingly…thankful that their parents sent them.”

[Most of the information in this article may be found in reference 1.]

References

- John Gronbeck-Tedesco. Operation Pedro Pan: The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba, Lincoln NE: Potomac Books, 2022.

- Deanna Palenzuela. Growing Up in Neverland: An Assessment of the Long-term Physical and Cognitive Correlates of the Operation Pedro Pan Exodus. [Thesis] Yale University. https://psychology.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/DeannaPalenzuela_SeniorThesis_GrowingUpInNeverland.pdf.

- Meghan Vail. Media Cold Warriors of Operation Pedro Pan: Examining the Impact of US Cold War Rhetoric on Contemporary US Foreign Policy Towards Cuba. [Thesis] University of Texas at Austin ScholarWorks, 2011. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/ETD-UT-2011-05-3495.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply