Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

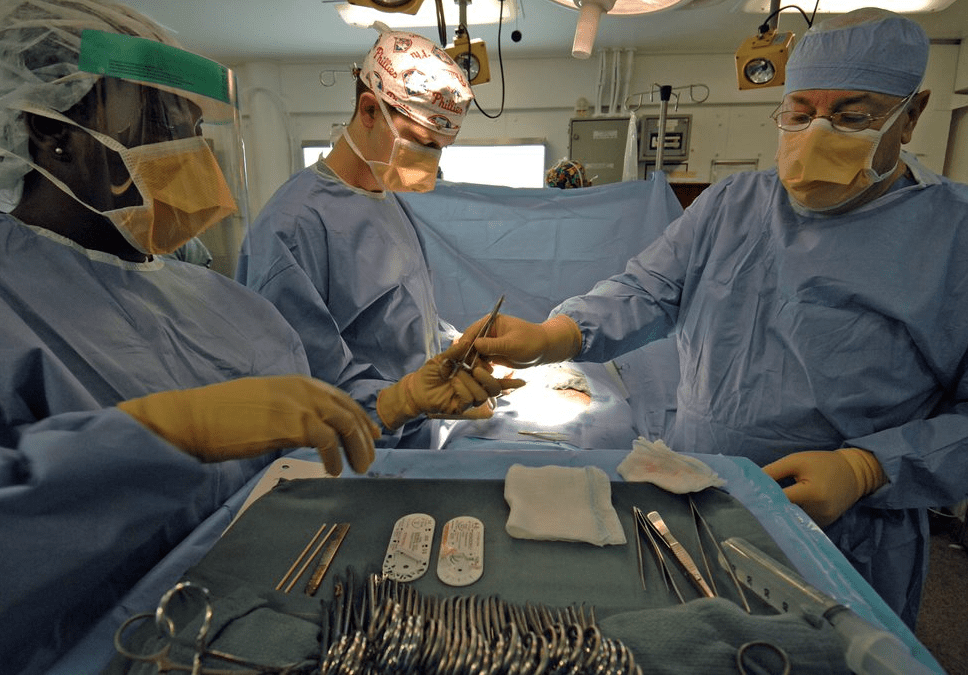

| Surgeons operating aboard the USS Harry S. Truman. US Navy photo via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

“Medicine is power. It makes us giants.”

– Dr. Daniele Valotti in Bisturi: La Mafia Bianca

Bisturi: La Mafia Bianca (1973) is an understated, well-acted, and critical “doctor movie.” Unlike The Hospital, it is not a black comedy of errors, and unlike Where Does It Hurt? it is not a broad, obvious satire. It is different from Article 99 since it does not portray dedicated doctors fighting administrators and the bureaucracy.

Italian Dr. Daniele Valotti (played by Gabriele Ferzetti) is a respected surgeon, called by everyone “The Professor.” He is tall, handsome, well-spoken, and has a voice and a manner that inspires confidence. On rounds he is followed by a dozen physicians, both staff doctors and residents. He has a chauffeur-driven Mercedes a block long.

He sees “charity patients” one day a week, and sometimes operates without charging a fee. In response to their praise and thanks, he says, “I’m a doctor, a simple medical man.” On the other hand, he has employees whose job it is to discover the contents of the bank accounts of his rich patients. He takes a bribe of eighty million lire—$40,000—from a pharmaceutical company representative who needs a positive evaluation of a new medication made by his firm.

Valotti is told by a physician-researcher in his hospital that some foreign medical journals have published reports about the drug’s worrisome side effects. Valotti responds that the drug will act differently in the Italian climate. Later that day he lectures medical students on “the shame of serving lucrative ends.”

Surgeon Valotti tells five patients who are going to surgery at the same time that he will perform their surgeries. It is obviously impossible. He does one of the surgeries, and the rest are performed by other surgeons, one of whom operates on the wrong kidney. He knows that the nurses are charging patients to give them priority in receiving blood transfusions, and that the blood bank director is getting a “cut” of these bribes, but Valotti does nothing about it.

A young woman dies during a badly done surgery. Later that week, Valotti is called out of surgery to speak to the tax authority about his (probably falsified) income tax reporting. While he is on the phone, the man on the operating table dies. The next day, his widow throws herself from a fifth-story window.

The police are informed that repeated incidents of malpractice happen in this hospital. The informant is a colleague and co-worker of Valotti, Dr. Giordani (Enrico Maria Salerno), who has seen enough. Valotti arranges it so that Giordani will perform a surgery, but gives him another patient’s X-rays, concealing the fact that any surgery would be fruitless and dangerous. Valotti offers to keep this death quiet if Giordani will withdraw his accusations of malpractice. Giodani says that he sees that Valotti has Parkinson’s disease, which is worsening, and that he must stop operating. The viewer is left with the impression that Valotti’s career is over. We do not know what will become of the malpractice charges.

This is a believable film about greed, power, and corruption. Before the credits are shown at the end of the film, there is a written statement on the screen stating that the great majority of doctors try to “alleviate the suffering of humanity.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply