JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

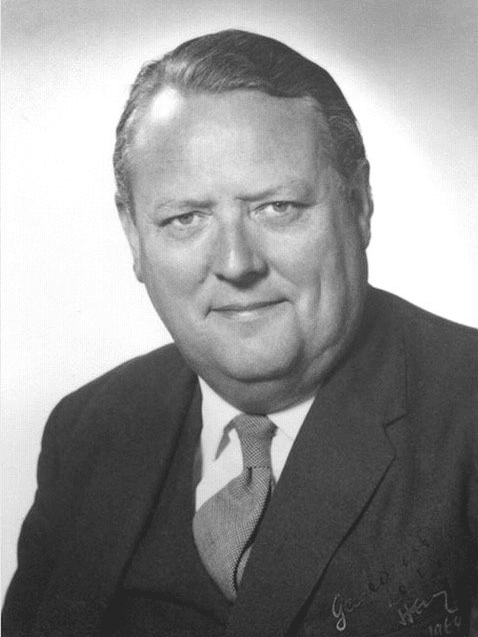

| Henry Miller. From the author’s personal collection. |

There are many eminent figures in the worlds of medicine and neurology, most of them distinguished by their clinical skill, academic prowess, scientific originality, or success in establishing major institutes of teaching and research. Henry Miller (1913–1976), though not a laboratory investigator, was blessed with many of these attributes, but beyond that he was in more senses than one a great and inspiring man.

Born in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, the son of an engineer, John, and his wife, Mabel Isobel (née Bainbridge), his schooling was at the Grammar School at Stockton-on-Tees. He studied medicine at the University of Durham College of Medicine in Newcastle upon Tyne, qualifying with honors in 1937. Even as a student, his genial extroversion and popularity were reflected in his election as president of the University Union. He held training posts at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle, the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Great Ormond Street Hospital before serving in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War as a neuropsychiatric specialist with the rank of squadron leader.

After demobilization he further trained at Hammersmith Hospital and at the National Hospital, Queen Square. In 1947, he returned to Newcastle as assistant physician to the Royal Victoria Infirmary and was appointed consultant neurologist, becoming Reader in 1961. Relinquishing a successful private practice, he was appointed Professor of Neurology in 1964. Two years later, he was appointed Dean of Medicine and in 1968, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Newcastle upon Tyne until his death.

He rapidly expanded his neurology department and was an active clinical investigator of multiple sclerosis and its epidemiology. He gave an important if controversial analysis of traumatic or “accident neurosis” in the Royal College of Physicians Milroy Lectures, published in April 1961, which became the subject of editorials in The Times and The Lancet.

He attracted many talented acolytes; many of them attained eminence in neurology, most notably John Walton in 1958 and Jack Foster in 1963. Walton’s many illustrious contributions culminated in a knighthood and elevation to the peerage as Lord Walton of Detchant.

|

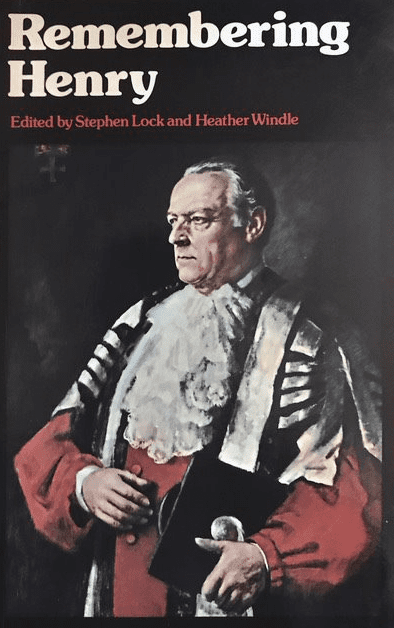

| Cover of Remembering Henry, edited by Stephen Lock and Heather Windle. |

Henry Miller was a gregarious man of great style and wit, who wore his enviable learning lightly. He was a gifted writer with a masterly handling of language. His contributions were elegantly expressed with wisdom mingled with wry humor and a capacity to disdain pretentious or ill-founded items of received doctrine. His books included Early Diagnosis (1960), Modern Medical Treatment, and Medicine and Society. He was joint editor of Progress in Clinical Medicine, which went through eight editions, and with WB Matthews he wrote an excellent, concise textbook, Diseases of the Nervous System. In all he penned more than 200 scientific papers on medicine and neurology. He frequently contributed educational articles in The Listener, and Encounter. His “Fifty years after Flexner” (Lancet Sept 1966) sought to review and advance the organization of medical education.

His teachings in the clinic were laden with wise, intuitive diagnostic inferences; his memorable lectures were hugely entertaining. Medicine to Henry was fun. This sense was so infectious that he was adored by his students and trainees, and locally known as Henry Gorgeous Miller. As vice-chancellor, his skill in handling the student body was unrivalled. However, those of too serious a disposition or indifferent in their clinical performance were rapidly dismissed as “dead wood.” Aided by his considerable influence, many of his juniors became established in senior posts in neurology.

He was well versed in opera and the arts, and a bon viveur with a love of food and wine, which he generously shared with friends and juniors. When distinguished visitors from abroad came to lecture in Newcastle, he would take them out to dinner with a few carefully chosen senior colleagues but also a party of his juniors thereby privileged to meet such famous figures. Rather than charging this legitimate expense to departmental funds, he would put his hand in his pocket to pay the bill.

In all his endeavors he was wonderfully supported by his wife Eileen, herself a gynecologist, with whom he had two sons and two daughters. He never fully recovered from a heart attack and died in congestive heart failure at home. The small book Remembering Henry contains a series of touching tributes, personal stories, and recollections, edited by Stephen Lock and Heather Windle, published by the British Medical Association in 1977.

There have been very few physicians whose example as men of intellect, generosity, and wit could match that of Henry Miller.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply