JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

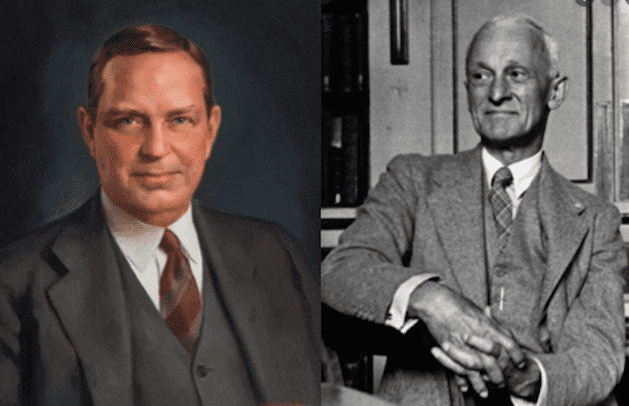

| Figure 1. Walter Edward Dandy (left) and Harvey Cushing (right). Dandy from Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Portrait Collection.2 |

In the history of American neurosurgery, two names stand out from the rest: Harvey Cushing (1869–1939) and Walter Edward Dandy (1886–1946). Sadly, they were inveterate rivals.

Dandy was undoubtedly a brilliant pioneer of both neurosurgical research and practice. He was born in in a small house on 5th Street, Sedalia, Missouri, an area where English immigrants lived and worked on the railroads. His father, John, was a train driver who had emigrated from Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria in 1883.1 His mother, Rachel (née Kilpatrick), was a quiet, determined Irish woman, devoted to Walter, her only child. They were both members of the evangelical Plymouth Brethren. Dandy, though not religious, was influenced by their humane values.2 He would write to them: “Long ago I realized that greatness was not frills and superficialities but the real true blue of unselfish devotion.”

Dandy excelled both as student and athlete at the University of Missouri, graduating AB in 1907, and MD from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1910. While still a student, he impressed the celebrated professor William Stewart Halsted (1852– 1922), who directed him to the Hunterian Laboratory where he worked under Harvey Cushing for a year. But their temperaments clashed, for both were brilliant, personally ambitious, and vain.3 When Cushing left Hopkins to go to Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, he decided against taking Dandy. Their mutual acrimony lasted many years.4 Halsted decided that although there was no obvious vacancy, Dandy should stay and work with pediatrician KD Blackfan (1883–1951) to investigate infantile hydrocephalus and the physiology of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

In 1914, Dandy and Blackfan published an exemplary, lengthy account of the pathogenesis and management of hydrocephalus.5 Halsted his mentor commented: “Dandy will never do anything equal to this again. Few men make more than one great contribution to medicine.” Subsequent studies of Dandy proved Halsted wrong. At Johns Hopkins, after his internship and residency, he was appointed assistant professor of surgery. He joined the Johns Hopkins University faculty in 1914 and remained there until his death.6 He built a team (his “Brain team”) of gifted trainees but drove them relentlessly with excessively long hours, rare holidays, and at times ill-tempered outbursts of anger. He introduced several new neurosurgical techniques, and in 1923 created a 24-hour specialized nursing unit for critically ill neurosurgical patients that is considered a forerunner of intensive care units.

Air encephalography and ventriculography

In 1916, attempting to improve the localization of brain tumors, he injected radio-opaque dyes into animals obtaining excellent pictures, but the dyes were toxic. He therefore tried with success to use air as a contrast medium. He applied this crucial discovery in 1918 by X-raying patients after injecting air into the cerebral ventricles through burr holes or via the infant fontanel: the original air ventriculography.7 This technique (at first criticized by Cushing) proved invaluable. A year later he devised air encephalography, with elegant pictures of the ventricular system by injections of air into the lumbar subarachnoid space, later developed by E. Graeme Robertson.8 These techniques long predated arteriography and later brain scanning and were able to clearly demonstrate both space-occupying and atrophic lesions of the brain.

Surgical forays

Ivatury lists his remarkable range and number of operations.4 His exceptional surgical skill attracted visitors from around the world. He would often operate on five patients with brain tumors in a day. But he and Cushing clashed again when Cushing drastically reduced the 70–80% surgical mortality of cerebellopontine angle tumors to 11% by extracapsular removal. Dandy used a suboccipital total excision with a similar mortality rate.9 Before 1913, Dandy always acknowledged Cushing’s papers; after this year his name appears no more. Dandy devised a retroganglion neurotomy for trigeminal neuralgia with fewer incidents of facial palsy and keratitis than achieved by the retro-Gasserian neurectomy of Frazier and Spiller.

With Blackfan in 1914, he described the Dandy-Walker syndrome: a congenital malformation with hypoplastic cerebellar vermis, ballooned roof of the fourth ventricle, high tentorium, and hydrocephalus, later elucidated by Earl Walker.

Having shown that the choroid plexuses secrete cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), he studied CSF secretion and absorption with phenolic dyes and refined surgical procedures, including choroid plexectomy for aqueduct stenosis.10

Dandy also pioneered surgery for intracranial aneurysms, which he observed had been “always considered rare and almost impossible both of diagnosis and treatment.” Early attempts were unsuccessful, but in 1937 Walsh and Love performed a successful carotid ligation. In the same year, Dandy was the first to apply a silver clip successfully to ablate a posterior communicating artery aneurysm.

In 1924, Dandy, via a retro-mastoid craniotomy, boldly severed the acoustic nerve with consequent deafness but relief of intractable vertigo in Ménière’s disease; he later performed selective vestibular division. In 1928, he reported nine operations for “persistent aural vertigo” and again for “persistent tinnitus,” all successful.

Before Mixter and Barr’s classic paper of 1934 that introduced intervertebral disc surgery, he described the clinical features and surgery of lumbar disc protrusions11 with such extraordinary confidence that because 98% of all lumbar disks were at L4-5-S1 levels, he insisted it was unnecessary to use contrast media to diagnose such cases. He recorded central disc protrusion as a cause of bilateral sciatica and spinal canal block that demanded immediate treatment.

Six years before his death, he was performing over 1000 major operations per year. Not least of his legacy to neurosurgery, he wrote 169 papers and five books,12 including a classic text, Surgery of the Brain (1935).

Walter Dandy

Dandy often worked alone. Like many prima donnas, he was thought to be dogmatic, abrasive, and insensitive. He was a dedicated teacher and a perfectionist, but failed to conceal his anger when colleagues’ management did not match his own high standards. Gilbert Horrax, a friend, wrote to an aggrieved colleague: “Come, Come, face up to it. The big complaint we have against Dandy is that he is twenty years ahead of the rest of us.”

Outside the hospital, he was a devoted, generous family man.13 In 1924, he married Sadie Estelle Martin, a dietetic social worker at Johns Hopkins, whom he met while waiting for an elevator; they had three daughters and a son, Walter Dandy, Jr., who became an anesthetist. His home was his refuge. His relationship with Sadie and their children was a source of great joy. He was a mischievously playful and loving father, sharing and leading his children in games.2 Many saw only one side of his personality, for he was always sure of the correctness of his own views and often contemptuous of opposing ones; he was also shy and at times aloof.

On April 1 1946 he had a heart attack, treated at Johns Hopkins but a second attack a fortnight later proved fatal. Geoffrey Jefferson’s British Medical Journal obituary noted:

Dr. Dandy excelled his early master, Harvey Cushing, whose assistant he had been in the latter’s Johns Hopkins phase, his beginning. No surgeon has ever been bolder than Dandy in his designs (as in excision of the cerebral hemispheres), a boldness usually justified by successes where none had been won before.

On his death, the journal Surgery dedicated two volumes for “Dr. Walter E. Dandy Birthday Number” in May and June of 1946 with an introduction by Blalock and contributions from friends and admirers from the US and abroad. The Walter E. Dandy Neurosurgical Society was founded in November 2011 in St. Louis, Missouri, his birthplace.

References

- Harvey AM. Neurosurgical Genius – Walter Edward Dandy. Johns Hopkins Medical Journal 1974;135:358-68.

- Dandy-Marmaduke ME. [Dandy’s eldest daughter]. Walter Dandy: The Personal Side of a Premier Neurosurgeon. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

- Pearce JMS. Walter Edward Dandy (1886-1946). J Med Biogr Aug 2006;14(3):127-8.

- Ivatury RR. Our Surgical Heritage: Walter Edward Dandy—The Founding Father of Neurosurgery. Pan-American Journal of Trauma, Critical Care & Emergency Surgery 2021;10(3):121-125.

- Dandy WE, Blackfan KD. Internal hydrocephalus, en experimental, clinical and pathological study. American Journal of Diseases of Children 1914;8:406-82.

- Obituary. Walter Edward Dandy. Journal of the American Medical Association 1946;130:1257.

- Dandy WE. Ventriculography following the injection of air into the cerebral ventricles. Annals of Surgery 1918;68:5-11.

- Robertson EG. Pneumoencephalography. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas, 1957.

- Dandy WE. An operation for the total removal of cerebellopontine (acoustic) tumors. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, Chicago, 1925;41: 129-48.

- Dandy WE. Diagnosis and treatment of strictures of the aqueduct of Sylvius (causing hydrocephalus). Arch Surg 1945;51:1-14.

- Dandy WE. Loose cartilage from Intervertebral Disc simulating Tumour of Spinal Cord. Arch Surg 1929;19(2):660.

- Troland CE, Otenasek FJ. Selected Writings of Walter E. Dandy. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas,1957.

- Barnes W. Walter Dandy MD. Personal Reminiscences. Neurosurgery 1979;4:3-6.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply