Michael Yafi

Houston, Texas, United States

|

|

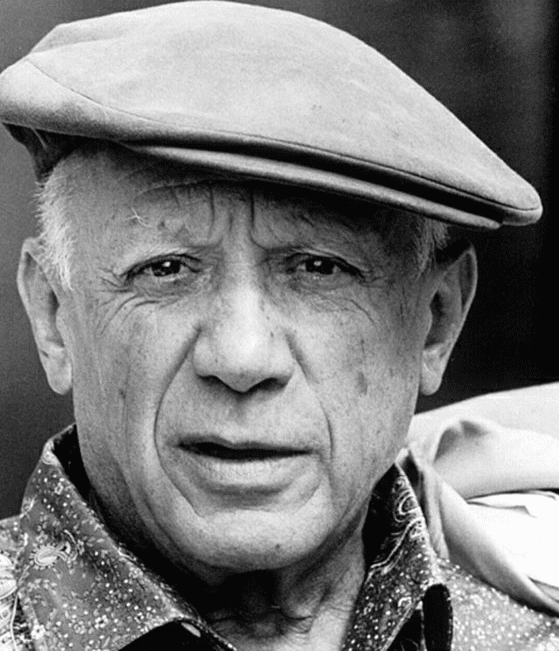

Pablo Picasso in 1962. Photo via Wikimedia. |

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881–1973) was known for his love of the good life. Reportedly, his last words were “Drink to me!” But early in his life, Picasso witnessed sick and dying friends and relatives in his hometown of Malaga, Spain, and was haunted by the deaths of his sisters. Cholera, diphtheria, and other bacterial infections were common,1 and painting became a way for Picasso to document his losses. This is depicted in three of his early works: The Sick Woman (1894), Science and Charity (1897), and Last Moments (1899).

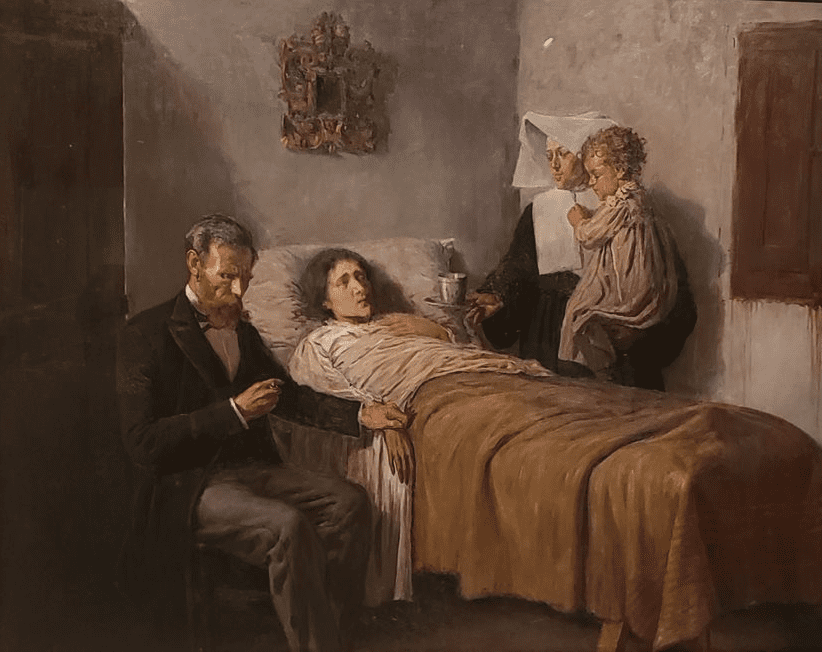

Picasso’s paternal uncle, Dr. Salvador Ruiz, was a respected physician who supported him financially to enroll in the art school at the Instituto da Guarda. The director, Dr. Ramon Perez Couteles, was also a physician.1 This may have started Picasso’s fascination and respect for medicine. He painted Science and Charity when he was fifteen, showing a sick patient attended by a physician measuring his pulse (Science) and a nurse carrying a child while offering the patient empathy (Charity). His 1907 Head of the Medical Student depicts a figure with one eye open and one eye closed,2 a symbolic effect of examining reality while dreaming of innovation.

Picasso also suffered from migraine, and there have been many attempts to connect his cubism painting style to his experience of migraine auras.3,4 A recent paper suggested coining a term, “Pablo Picasso syndrome,” when describing the auras of some migraineur patients who experience metamorphopsias, or distortions in size (micropsia/macropsia), and distance (teleopsia) of body parts.5

|

|

Science and Charity. Painting by Pablo Picasso, 1897. Museu Picasso, Barcelona, Spain. Photo by author. |

References

- Katz JT, Khoshbin S. “Picasso’s Science and Charity: Paternalism Versus Humanism in Medical Practice.” Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016 Mar 9;3(4): ofw056. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw056. PMID: 27747249; PMCID: PMC5063546.

- MacKenzie MA. “Ethics of Being Close.” AMA J Ethics. 2021 Jul 1;23(7): E580-581. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2021.580. PMID: 34351270.

- Gandhi JS. “Pablo Picasso and aspects of medicine.” Am J Med. 2013 Dec;126(12):1150-1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.042. PMID: 24262728.

- Haan J, Ferrari MD. “Picasso’s migraine: Illusory cubist splitting or illusion?” Cephalalgia. 2011 Jul;31(9):1057-60. doi: 10.1177/0333102411406752. Epub 2011 May 13. PMID: 21571758.

- Suri R, Ali A. “Coining the Pablo Picasso Syndrome.” Headache. 2020 Mar;60(3):626-629. doi: 10.1111/head.13702. Epub 2020 Jan 19. PMID: 31957015.

MICHAEL YAFI, M.D., is a Professor and Director for the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at UTHealth (The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston).

Summer 2022 | Sections | Art Flashes

Leave a Reply