Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“In all the years I’ve been a therapist, I’ve yet to meet a girl who likes her body.”1

– Mary Pipher, PhD, clinical psychologist

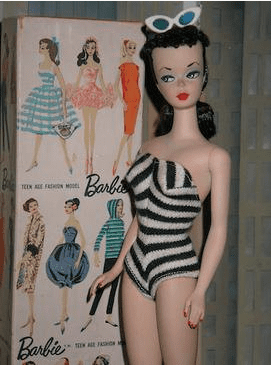

In 1959, the Mattel toy company introduced a doll in the US that was not modeled on a baby or small child, but rather on a young adult. The doll, named Barbie, was described as a “teen-age fashion-model.” The Barbie doll was based on a German doll, Lilli, who had originated as a comic strip character. Lilli was not a sex toy, as some authors have stated, but in the comic strip she appears to be “a high-class call girl.”2 Over one billion Barbies have been sold in over 150 countries. In 2020, Mattel made $1.35 billion from the sale of Barbie dolls and accessories.3

However, the physical proportions of the Barbie doll do not represent or reflect the bodies of healthy women. If a standard (11.5-inch tall) Barbie doll was given an adult height of 5 feet, 9 inches, she would have a waist circumference of about 18 inches. For comparison, the professional tennis player Serena Williams has an approximately 28-inch waist, and singer Lady Gaga about a 26-inch waist.4 Barbie, if she were human, would not have the required amount of body fat to menstruate.5 Her shoe size would be a disproportionate US 3, or a 34.5 in Europe. Instead, Barbie’s long legs were designed to make her look like a “a pin-up,”6 rather than a child’s toy. The Barbie doll has been described as “biologically impossible” with her hourglass figure, “preternaturally large” breasts,7 “long thighs, full lips and great hair.” The anatomical impossibilities continue, as she also has “no nipples and no genitals.”8

“Barbie doll syndrome” (or simply “Barbie syndrome”) is a type of body dysmorphic disorder, which has been described as the drive to attain impossible standards of physical appearance such as that of the Barbie doll.9 The impossibility of attaining this has “caused great physical and mental problems in the minds of young girls.”10

Among three- to eleven-year-old girls in the US in 1996, 97% had Barbies, with seven dolls on average. In France, the number was 86% with an average of two dolls, and 98% in Germany, with three dolls per child.11 A study in the U.K. in 200612 exposed five- to eight-year-old girls to images of Barbie dolls, normally proportioned dolls, or no doll at all. The younger girls in the Barbie-exposed group reported lower self-esteem and a greater desire to be thin. A similar study was done in the Netherlands13 with 117 girls, aged seven to eleven years. After playing with Barbie (rather than a normally proportioned doll), that group of girls ate less when offered food. A study of American college women found that when they compared themselves to Barbie or to fashion models, they had a decline in self-esteem, a more negative body image, and an increase in risky sexual behavior.14

Thus, some girls and young women who take Barbie as a role model may develop a “body image disturbance” (also called “body image distortion”) in early adolescence. They may have an altered perception of their physical appearance, along with dissatisfaction, anxiety, shame, and contempt for their bodies. A body image disturbance is one of several criteria for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.15 In the 1980s, a designer for Mattel said that “Barbie has become an obsession for little girls.” A speaker at a 1996 conference said that physicians and psychologists “are accusing Barbie of making little girls anorexic in their desire to look like Barbie.”16 In a 2001 article from India, Misquitta17 wrote, “[The] presence of a strong model for slimness in the form of the Barbie doll…may be a factor for the emergence of the disorder [anorexia nervosa] in our population.”

Another criticism of Barbie is as a role model for consumption. Her “lifestyle” implies that happiness comes from expensive material objects, and that a woman needs to be rich, pretty, and always having fun. Every activity needs a special outfit, even for “suburban shopping.”18

The influence of Barbie cannot be ignored. A popular, global toy for more than sixty years, Barbie, along with other media and cultural influences, may be a contributing factor to body image disturbances in some girls and young women. While there are likely multiple forces at work, in extreme cases this may play out as it did for one sixteen-year-old girl, who at age eleven wanted to be the “skinniest, prettiest Barbie,” and had a cardiac arrest as her first sign of anorexia nervosa.19

References

- Trina Bautista. “Self-esteem and sexual risk: determining if a relation exists among college-aged heterosexual women,” [thesis], 2015. California State University ScholarWorks.

- Kate Lister. A Curious History of Sex, London: Unbound, 2020.

- “Barbie.” Wikipedia.

- Courtney Frydryk. “Body image and Barbie,” Ohio Journal of School Mathematics, 75(1), 2017.

- “Barbie.” Wikipedia.

- Marianne Debouzy. “La poupée Barbie,” Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, 4, 1996.

- Catherine Driscoll. “Chapter fourteen: Girl-doll: Barbie as puberty manual,” Counterpoints, 245, 2005.

- Anna Kéchy. “The female grotesque in contemporary American culture,” Atenea, 1999.

- “Barbie.” Wikipedia.

- Rabia Sohail and Sumera Shan Ahmad. “The globalized Barbie effect on cultural wealth of communities of color,” Jahan-e-Tahqeeq, 5(2), 2022.

- Debouzy, “La poupée.”

- Helga Dittmar and Emma Halliwell. “Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of five- to eight-year-old girls.” Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 2006.

- Doeschka Anschutz and Rutger Engels. “The effects of playing with thin dolls on body image and food intake in young girls,” Sex Roles, 63(9), 2017.

- Bautista, “Self-esteem.”

- “Body image disturbance.” Wikipedia.

- Debouzy, “La poupée.”

- Neville Misquitta. “Anorexia nervosa: A Caucasian syndrome rare in Asia,” Med J Armed Forces India, 57(1), 2001.

- Debouzy, “La poupée.”

- Sian-Lee Ewan and Patricia Moynihan. “Cardiac arrest: First presentation of anorexia nervosa,” BMJ Case Rep, 2013.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023

Leave a Reply