JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

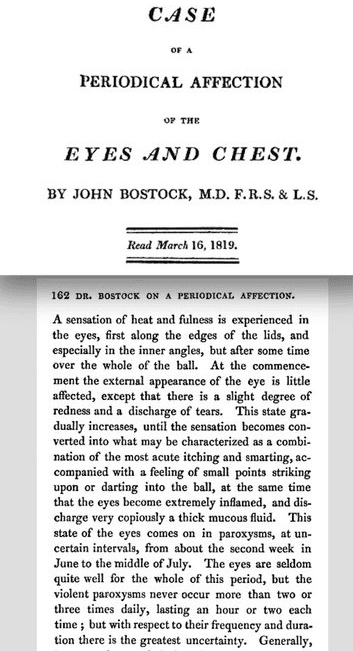

| Fig 1. Bostock’s paper to Medico-Chirurgical Transactions of London, 1819. |

Before the 1800s, hay fever, now estimated as affecting 5–10% of Western populations, was not widely recognized by physicians. James MacCulloch MD FRS, a doctor and geologist, in 1828 was the first to use the term hay fever, which he said was “a well-known disorder.”1 The surgeon William Gordon used the term “hay-asthma” in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal of 1829. He did not use the term hay fever but clearly described its symptoms of red, itchy eyes and sneezing, which preceded asthmatic wheezing. Unaware of pollen as the cause, he ascribed hay asthma to the scent of grass, hay, and flowers.2

Ten years earlier, John Bostock, whose name is now almost unknown, read a paper to the London Medical and Chirurgical Society on 16 March 1819: “Case of a periodical affection of the eyes and chest.”3 (Fig 1) It is generally reported as the first description4 of what Bostock later called “catarrhus aestivus” or summer catarrh, which soon became known as hay fever. He commented: “Except a single observation of Heberden’s, I have not met with anything that can be supposed to refer to it in any author, ancient or modern.”5,6 William Heberden (1710–1801) had described the disorder in 1802 in a chapter on catarrh:

I have known it (catarrh’s) return in four or five persons annually in the months of April, May, June, or July, and last a month with great violence. In one a catarrh constantly visited him every summer; and in another this was the only part of the year in which it ceased to be troublesome.7

Even earlier, Leonardo Botallo (1530–1587) of Piedmont and Pavia (noted for the eponymous foramen ovale or “foramen Botalli” and ductus arteriosus or “ductus Botalli”) described the disorder in his book De catarrho commentarius (Paris, 1564). The symptoms, precipitated by the “odor of roses,” are recorded in his Opera Omnia, Leyden 1660:

I have known men in health who directly after the odor of roses have a headache, or it causes sneezing, or induces such a troublesome in the nostrils that they cannot for the space of two days restrain themselves from rubbing them.

Bostock reported a patient, “J. B. aet. 46,” who was Bostock himself. He lucidly described how since the age of eight, in June and July each year he was subject to violent paroxysms of redness, itching, and smarting of his eyes with sneezing attacks and a copious mucous discharge. He tried many remedies but was “doubtful whether any distinct or permanent benefit has been derived from any of them.” However, confining himself to the house for six weeks reduced the symptoms.

During the next nine years he collected another 28 cases, which he again described to the London Medical and Chirurgical Society in April 1828.8

With respect to what is termed the exciting cause of the disease, since the attention of the public has been turned to the subject, an idea has very generally prevailed, that it is produced by the effluvium from new hay, and it has hence obtained the popular name of the hay fever.

Bostock thought that it was merely a summer variant of “the common catarrh.”9 John Elliotson had identified emanations from the flowers of grass as the cause of hay fever in 1831. Forty years later, Charles Blackley, himself a sufferer, by applying pollen directly to his eye established that pollen was the cause of hay fever,10 a fact unknown to Bostock. The term allergy (from the Greek ἄλλος ἔργον: other work) was introduced in 1906 by von Pirquet.

John Bostock MD FRS (1773–1846)

|

| Fig 2. John Bostock MD. Lithograph by William Drummond. Scottish National Portrait Gallery. CC BY-NC 3.0. |

Bostock was clearly an eminent physician. Pettigrew gave an excellent account of his life and works.11 Born in Liverpool, his father John Bostock was also a Liverpool physician and FRS. In 1792, the younger Bostock attended Joseph Priestley’s course of lectures and studied as an apothecary before graduating MD in medicine in Edinburgh in 1798 with a thesis on the secretion of bile. He was admitted an Extra-Licentiate of the College of Physicians of London in March 1770. He was elected FRS in April 1818.

He was appointed physician to the Liverpool General Dispensary where he built a fine reputation, enhanced by his role in the foundation of the botanic gardens, the Fever Hospital. He married Ann Whitehead in 1813; they had three children.

Bostock published numerous medical case reports. In the early 1800s, J. Blackall, and W.T. Brande had described proteinuria in dropsical patients, and W.C. Wells had realized it derived from the serum.12 In patients with kidney diseases Bostock reported diminishing levels of urea in the urine and rising levels in the serum, while the albumin in the serum diminished and its levels rose in the urine. In Richard Bright’s famous account of glomerulonephritis in 1827 he described coagulable urine, edema, and uremia in nephrotic renal disease; he quoted an earlier Bostock letter, which also described the nephrotic syndrome.

In 1817, Bostock moved to London and gave up clinical practice, devoting himself to chemistry and physiology. He lectured in chemistry at Guy’s Hospital where he associated with Richard Bright and Thomas Addison. He wrote influential medical textbooks. The first, Elementary System of Physiology (1824–1827), was succeeded by A Sketch of the History of Medicine from its Origin to the Commencement of the 19th Century (1835).4 He became vice-president of the Royal Society in 1831–2. He had a keen interest in geology and served as president of the Geological Society in 1826. Treasurer of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of London, he also served on the Councils of the Linnean, Zoological, and Horticultural Societies, and the Royal Society of Literature.4

On 6 August 1846 he died of cholera at his London home, 22 Upper Bedford Place, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Author’s note

I am indebted to Elizabeth S.S. Steinhart who first drew my attention to Bostock’s work.

References

- MacCulloch J. An essay on the remittent and intermittent diseases. London, Longman, 1828;1:394-7. Cited by Waite KJ. Medical History 1995, 39: 186-196.

- Gordon W. Observations on the Nature, Cause and Treatment of Hay Asthma. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1829; (2):513-515.

- Bostock J. Case of a periodical affection of the eyes and chest. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions of London 1819;10:161-165. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2116437/pdf/medcht00109-0169.pdf.

- Ramachandran M, Aronson JK. John Bostock’s first description of hay fever. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(6):237-40.

- Hurwitz SH. The Lure of Medical History: John Bostock (1773-1846): Author of the First Clinical Description of Hay Fever. Cal West Med. 1929 Aug; 31(2):137-8.

- B., W. Hay Fever. Nature 1923;111: 812–814.

- Heberden, William. Commentaries on the History and Cure of Disease, 4th edition, London, Printed for Payne and Foss – Pall Mall 1816.

- Bostock J. Of the Catarrhus Aestivus or Summer Catarrh. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions 1828;14:437–446.

- Finn R. John Bostock, hay fever, and the mechanism of allergy. Lancet. 1992 Dec 12;340:1453-5.

- Blackley CH. Experimental Researches on the Causes and Nature of Catarrhus Aestivus (Hay-Fever or Hay-Asthma). Oxford: Oxford Historical Books, 1873.

- Pettigrew TJ. Biographical Memoirs. London. Whittaker and Company 1839. Cited by Hurwitz.5

- Cameron JS. John Bostock MD FRS. Physician and chemist in the shadow of a genius. Am J Nephrol 1994; 14: 365–370.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply