J. Gordon Frierson

Palo Alto, California, United States

|

| Autographed portrait of Chevalier Jackson. Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0. |

One day, in the tough coal-mining city of Pittsburgh of the early 1900s, two Sisters of Mercy brought an emaciated, severely dehydrated, seven-year-old girl to a doctor’s office. Sometime earlier the girl had swallowed lye, thinking it was sugar, and the ensuing inflammation and scarring had all but blocked her esophagus. The doctor, alert to the problem, reached for a new instrument he had designed himself, an esophagoscope. Through its narrow bore he saw the scarred food passage, cleared a mucous plug for immediate relief, and gradually dilated the esophagus. The girl, rescued by the novel procedure, grew into normal adulthood.

The physician who related this moving story was Chevalier Jackson, one of the most interesting, and lesser known, medical practitioners in America. Jackson was born in 1863 and grew up on a poor farm near Pittsburgh. He and his two brothers filled their childhood days with farming chores and their evenings with reading, primarily books on science. But school was a torment. Jackson shared classrooms with sons of coal miners and farmers, a rough crowd that bullied the conscientious student constantly. He escaped only through his hobbies, wood-working and drawing, which he pursued in a small workshop at home. After high school, he commuted an hour each way by train to attend the Western University of Pennsylvania (later the University of Pittsburgh), while still helping on the farm at home.

Jackson decided on a career in medicine. His parents were now bankrupt, and drawing on his art skills, he decorated lamps and shades to earn tuition. He entered Jefferson Medical College in 1884 for the two-year curriculum: a six-month set of identical lectures each year. He lived in an attic room where he cooked his own frugal vegetarian diet. To finance his second year, Jackson sold medical books and later signed on to a cod-fishing boat. He received his hard-earned MD degree in 1886.

At Jefferson, the professor of laryngology, Jacob Solis-Cohen, the author of an authoritative text on diseases of the nose and throat, had recently created a laryngology clinic. Solis-Cohen noticed Chevalier’s interest in the new specialty and loaned him his copy of the works of Sir Morell Mackenzie, the most prominent laryngologist in England. Eager to study from the best, Jackson cobbled additional scanty funds together and sailed through a rough storm to England. During the journey, smallpox broke out on the vessel and Jackson’s efforts caring for the stricken patients earned him a bonus sufficient to pay for a return trip. In Mackenzie’s clinic he watched procedures with newly created laryngoscopes and esophagoscopes. On return, he opened a laryngology practice in Pittsburgh, near his hometown.

His timing was fortunate. Newspapers were featuring reports on the laryngeal cancer that afflicted the Crown Prince of Germany. Morell Mackenzie, Jackson’s previous teacher, was a consultant on the case. The news informed the public about the relatively unknown specialty of laryngology, enhancing Jackson’s practice. Pittsburgh at the time was a grimy place, the air so thick with coal dust that the “sun was visible, on average, four days in a winter month.”1 Residents often kept lights burning indoors during the day.

From the beginning, Jackson saw many children from poor mining families with swollen, chronically infected tonsils. He described them as mouth breathers who slept poorly, were weary during school hours, and received poor grades. After removing their tonsils, their appetite, appearance, and school performance improved dramatically. Diphtheria was another plague for which Jackson did tracheostomies to bypass membrane-clogged throats. He performed esophagoscopies to retrieve swallowed objects such as coins, marbles, and pins, other childhood menaces. Finding Mackenzie’s esophagoscopes to be unwieldy, he devised new and better ones that included a light carrier. Without esophagoscopy, such patients often died since surgeons at the time were reluctant to enter the chest.

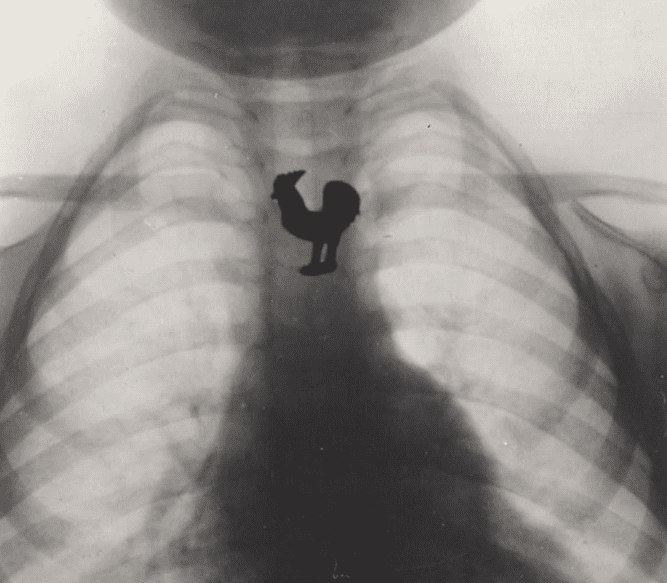

|

| X-ray by Chevalier Jackson of swallowed trinket embedded in candy. US Food and Drug Administration on Flickr. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Emaciated children with esophageal lye burns continued to crowd Jackson’s office. Lye was a common household item used to make soap. Jackson was so distressed at the number of tragedies that he initiated a crusade with the backing of the American Medical Association to have labels placed on containers holding poisonous substances. Industry and even merchants fought back, however, and his efforts did not succeed until 1927 when Congress finally passed the Federal Caustic Poison Law. Twenty-five years later, largely because of his efforts, lye had all but disappeared from store shelves, and lye burns were rare.2

Jackson’s practice grew rapidly but, sensitive to the poverty around him, he was careless in collecting fees, a lifelong habit. Many patients, in fact, came to him after being told by the referring physician that “he won’t charge you anything.” As a result, for many years he was constantly on the edge of penury, aggravated by the considerable money he spent on new instruments of his own design.

The time was ripe for another innovation: bronchoscopy. The first to perform an actual bronchoscopy was Gustav Killian, working in Freiburg, Germany. Killian taught himself the procedure by offering a small sum to a former hospital janitor to allow him, using local anesthesia, to pass an esophagoscope into the trachea rather than the esophagus. By 1898 he had reported four cases of foreign body extraction from the trachea, giving birth to the new specialty.

Chevalier Jackson took up bronchoscopy “with enthusiasm,” as he says in his memoir.3 Freely acknowledging Killian as the father of bronchoscopy, Jackson went on to develop more sophisticated instruments, designing them to accommodate tracheae from the size of infants’ to large adults’. He taught himself to be ambidextrous to increase his agility. Publications of his techniques generated invitations to demonstrate bronchoscopy to others, both in America and in Paris. He bypassed London, however; England’s antivivisection laws prohibited endoscopy on dogs, even anesthetized ones. He was rigorous about requiring training for the use of his instruments (to avoid injuries from improper use) and instructed his instrument maker never to sell an instrument unless the buyer could certify that he had completed a training course.

Jackson’s busy practice and long hours took their toll. In 1911, he began to cough blood and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Rest and proper diet were prescribed. He bought a small farmhouse out of town near the Ohio River where he spent the time writing a textbook. Entitled Peroral Endoscopy and Laryngeal Surgery, it was a 750-page, profusely illustrated work. The book was completed during a relapse of his disease and sold out almost immediately. He also published a shorter practical manual for students entering the field.

Academia began to seek him out. The Western Pennsylvania Medical College (later absorbed by the University of Pittsburgh) named him Professor of Laryngology. Then the New York Postgraduate Medical School elected him as Professor of Bronchoscopy. A resurgence of his tuberculosis, however, forced him back to his farmhouse for recuperation and finishing his text.

In 1916, he accepted the Chair of Laryngology at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, though a third and final relapse of tuberculosis interrupted him for a year. He used his appointment at the prestigious school to train additional specialists in the techniques he had largely invented. His expertise was in such demand, in fact, that he eventually held faculty positions at five medical schools in Philadelphia simultaneously. This violated exclusivity rules at the institutions, but trustees bent the regulations to keep him aboard. He created new, successful bronchoscopy departments in all five schools. He wrote more books and many medical articles, 238 of which were single-authored.4 He was an editor of the Archives of Otolaryngology, a founder of the American College of Surgeons, and penned an autobiography. One published tribute listed fifteen medals and honors that he received from five different countries.5 During his lifetime he extracted over 2000 foreign bodies from patients, largely children, all ensconced in the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.6 Only in later years did he use the bronchoscope to diagnose cancer and other disorders.

|

| Sunrise Mill, Jackson’s retirement home, now listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Montgomery County Planning Commission on Flickr. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 2.0. |

Beneath this busy and inventive exterior lay a humane, charitable, and very private soul that coexisted with an iron self-discipline. Chevalier Jackson maintained that ninety percent of his work with patients was gratis, and he spent much of his long life serving in city hospitals. His faculty appointments were usually without salary. He never patented his instruments, considering it immoral to profit from medical inventions.7 Though he had a kindly nature and was always available to his colleagues for help, they found him impossible to know in any intimate way. He seldom accepted social invitations, preferring his quiet home (a converted gristmill outside Philadelphia) and the company of his wife during rare leisure hours.

He saw virtue in self-discipline and self-denial. His workday began at 4:30 AM and ended at 9:00 at night. He was a vegetarian who ate sparingly, taking a “postage-sized” sandwich for lunch. He abstained from alcohol and tobacco and credited the abstentions for his steady hand in bronchoscopy.

In later years, he continued to write and pursued his talents as an artist and woodworker. He died at his converted mill, Sunrise Hill, near Philadelphia, at the age of ninety-three, completing an exemplary life as a medical pioneer and humanitarian.

References

- Chevalier Jackson, The Life of Chevalier Jackson: an autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1938), 96.

- Chevalier Jackson, “Federal Caustic Poison Law,” JAMA 150, No. 3 (1952): 158.

- Jackson, The Life of Chevalier Jackson, 116.

- Arthur D. Boyd, “Chevalier Jackson: The Father of American Bronchoesophagoscopy,” Ann Thorac Surg 57 (1994): 502-5.

- George M. Coates, “Chevalier Jackson, M.D., 1865-1958,” AMA Arch Otolaryng 69, No. 3 (1959): 372-4.

- Chevalier Jackson collection at the Mütter Museum website: https://muttermuseum.org/exhibitions/chevalier-jackson-collection.

- Boyd, “Chevalier Jackson.”

DR. J. GORDON FRIERSON received his B.A. at Yale University and his M.D. at Weill Cornell Medical College. He practiced internal medicine and infectious diseases in Oakland California and maintained part time clinical duties at the University of California San Francisco. In retirement he devotes time to the history of medicine. He is a member of the American Osler Society and the American Society for the History of Medicine, and has recently authored a history of the quarantine station in San Francisco Bay.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply