Desmond O’Neill

Dublin, Ireland

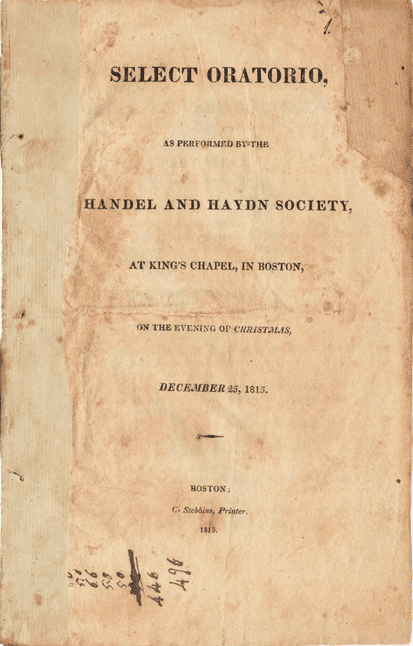

Although the very first performance of the Messiah took place in April 1742 in Dublin with the London première following in March 1743, the oratorio is closely associated with the Christmas season in the Anglophone world. The origin of this custom has been claimed by the Handel and Haydn Society in Boston arising from their first performance of the Messiah in the United States on Christmas Day in 1815. Medical associations were a feature of the work from its earliest origins, with hospitals in Dublin and London among the beneficiaries of the first performances, and the composition process influenced by one of the many strokes that Handel suffered during his lifetime.1

This work of genius is striking for its memorable tunes and affecting solos interspersed with compact powerful choruses, underpinned by effective but mostly restrained orchestration. The integrity of the whole is all the more remarkable given variety of musical influences, including the French overture, Italian recitative, English anthem, and German fugues, as well as the choices possible in selecting which numbers to include in a performance. A key element of its lasting success is the remarkable synergy between the music and the text by Handel’s librettist, Charles Jennens. In an increasingly secular world, the persistent popularity of this religious masterpiece points to universal messages of consolation, compassion and hope.

A fascinating aspect of seasonal performances of the Messiah is the degree to which the Christmastime elements appear to form a relatively small proportion of the work. Only the first of the three Parts is devoted to the prophesy and birth of Jesus, as well as his healing; the second Part traverses his passion and resurrection, and the final Part the promise of eternal life. However, this sequence has a logic in its own right in framing the joyous renewal of the Christmas season and hope of the coming new year in the context of not only the consequences for the year ahead but also the life-course and the eventual course towards fulfillment, death, and transcendence.

The predominance of Old Testament texts is paralleled in the German Requiem by the agnostic Johannes Brahms, often signaled as the first great secular requiem. Both great masterworks also eschew the emphases of judgement in the classical requiem tradition, instead radiating solace and comfort for the living.

For the medical humanities, the impact of these texts, the majority from the Old Testament provide a fascinating opportunity to re-emphasize the Bible as great literature and not exclusively as a text of doctrinal exposition.2 A useful lens for this reading is the concept of methodological atheism described by Jürgen Habermas, where the focus is on the content and not on their dogma.3 Surprisingly little has been drawn formally from the great religious texts in terms of insights into medicine, with tantalizing prospects in the slender literature on patient-physician communication,4 public health,5 music therapy,6 and moral injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.7 Wider study also aids us in understanding the philosophical and metaphysical elements of human spirituality.

A focus on great music associated with these texts, and their enduring appeal in pluralist societies with secular institutions, is an optimal gateway to consider exploring the rich complexity of their content, metaphors, and paradoxes.8 To hear the Messiah in the Christmas season reminds us that this music is uniquely capable of providing a common space and shared experience of the mysteries of birth, life and death, love and loss, and meaning which mark our personal and professional lives.

References

- Evers S. Georg Friedrich Handel’s strokes. J Hist Neurosci. 1996 Dec;5(3):274-81.

- Ryken L. How to Read the Bible as Literature:… and Get More Out of It. Grand Rapids, Michigan, Zondervan Academic, 1984.

- Cooke M. Salvaging and secularizing the semantic contents of religion: the limitations of Habermas’s postmetaphysical proposal. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 2006;60(1):187-207.

- Schattner A. The book of Genesis and physician-patient communication. Neth J Med 2020;78(2):94.

- Mazokopakis EE. The prevention of cholera in the Bible. Vaccine 2019;37(35):4850.

- Mazokopakis EE. Music as a Medicine for the Soul in Bible and Christian Patristic Tradition. J Relig Health 2020;59(3):1217-1219.

- Grimell J. Contemporary Insights from Biblical Combat Veterans through the Lenses of Moral Injury and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J Pastoral Care Counsel 2018;72(4):241-250.

- Lloys T. Hope in the Unified Language of Music: Teaching Sacred Music in a Secular Context. Choral Journal 2007;47(9):34-39.

DESMOND O’NEILL, MD FRCPI, is a professor in Medical Gerontology, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 2 – Spring 2023

Leave a Reply