Mel Ebeling

Birmingham, Alabama, United States

|

|

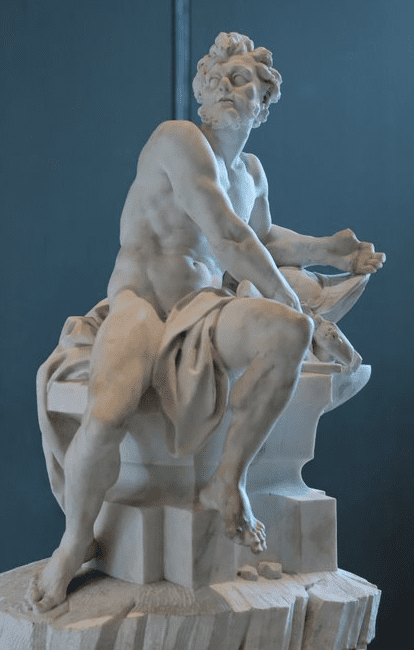

Hephaestus at the Forge. Sculpture by Guillaume Coustou the Younger, 1742. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen (Jastrow) on Wikimedia. Public domain. |

The same prominent scar blemishes each foot: beginning two inches below my big toe, it slithers along the medial aspect of my foot, making a hairpin turn around my ankle before coming to an abrupt halt on the opposite side, two inches below my pinky toe. I have bilateral congenital talipes equinovarus, more commonly called clubfoot, a musculoskeletal deformity that left both of my feet contorted at birth and has only been partially remedied by surgical reconstruction.

The intricacies of this surgery could be described as poetic, but the pain I experience makes my condition feel much that much more crude, unsophisticated. A walk across campus and my tarsals are shattered by sledgehammers. Make it roundtrip and my tendons are sliced by razor blades. Standing and walking come at a price, a price that grew exponentially during my transition to adulthood and has become increasingly harder to pay. With age also comes my bitter acknowledgment of the truth—I am disabled.

As I begin to enter the field of medicine, I cannot help but stare down at my feet with great trepidation. The issue is not whether I meet the technical standards for becoming a physician—I can do the job—I just need to sit whenever I can. Instead, my apprehension lies with questions about the perceptions of my colleagues and preceptors. “Disabled” is a loaded and stigmatizing term, and physicians are not immune from perpetuating this stigma. When I sit down while rounding on patients, will I be viewed as lazy or uninterested? Or even worse, incompetent? If I sit on a stool during a surgical rotation, will I be labeled weak-willed? If I make my accommodations known, will these perceptions crumble or be fortified?

Yet, medicine revolves around the alleviation of human pain and suffering: who better to empathize with patients than a physician who has experienced not just a fleeting moment of pain, but a lifetime of it? Perhaps this is reason enough to be open about my condition to the medical community. Though here I am met with a harrowing realization of equal consideration: nobody wants what they see as a broken toy.

Even with legal protection from discrimination, the law cannot prevent unconscious bias. Medical school is hard enough, but my primary concern is not memorizing the Krebs cycle or the muscles in the body. Instead, I worry about the degree to which I will be discriminated against and how it will affect my career. In the meantime, I slip on a pair of high-top Converse to hide my scars and quicken my pace to mask my abnormal gait. What others do not know will not hurt them—it will only hurt me. That is what my lidocaine cream is for.

MEL EBELING holds a B.S. in neuroscience and is a first-year medical student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine. They are published in both the realms of scientific research and literary criticism. Outside of school, Mel enjoys serving their community as an EMT.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply