Simon Wein

Petach Tikva, Israel

The dog is a man’s best friend. Cats, horses, cows, rabbits, dolphins, and rarely goldfish are also good friends to humans, but none compare with the dog. In support of this contention, there are many wonderful books and films about dogs. The other animals, especially horses, are also the subjects of great works, but it is the relationship and ability to communicate that press home the righteousness of calling a dog a man’s best friend.

Black Beauty by Anne Sewell1 is a fabulous story about a horse that loved and suffered and was rescued and loved again. It opened people’s eyes to animal cruelty but perhaps anthropomorphized the horses too much. Steinbeck’s story of The Red Pony from 19372 was more about the difficulties of human relationships and used the horse as a vehicle. He did not get into the horse’s head, as it were. Then there is AB ‘Banjo’ Patterson’s classic poem, ‘The Man From Snowy River,’ from 1890. The man was heroic, but Patterson makes no bones about the courage and pride of the mountain bred pony—with a take home message:

But his hardy mountain pony he could scarcely raise a trot,

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur;

But his pluck was still undaunted, and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.3

What is the essence of the power and universality of the canine-sapiens relationship? It is surely unquestioning loyalty, devotion, protectiveness, sincerity, and response to love—from the dog. That’s enough, and a pretty good paradigm for the virtues required for successful relationships between humans. Of course, man must return these affections and virtues to the dog in order for the relationship to bloom.

There are true stories of dogs wandering thousands of miles home after being lost for months; of a dog waiting faithfully at the train station for years for a deceased owner to take him home. Dogged loyalty and devotion.

There are many wonderful books about dogs, but three that I know of have incomparable endings. I do not want to review the books in toto, rather the concluding chapter of each book. Each finale is brilliantly memorable and in its way successfully sums up the whole book and almost overshadows it.

Jack London of the US West Coast wrote White Fang in 1915.5 It is a superlative novel, the best of these three. London described the dogs as dogs, not as people portrayed as dogs. It was recently made a movie. White Fang the domesticated wolf-dog reminds us that just like animals, mankind can become like the wild when circumstances are ripe. The difference is that we must strive for goodness, as London sees it, and will be rewarded. The wolf-dog almost lost his life in service of his beloved man-god. Loyalty, love, trust, and rewards are reciprocally passed from dog to man. And justice prevails.

The second dog book is The Jewish Dog by Asher Kravitz from Israel, published in 2007.6 It is a Holocaust story with an unforgettable happy-sad ending that includes a respectful upbraiding of God to boot. There are two main themes in the book: the Holocaust (in which the Germans derisively called the Jews dogs) and the ‘human’ relationship between the boy-man and the dog after all their relatives had been killed by the Germans. The final chapter is glorious. It describes how man and dog can die of a broken heart together and how God can be upbraided for allowing such tragedy to befall his (and the dog’s) people. God cedes the final argument and acknowledges the injustice in His Kingdom.

The third book is a little tedious in the middle parts until the final chapter, which is utterly poignant, captivating, and realistic. The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be by Farley Mowat is a memoir published in 1957 in Canada.8 Its final chapter opens with the man after breakfast following the dog’s morning walk. It was winter and cold and he followed Mutt the dog as the dog walked by each station of his haunt. And here Mutt did this, and there that happened, and…and…The dog’s final walk was a summary of his life’s adventures as outlined in the previous chapters. The man noted that Mutt was old with arthritis and experiencing a general slowing down of his bodily functions, including hearing. Mutt did not notice a big truck as it roared down a back road.

The beauty of Mowat’s book is its simplicity, a sense of a dog’s life very well lived, a review of the important byways of Mutt’s journey, recounted without sentimentality. So should all men and women meet their maker after a good life replete with meaning. Mowat describes the good life, the best of lives, with minor ‘technical’ challenges along the way, but a life lived well, enjoyed, and looked back on prosperously and fondly.

Kravitz describes a burning desire for justice to be both seen to be done and to be done in the face of evil. With man’s inhumanity to man, he prefers the reliability, faithfulness and sincerity of a dog. He seeks the high moral ground with God and is vanquished. London, typical for him, saw life as a Darwinian struggle for survival of the fittest. Heroism and courage are the sinew and fibre of the survivor. Yet despite the violence and harshness of life, London believed in justice and goodness. This is why at the end of the book he changes White Fang’s name to Blessed Beast, a paradoxical name metaphorical for humankind’s strengths and limitations.

It is curious. As much as we write about dogs and our relationships with them, we still write about and reveal ourselves. Inexorably.

References

- Sewell, Anna. Black Beauty. 1877. UK: Wordsworth, 1998.

- Steinbeck, John. The Red Pony. 1937. UK: Penguin, 2017.

- Patterson, AJ ‘Banjo’. “The Man from Snowy River.” 1890. All Poetry. https://allpoetry.com/The-Man-from-Snowy-River.

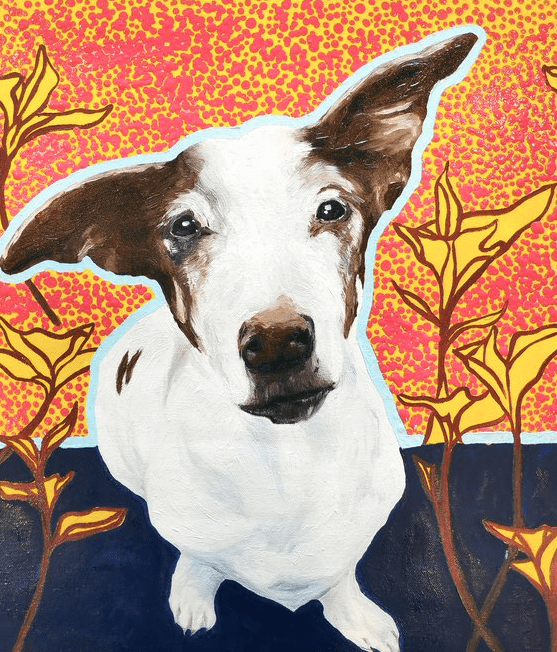

- Ricardo. Daniel Wein. Used with permission. https:// danielweinart.com/gallery?pgid=kzm15ndr-553c1848-d572-4f3d-a129-41336e09346d.

- London, Jack. The Call of the Wild & White Fang. 1915. UK: Wordsworth, 1998.

- Kravitz, Asher. The Jewish Dog. 2007. New York: Penlight Publications, 2015.

- Spotty. Daniel Wein. Used with permission. https:// danielweinart.com/gallery?pgid=kzm15ndr-f8bc344a-a8df-4d08-8ad5-4a9a63f2610a.

- Mowat, Farley. The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be. 1957. Lincoln, US: David R. Godine, 2017.

SIMON WEIN, MD, graduated medicine at the University of Melbourne and subsequently specialized in medical oncology, psycho-oncology, and palliative medicine. Currently he directs the Pain and Palliative Care Service at the Davidoff Comprehensive Cancer Center at Beilinson Hospital, in Israel. His main interests are the interaction of psychological and physical symptoms, improving the interaction of palliative care with medical oncology, and educating the next generation of oncologists.

Leave a Reply