JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

His grace, his God-knows-what: for Cupid’s cup

With the first draught intoxicates apace,

A quintessential laudanum or ‘black drop,’

This makes one drunk at once, …

Byron’s Don Juan (1823)

|

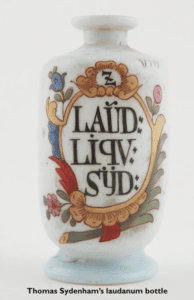

| Figure 1. Glass bottle inscribed “Laud:Liqv:Syd” (Sydenham’s laudanum) |

|

| Figure 2. Kendal “Black Drop” |

The opium or breadseed poppy (Papaver somniferum) was native to Turkey and was known to ancient Assyrian herbalists. Theophrastus described it in the third century BC, and in the first century AD, the Greek physician Dioscorides described opium in his treatise De materia medica. The use of opium spread slowly from Mesopotamia and Greece and reached China c. 650 AD where opium smoking became common practice.

Shakespeare was familiar with its properties when in Othello (1622) he wrote:

Not Poppy, nor Mandragora,

Nor all the drousie sirrops of the world,

Shall euer medicine thee to that sweete sleepe.

Paracelsus used opiates in his preparation of laudanum, a name used at the beginning of the seventeenth century for various preparations used to relieve pain, in which opium was the active ingredient. Laudanum, recommended in the 1660s by Thomas Sydenham, (Fig 1) was an alcoholic tincture of opium (Fig 2) used in a wide variety of aches and pains, rheumatism, fibrositis, and headaches, as well as in feverish maladies.

Even the briefest perusal of nineteenth century habits shows that laudanum was commonly used and easily available without medical prescription. Laudanum appears to have been the predecessor of aspirin and later paracetamol, used frequently and with few ill effects in the majority. Presumably, in most instances, only a short course of a few days was employed; this may explain why habituation and addiction were so rarely reported.

One of the most popular remedies was the Kendal Black Drop, made from opium and flavored with sugar and spices. It was also known as Lancaster and Armstrong’s Black Drop, and Quaker’s or Toustall’s Black Drop after Dr. Toustall of Durham who was said to have invented it. Another popular recipe for pain control was Syrup of Poppies; and Paregoric was a camphorated extract of opium used for bowel disorders.

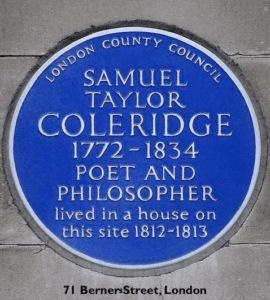

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

|

| Figure 3. S.T. Coleridge. From Richard Holmes’s Coleridge: Early Visions, 1989.1 |

Amongst those familiar with the Kendal Black Drop was the famous poet and writer Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) (Figs 3 & 4). He was the son of the vicar of Ottery St. Mary, Devon and headmaster of Henry VIII’s Free Grammar School. He had a classical start to life, being educated at Christ’s Hospital and Jesus College, Cambridge.

A complicated, luminous intellectual, his work bears the inescapable glow of the authentic visionary.1 But he also valued more commonplace domestic duties, gardening, fell walking, and natural history. In 1794 with the poet laureate Robert Southey and Joseph Hucks, a Cambridge friend and travel-writer, he decided to form a small brotherhood of “pantisocrats” designed to eliminate hatred and materialism prevalent in society. This was to be a lifestyle based on tolerance, equality, abandonment of personal property, and participatory government. This admirable if typically naïve ideology came to naught. But in 1798 he spent a fruitful year with Wordsworth at Nether Stowey in the Quantocks in Somerset, in which they “together wantoned in wild Poesy.” Their deep friendship resulted in their acclaimed Lyrical Ballads that included Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, his Frost at Midnight, and Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey. Thus began the English Romanticism. The Poetry Foundation provides an excellent essay on his poetry.2

Coleridge records increasing debility, rheumatic pain, and illness for several years and he started to take the Kendal Black Drop whilst in Greta Hall, Keswick in 1803. An ode entitled Dejection written on the 4th of April 1802 illustrates his morbid depression and grief:

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word, or sigh, or tear—

He described himself suffering from:

A supposed rheumatic affection, attended with swellings in my knees and palpitation of the heart and pains all over me, by which I had been bed-ridden for nearly six months. I had always a fondness … for dabbling in medical writings; and in one of these reviews I met a case which I fancied very like my own, in which a cure had been effected by the Kendal Black Drop. In an evil hour I procured it: it worked miracles–the swellings disappeared, the pains vanished. I was all alive, and all around me being as ignorant as myself, nothing could exceed my triumph. … Alas! it is with a bitter smile, a laugh of gall and bitterness, that I recall this period of unsuspecting delusion, and how I first became aware of the Maelstrom, the fatal whirlpool to which I was drawing, just when the current was beyond my strength to stem.3

Subsequent years were beset with fluctuating spells of melancholy, rheumatism, bowel pains, infirmity, and increasing habituation to opiates and alcohol. He continued to write in his lucid intervals, but often failed to complete his work. Eventually his labile marriage to Sara Fricker ended and he fell in love with Sara (Asra) Hutchinson, sister of Wordsworth’s wife Mary. His erratic behavior and deceptions driven by laudanum caused him and Wordsworth to drift apart. He continued to write, travel, and socialize despite his incessant complaints.

|

| Figure 4. S.T. Coleridge Blue plaque at 71 Berners St. (his home 1812–13) |

Coleridge was strongly supported and encouraged by distinguished friends, the poets Wordsworth and Southey and by Cottle, Charles Lamb, Lord Byron, and Josiah and Thomas Wedgwood. He was a man of great charm, a wonderfully well-informed conversationalist, whose imaginative if naïve visions and writings of life attracted the highest praise and indulgence from everyone he knew. In 1808 he lived in London at his old free quarters in the Courier office and gave sixteen lectures on poetry and the fine arts, the London Institution lectures of 1808, and many lectures elsewhere, notably on philosophy, literature, and Shakespeare.4

When the promises of Morpheus, the god of dreams, and his son Hypnos, the god of sleep in Greek mythology, failed to provide adequate solace, he changed from the Kendal Black Drop to liquid preparations of laudanum/opium, and claret, both of which he consumed in vast volumes. By 1814, Cottle said in his Recollections that S.T.C. had been long, very long, in the habit of taking from two quarts of laudanum a week to a pint a day, and on one occasion he had been known to take in the twenty-four hours a whole quart of laudanum.

(The recipe was: Take ½ lb. of opium, sliced; 3 pints of good verjuice; 1 ½ oz of nutmeg; ½ oz of saffron; boil them to proper thickness, then add ½ lb of sugar and two spoonfuls of yeast. Set the whole in a warm place, near the fire, for 6 or 8 weeks, then place it in the open air until becomes of the consistence of a syrup; lastly, decant, filter and bottle it up, adding a little sugar to each bottle. These ingredients ought to yield, when properly made, about 2 pints of the strained liquor.)

A youthful pharmacist, Friedrich Serturner (1783–1841), in 1804 isolated morphine as the most active ingredient of opium; he warned of its addictive potential. Diacetylmorphine (heroin), synthesized in 1874 by the chemist C.R. Alder Wright, proved even more potent and addictive than morphine.

Opium was consuming Coleridge. He had little money and no means of support for his children’s education. Before departing for Greece, Lord Byron came to his assistance with a loan of a hundred pounds and words of counsel and encouragement. He understood The Black Drop, mentioned in his Don Juan, cited above.

Byron introduced Coleridge to Mr. Murray, who published incomplete versions of Christabel, Kubla Khan (subtitled Vision in a dream) and The Pains of Sleep, for eighty guineas, which he promptly gave to the Morgan family who had housed and fed him for five years.

From his own account, these visionary ideas were owing to an anodyne—clearly opium. In The Pains of Sleep, Coleridge tells us how deeply he felt and suffered, and was prey to: “Fantastic passions! maddening brawl! / And shame and terror over all!” His guilt and peccadilloes he disclosed in a letter to his friend John Morgan: “I have in this one dirty business of Laudanum an hundred times deceived, tricked, nay, actually & consciously LIED – And yet all these vices are so opposite to my nature…”

He sought to make amends. In April 1816 he visited the house of James Gillman, a Highgate surgeon, and was housed as an inmate to help cure his opium addiction. Gillman achieved some measure of control if not cure of his habit and provided a home for the rest of his life.5,6 From 1818 to his death, he was devoted mainly to metaphysics and theology. He briefly returned to better health and renewed his writing with Biographia Literaria, and in 1825 his Aids to reflection in the formation of a manly character….

In 1828 he accompanied Wordsworth and his daughter on a tour of the Rhine, but he never shed his burden of opium. Three years later he wrote that for eighteen months past his life had been “one chain of severe sicknesses, brief and imperfect convalescences, and capricious relapses.” Thereafter, he was confined to his sickroom. His faculties, however, remained unclouded. He died on 24 July 1834. At his request an autopsy was carried out (reported by Lucy E. Watson in Coleridge at Highgate) that showed “acute dilatation of his heart.”

His own self-pitying epitaph is touching:

Here lies a Poet; or what once was he;

Pray, gentle Reader, pray for S.T.C.

That he who three score years, with toilsome Breath,

Found Death in Life, may now find Life in Death

Coleridge, though plainly introspective, self-absorbed, and endlessly occupied by fears and illness, was a matchless letter writer, journalist, critic, and “—that much disputed word—a metaphysician.”1 His poetry and writings on philosophical and theological subjects, although discursive and fragmentary, were brilliant aperçus, fervidly eloquent, and reflective. He repeatedly expressed remorse at his opium habit, and realized its addictive and destructive powers.1,5 He was not alone; Shelley and Byron also took laudanum. Thomas De Quincey was similarly productive in his bizarre dreams and visionary writings, most famously his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821). This was an autobiographical account of his laudanum addiction and its effect on his life: “If opium-eating be a sensual pleasure…it is no less true that I have struggled against this fascinating enthralment with a religious zeal.” He also wrote a critical essay, “Coleridge and Opium-Eating.”

References

- Holmes Richard. Coleridge: Early Visions. London. Hodder & Stoughton, 1989.

- Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/samuel-taylor-coleridge

- Traill HD. English men of letters: Coleridge. Macmillan and Co. London, London, 1884

- Beer J. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1772–1834), poet, critic, and philosopher. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 3 Apr. 2022, from https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-5888.

- Lefebure Molly. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A bondage of opium, London, Gollancz, 1974.

- Gillman J. The life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. London 1838. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/8957/8957-h/8957-h.htm#section4

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Spring 2022 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply