Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“The greatest tragedy in the whole story of occupational diseases.”1

– Donald Hunter, M.D. (1898–1978)

The development of cheap, reliable, and reasonably safe matches became possible with the addition of white phosphorus (P4O10) to the match head mixture. The first factory to use white phosphorus (also called “yellow phosphorus”) in match manufacturing opened in 1836 in Stockholm.2 The substance was also used in the production of fireworks and munitions. Most workers in match factories were women (75%)3, some as young as fifteen years old. They worked fourteen hours a day,4 inhaling phosphorus fumes in poorly ventilated factories.

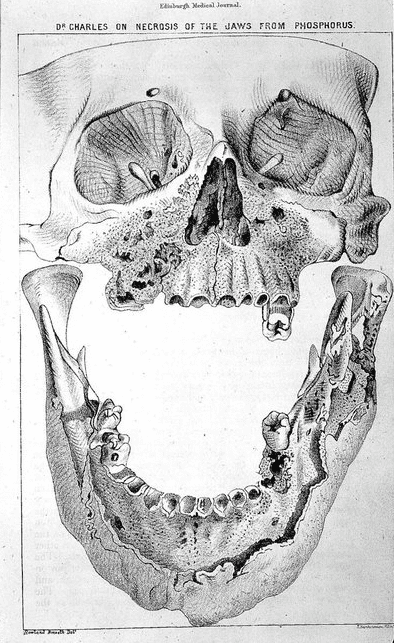

Their faces, hands, and clothing became contaminated with phosphorus particles. In 1838 the first case of a particular form of phosphorus toxicity, known in English-speaking countries as “phossy jaw,” or phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, was diagnosed in Austria.5 The illness started as a toothache, progressed to gingivitis, and then fistulae opened from the oral cavity to the skin. Tooth loss followed. After three months, bone in the lower jaw started to die, leaving an island of dead bone (a sequestrum) surrounded by less affected bone. After six months, more bone would show significant necrosis.

Words do not adequately describe the pain and disfigurement the patients suffered.6 The condition was sometimes called “matchmakers’ leprosy,” and these victims were ostracized like lepers.7 The smell of the necrotic tissue and of the drainage was so bad that family members could not stay in the same room with the patient.8,9 Tooth loss and pain made eating difficult, and the victim’s nutrition and general condition suffered.10 Aspiration of toxic secretions could lead to phosphorus bronchopneumonia. Seizures and meningitis were also seen. The bone marrow and the immune system were damaged by phosphorus.11,12 Atrophy of the eye sometimes occurred.13 Spontaneous fractures of the femur, tibia, or clavicle could happen.14 A Belgian physician saw thirty cases of long bone fractures in men with phosphorus necrosis of the jaw over a twenty-year period.15

A review of case records from Zürich from 1867–188916 showed a female preponderance of patients with “phossy jaw,” and a mean age of thirty years. Symptoms began five years after starting work with white phosphorus. The mandible was affected in about 75% of patients. In others, the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible were affected. Mortality was as high as 40%. Treatment involved mutilating surgery with removal of part or all of the affected structures.

It required more than thirty years to prohibit the use of white phosphorus in match production. The first country to ban it was Finland (then a part of Russia) in 1872, followed by Denmark (1874), and France in 1897.17 In the U.K., despite a strike by match workers in 1888 and the efforts of William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, to start a match factory in England (1891) that used nontoxic red phosphorus in match production, the use of white phosphorus continued until 1910.18 Canada did not ban white phosphorus in the match industry until 1914, even though phossy jaw had been seen in Canada as early as 1880.19

Had preventive measures been taken once the cause of jaw necrosis was suspected, much suffering could have been avoided. Such measures include frequent oral and facial washing, better ventilation, reduced working hours, and separate work- and break-rooms. The exclusion of workers with dental caries would have been important, since the phosphorus fumes often entered through these breaches.20

The citation that started this article is from Dr. Donald Hunter, a recognized authority on occupational diseases. He may well be right.

References

- Marc Müller et al. “Phossy jaws: an old occupational disease – up to date?” Saarland University, 2006. https://publikationen.sulb.uni-saarland.de/handle/20.500.11880/20871.

- Kjell Torén et al. “Tändsticken som gav arbetarna käkbensnekros.” Läkartidningen, 2001. https://lakartidningen.se/aktuellt/kultur-2/2021/02/tandstickan-som-gav-arbetarna-kakbensnekros/.

- Müller et al. “Phossy jaws.”

- Genevieve Carlton. “Inside ‘phossy jaw,’ the deadly condition that plagued the 19th century matchstick girls.” All That’s Interesting, 2021. https://allthatsinteresting.com/phossy-jaw/.

- Christine Jacobsen et al. “The phosphorus necrosis of the jaws and what we can learn from the past.” Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 18(1), 2012.

- Jacobsen et al. “Necrosis.”

- Carlton, “Inside.”

- Lowell Satre. “After the march girls’ strike: Bryant and May in the 1890s.” Victorian Studies, 26(1), 1982.

- Torén, “Tänksticken.”

- William Dearden. “Fragilitas ossium amongst workers in Lucifer match factories.” BMJ, 2(2013), 1899.

- Jacobsen et al. “Necrosis.”

- Müller et al. “Phossy jaws.”

- NA. “History of osteonecrosis of the jaw.” Pocket Dentistry, 2015. https://pocketdentistry.com/history-of-osteonecrosis-of-the-jaw/.

- J Hüghes et al. “Phosphorus necrosis of the jaw: A present-day study.” Brit J Industry Med, 19(83), 1962.

- Dearden, “Fragilitas.”

- Jacobsen et al. “Necrosis.”

- “Phossy jaw.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phossy_jaw.

- Carlton, “Inside.”

- Kathleen Durocher. “‘Phossy jaw’ au Canada: L’utilization du phosphore blanc dans les fabriques d’allumettes canadiennes, aux XIXe et XXe siècles.” Strata University of Ottawa Graduate Student History Review, ND.

- Jacobsen et al. “Necrosis.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply