Sama Alreddawi

Barry Meisenberg

Annapolis, Maryland, United States

“The Night Visitor”1

| …عَليـلُ الجِسـمِ مُمتَنِـعُ القِـيـامِ شَديدُ السُكرِ مِـن غَيـرِ المُـدامِ …وزَائِرَتـي كَـأَنَّ بِهـا حَـيـاءً فَلَيـسَ تَـزورُ إِلّا فـي الظَـلامِ بَذَلتُ لَها المَطـارِفَ وَالحَشايـا… فَعافَتهـا وَباتَـت فـي عِظامـي يَضيقُ الجِلدُ عَن نَفسـي وَعَنهـا… فَتوسِـعُـهُ بِـأَنـواعِ السِـقـامِ …إِذا مـا فارَقَتـنـي غَسَّلَتـنـي كَأَنّـا عاكِفـانِ عَلـى حَــرامِ كَأَنَّ الصُبـحَ يَطرُدُهـا فَتَجـري… مَدامِعُـهـا بِأَربَـعَـةٍ سِـجـامِ أُراقِبُ وَقتَها مِـن غَيـرِ شَـوقٍ… مُراقَبَـةَ المَشـوقِ المُستَـهـامِ وَيَصدُقُ وَعدُها وَالصِـدقُ …شَـرٌ إِذا أَلقاكَ فـي الكُـرَبِ العِظـامِ |

Sick of body, unable to rise up…

Vehemently intoxicated without wine …

And it is as though she who visits me were filled with modesty…

For she does not pay her visits save under cover of darkness …

I freely offered her my linen and my pillows…

But she refused them, and spent the night in my bones

My skin is too contracted to contain both my breath and her…

So she expands it with all sorts of sickness

When she leaves me, she washes me…

As though we had retired apart for some forbidden action …

It is as though the morning drives her away…

And her lacrimal ducts are flooded in their four channels

I watch for her time without desire…

Yet with the watchfulness of the eager lover

And she is ever faithful to her appointed time, but faithfulness is

an evil…

When it casts thee into grievous sufferings

For over a thousand years, the poetry of al Mutanabbi,2 one of the most prominent and influential Arab poets at the Abbasid court of Sayf al Dawla in Syria, has been used in Arabic literature as a reference and a proof of his wisdom, intelligence, pride, and insight.

Al Mutanabbi started writing poetry when he was nine. He wrote broadly on love, politics, battles, and mundane problems like his own medical concerns. He had an oeuvre of 300 folios of poetry when he died in 965 CE, the victim of a political assassination. His poetry has been translated into more than twenty languages worldwide and is accorded proverbial status in today’s Arab world for the wisdom and values it espouses.

As medical professionals, we read “The Night Visitor” with appreciation for al Mutanabbi’s more than 1,000-year-old comprehensive description of the common features of an acute illness characterized by malaise, delirium, bone aches, dehydration, profuse diaphoresis, and pleuritic dyspnea. Most striking is his lament of the most curious feature of all: the quotidian pattern of his misery. It is almost pathognomonic. It reminds us to ask for a travel history. Indeed, al Mutanabbi contracted his illness during a sojourn to Egypt, an area known to be endemic for malaria as far back as antiquity and to a lesser extent today.3

But his telling is not like that of a textbook, despite its completeness. Rather, he uses the poet’s tool of personification to imagine the illness as a mysterious, malevolent spirit who visits him bodily in the night and settles in his bones causing nocturnal misery before leaving him drenched the next morning from her overflowing lacrimal ducts. If we encountered a patient with such a story on hospital rounds today, we would surely diagnose hospital-acquired delirium and maybe order a psychiatry consult to help manage it. Having an imaginative patient equipped with the tools of a poet can represent challenges for a physician.

At a time when society struggles with yet another global pandemic, it is interesting to reflect upon how slowly knowledge of this endemic disease evolved over time. Malaria’s origins are ancient. The first description of the syndrome dates to 2700 BCE in ancient Chinese medical records.4 Over the millennia, malaria has disrupted civilizations, influenced the outcome of military campaigns, and killed important personages and commoners alike. Malaria has been attributed to many causes including supernatural forces; a notion disputed by Hippocrates who claimed it came from inhalation of bad air (a miasma, though he did not use that term) mostly found in swamps. Indeed, the word malaria is assembled from the words meaning “bad air.” Another term for malaria, “paludism,” derives from the Latin palus, meaning marsh. In the late nineteenth century, as bacteria became increasingly implicated in disease causation, it was assumed that malaria too was caused by a bacterium. This notion was disproved by the French parasitologist Charles Laveran, who identified amoeba-like parasites in the blood of patients with fatal cases of malaria in the 1880s. Though Laveran speculated on mosquitoes as the vector, that would be proven later by others. Laveran was awarded the Noble Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1907.4

More recently, the final mystery of malarial fever, the quotidian patterns, has begun to yield to the inquiries of scientific minds with modern molecular tools. It has been determined that malarial parasites have an intrinsic clock that allows them to synchronize with the hosts’ circadian rhythms and with each other, so that the timing of erythrocyte lysis that causes fever is coordinated.5

But we suspect al Mutanabbi would prefer his own explanation of nefarious goblins to those of modern scientists. Sometimes poetic terms serve better to describe the observed world than the mechanistic sciences of physiology and cell biology. Especially if your patient is equipped with the imagination of a poet.

|

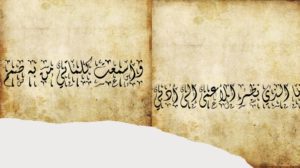

| “I am the one whose verses could be seen by the blind… and whose words were heard by the deaf.” Verse by Al Mutanabbi, translated by author. Created with Arabic Calligraphy Generator. |

References

- Browne EG. Arabian Medicine: The FitzPatrick Lectures Delivered at the College of Physicians in November 1919 and November 1920. Cambridge University Press; 2011. https://books.google.com/books?id=H_O1HiEHdZsC.

- Üyesi Ö, Üniversitesi K, Fakültesi FE, Dili A, Dalı A. al-Mutanabbī’s Panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla (Sayfiyyāt). 2020;7(2):497-518. doi:10.33460/beuifd.810283.

- Shibl A, Senok A, Memish Z. Infectious diseases in the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(11):1068-1080. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12010.

- Talapko J, Škrlec I, Alebić T, Jukić M, Včev A. Malaria: The past and the present. Microorganisms. 2019;7(6). doi:10.3390/microorganisms7060179.

- Rijo-ferreira F, Acosta-rodriguez VA, Abel JH, et al. The malaria parasite has an intrinsic clock. 2020;368(6492):746-753. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3708087.

DR. SAMA ALREDDAWI is a clinical assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She works as the associate program director of internal medicine residency program at Luminis Health, Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, MD where she served prior as a chief medical resident. She graduated medical school from Damascus University, Syria and finished her internal medicine residency at Medstar Health, Baltimore, MD along with Global Health Track Residency at Medstar Georgetown University in Washington, DC. She has a focus in global health and an interest in arts and humanities.

BARRY MEISENBERG, M.D., is a hematologist-oncologist and Chair of Medicine for Luminis Health, in Maryland. He has held leadership positions in both academic and community cancer centers. Ex-officio, he organizes and moderates a humanities-focused program for medical staff and trainees called “Diastole Hour.” Named for the relaxation phase of the heart, Diastole Hour uses fiction and poetry by or about physicians, visual art, and medical history to generate reflection about what it means to be a physician or a patient. Diastole Hour’s goal is to re-awaken the joy and delight of medicine, for we shouldn’t spend our whole lives in systole.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply