Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“There are always hysterical people undergoing extraordinary cures.”

– Robertson Davies, The Cunning Man

|

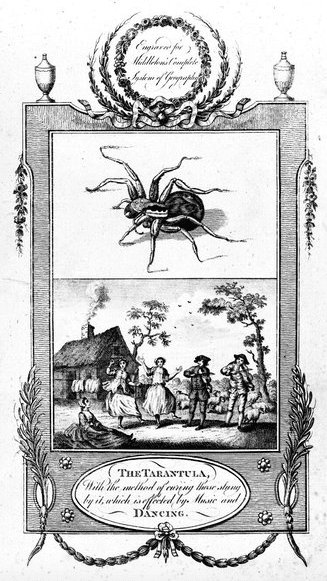

| Etching of people dancing the tarantella and playing music as an antidote to a tarantula bite. Wellcome Collection. Public domain. |

The industrial city of Taranto is in the “heel” of boot-shaped Italy. The Romans called the city Tarentum,1 and part of its historical importance comes from its name. Confusion has also arisen from that name’s overuse. A traditional folk dance, done by couples wearing local costumes as part of a courtship ritual, is called the tarantella. It originated in Taranto.

But another dance, also called the tarantella, is a “curative” dance done by individuals, groups, or entire villages. It is supposedly the result of a spider bite, with the spider being erroneously called a “tarantula.”2,3 The spider in question is actually a wolf spider, Lycosa tarantula, whose bite is not usually serious and never fatal.4 The supposedly bitten person dances wildly for hours, sometimes for days,5 if the right music (a “tarantella pizzica”) is played. This dancing is believed to save their lives by curing the envenoming via perspiration.

The belief in the spider bite’s effect and the need to dance afterward is known as “tarantism.” It was first described in the eleventh century,6 was seen often in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, peaked during in the seventeenth century, but persisted into the eighteenth.7 Similar phenomena were seen in Sicily, Spain, parts of Germany, Albania, and Ethiopia.8

Who were tarantism’s victims? They were people in the lower classes, usually harvesting in the summer. They were of all ages, and both men and women were affected, in variable ratios, depending on the region considered. The victim had no physical evidence of a bite and no one reported seeing a spider near them.9,10 Russell states that the victims were often “the hysterical, the melancholic, the depressed, the frustrated, the neurotic, the mentally deranged…those leading solitary lives, the bored…the malingerers, the rogues and the swindlers…”11

Symptoms would start from one hour to three days after the supposed bite. The victim would complain of headache, vertigo, anxiety, and fatigue. They would leap in the air, weep, seem to be mad, and have “grotesque convulsions.” The remedy for this disturbed (and disturbing) state was music, preferably provided by a group of musicians playing a flute, drums, fiddle, tambourine, or concertina.12 Once the music began, the victim danced wildly, tearing their clothes and making sexual gestures. After a variable time of dancing, they fell asleep and when awakening had no memory of the entire episode. In some victims, a similar episode would occur the next summer. There are reports of people having episodes for twenty consecutive summers.13

Medical interventions were tried. Unfortunately, bleeding and wine drinking were not helpful.14 A doctor in Naples in 1693 allowed himself to be bitten by two Taranto “tarantulas” in the presence of six witnesses. He did not develop the dancing illness.15

Most of the victims lived in misery and poverty. It has been questioned whether sunstroke, alone or combined with the drinking of massive quantities of wine during the harvest, could produce tarantism.16

Opinion today sees the etiology of this phenomenon as hysterical,17 a mass psychogenic illness18 resulting from emotional and social deprivation that produced an “unconscious explosion of forbidden sexual desires…[and] exhibitionistic gratification,”19 or “hysteria mixed with folklore, superstition, [and] local cultural influences.”20

We might ask if mass fainting at rock concerts is one of the current forms of tarantism.21

References

- Jeff Matthews. “Naples: life, death, and miracles. The tarantella,” 2012. naplesldm.com.

- Tarantella. Wikipedia.

- Paolo Toschi. “A question about the tarantella,” J International Folk Music Council, 2, 1950.

- Wolf Spider. Wikipedia.

- Tarantella. Wikipedia.

- Tarantism. Wikipedia.

- George Mora. “An historical and sociopsychiatric appraisal of tarantism and its importance in the tradition of psychotherapy of mental disorders,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 37(5), 1963.

- Jean Russell. “Tarantism,” Medical History, 23, 1979.

- Ibid.

- Mora, “Historical.”

- Russell, “Tarantism.”

- Ibid.

- Mora, “Historical.”

- Russell, “Tarantism.”

- Tarantism, Wikipedia.

- Russell, “Tarantism.”

- Tarantella. Wikipedia.

- Tarantism. Wikipedia.

- Mora, “Historical.”

- Russell. “Tarantism.

- Vittorio Sironi and Michele Riva. “Neurological implications and neuropsychological considerations on folk music and dance,” Prog Brain Res, 217, 2015.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply