JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

William Wordsworth (1770–1850) was born in Cockermouth, Cumberland, on April 7, 1770. He was the totemic father of the Lakeland poets, who extolled the relation between man and the natural world: a wedding between nature and the human mind that to him symbolized the mind of God. A prolific writer of letters, essays, and poetry, he was elected poet laureate.

Eye disease

It is often reported that from 1805 until his death Wordsworth experienced recurring episodes of the infectious disease trachoma, which causes painful inflammation of the eyelids and conjunctiva and can cause blindness. At times this was so severe that it restricted both his writing and reading. His daughter Dora and many others referred to him as “the blind poet.”1,2 Considering his huge output of written works, this might occasion surprise.

His own account in a comment on his poem A little Onward lend thy guiding hand [XXIII] is worth quoting:

The complaint in my eyes which gave occasion to this address to my daughter first showed itself as a consequence of inflammation, caught at the top of Kirkstone, [sic] when I was over-heated by having carried up the ascent my eldest son, a lusty infant. Frequently has the disease recurred since, leaving the eyes in a state which has often prevented my reading for months, and makes me at this day incapable of bearing without injury any strong light by day or night. My acquaintance with books has therefore been far short of my wishes, and on this account, to acknowledge the services daily and hourly done me by my family and friends, this note is written.

Because trachoma is typically a disease of overcrowding and poverty, it is more likely that he caught the disease in his frequent travels to London and Europe than in the solitary summit of Kirkstone. Indeed, in Wordsworth’s poem The Pass of Kirkstone (1817) he records:

Where, save the rugged road, we find

No appanage* of human kind,

Nor hint of man;

The Blind Beggar of Book VII of The Prelude may be based on his experiences. Stephen Gill’s biographical note records that Wordsworth’s only serious medical worry was for his eyes, which frequently became so inflamed that he feared he would go blind. In later life he regularly wore a shade or tinted glasses.3

In a letter to Professor Hamilton, Observatory, Dublin on July 24, 1820, Wordsworth said:

I have been very long in your debt. An inflammation in my eyes cut me off from writing and reading, so that I deem it still prudent to employ an Amanuensis;

This coincides with a further attack of symptoms in 1820 when he feared he might be going blind, like his hero Milton. From this time the attacks became more frequent, and he started to wear a green eyeshade to alleviate his symptoms.

Writing to C. Huntly Gordon, Esq. on July 29, 1829 he noted his diseased eyes had cut him off so much from reading. And to the celebrated writer Charles Lamb on January 10, 1830, after praising his play, he remarks:

On account of the smallness of the print, deferred doing so till longer days would allow me to read without candle-light, which I have long since given up. But, alas! when the days lengthened, my eyesight departed, and for many months I could not read three minutes at a time. You will be sorry to hear that this infirmity still hangs about me, and almost cuts me off from reading altogether.

Described by his daughter Dora as a “blind man,” she related how he sought repeated medical advice to manage symptoms, which often confined him to darkened rooms for days. He was also advised that the writing of poetry could worsen the condition. When he had trouble seeing, his sister Dorothy would read to him.4,5 He wrote to a friend that “it made me so dependent on others, abridges my enjoyments by cutting me off from the power of reading and causes me to lose a great deal of time.” He also said at times his work was so ill-penned and blurred that it was useless “to all but myself.” This must have reminded him of his hero, the poet John Milton, who became totally blind. In 1827, Frederic Reynolds, editor of The Keepsake, gave Wordsworth a blue stone to apply to William’s eyes, which appeared to provide brief relief.

Portraits of Wordsworth

Sixty-three portraits are recorded.6 He was recovering from an episode of recent eye inflammation when the artist Margaret Gillies painted his portrait; a print taken in 1839 appears in the National Portrait Gallery. Interestingly, even on magnification, this print shows no visible evidence of inflammation or morphological signs in the eyelids, pupils, cornea, or sclerae.

The portrait of William Wordsworth by Henry William Pickersgill in 1833 (Fig 1) and a sketch by Benjamin Robert Haydon around 1820 likewise show no obvious external signs of ocular disease.

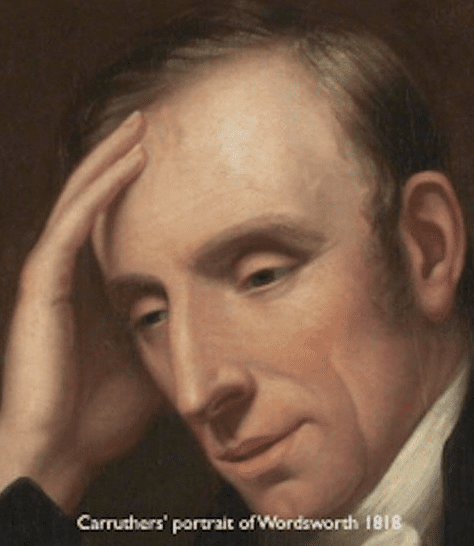

In preparing her book The Later Wordsworth, Edith C. Batho consulted an ophthalmologist on the subject, giving him several portraits as evidence. The Edward Nash† and Carruthers drawings6 in particular suggested trachoma. She reported the ophthalmologist’s conclusions:

However, reservations were expressed:

The Carruthers portrait of 1828 is shown (Fig 4) with heavy upper eyelids but no obvious signs of blepharitis or conjunctivitis. The 1807 drawing by Henry Eldridge shows heavy lids long before the onset of symptoms, i.e., they were constitutional.

The St. John’s College Cambridge records gives a full account of Wordsworth and his portraits7 with no mention of ocular symptoms or signs, which were intermittent and more troublesome in later years later.8

Trachoma

Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. The prevalence peaks in pre-school children and declines to low levels in adulthood. The recurrent conjunctival inflammation causes scar tissue of the eyelids that develops in later life, usually in the third decade, causing entropion and corneal damage.9

Transmission is probably promoted by interpersonal contact in unhygienic living conditions, flies, and poverty and squalor. It is prevalent in Sudan, Ethiopia, the Middle East, India, and parts of Asia and South America. It is rare in Great Britain today, but in Wordsworth’s time trachoma was rife, imported by soldiers who had contracted it, probably in Egypt, during the Napoleonic wars. It led to the founding of Moorfields Eye Hospital, the first hospital in the world devoted to the treatment of eye disease, in October 1804. The hospital moved in 1822 to Lower Moorfields, close to what is now Liverpool Street station.

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (1770–1850) was born in Cockermouth, Cumberland, on April 7, 1770, the second of the five children of John Wordsworth and his wife, Ann née Cookson. His schooling started in Cockermouth, then at the Hawkshead Grammar School, after which he studied at St John’s College, Cambridge graduating without great distinction in January 1791. He traveled widely through England and Europe and he supported the French revolution. He formed close friendships and collaborated with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and Thomas De Quincy and many other influential literary figures. Wordsworth married Mary Hutchinson on October 2, 1802 and with his devoted and inseparable sister Dorothy they moved to Dove Cottage, Grasmere; in 1808 they lived at Allan Bank, and from 1813 at Rydal Mount. All are idyllic sites of unmatched rural beauty amongst placid lakes and majestic mountains.

His early collaboration with Coleridge resulted in their widely acclaimed Lyrical Ballads that included Wordsworth’s poems Tintern Abbey, Expostulation and Reply, and The Tables Turned. When their relationship soured, the second edition of 1800 included works by Wordsworth alone. After the age of forty he was less productive, but he wrote The Solitary Reaper, Resolution and Independence, and Ode: Intimations of Immortality, perhaps the greatest of his lyrics. In 1843 he was made poet laureate. In addition to poetry he wrote prose (with great difficulty, he said), many letters and essays airing his polemical views of politics and religion, as well as his travel book: A Guide through the District of the Lakes.

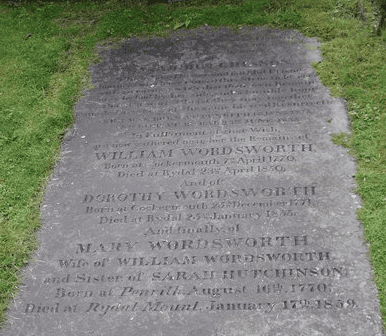

In old age Wordsworth remained physically vigorous; he climbed Helvellyn for when he was seventy. Having suffered pleurisy allegedly from recklessly walking out in frosty weather, he died aged eighty, at Rydal Mount on 23 April 1850. He was buried in the tranquil little churchyard at St Oswald’s, Grasmere. His sister Dorothy died in 1855, and wife Mary died on in January 1859. They were buried with him (Fig 5). The Prelude, an autobiographical poem was published three months after his death.

It is plain that Wordsworth suffered from intermittent and at times disabling eye symptoms, with inflammation, photophobia, and difficulty in reading and writing. Symptoms were intermittent, witness the letter of December 29, 1834 from his nephew Chris to William’s brother: “My Uncle’s eyes are…much better, indeed they would be quite well, if he did not write verses…”10 In 1840, his wife Mary wrote that “tho’ he labours in constant fear of his eyes and complains of discomfort from them – yet in reality he has had very little suffering.”11 Despite a current lack of conclusive evidence, trachoma seems the likeliest explanation. Though now rare in the UK, it was common in his time owing to spread from soldiers returning from the Napoleonic wars in which it was of almost epidemic proportions. Wordsworth’s prolific writings of prose, letters, and poetry and the reading undertaken in his correspondence show that his visual acuity and corneas cannot have been permanently or seriously impaired. The frequent assertions of “Wordsworth the blind poet” are unjustified.

End notes

*appanage [archaic] land, means of subsistence or provision.

† In a private collection, Hampshire, drawn for Southey but probably based on Meyer’s engraving after Carruthers.6

Image captions

- Henry William Pickersgill’s portrait of William Wordsworth, 1833

- Trachoma

- Trachoma not definitely proved

- Carruthers portrait etching (1828). O’Donoghue 1908-25 / Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum.

- Graves of William, Mary, & Dorothy Wordsworth at Grasmere. JohnArmagh on Wikimedia, August 20, 2007. Public domain.

References

- Bewell A. Wordsworth and the Enlightenment. Nature, Man, and Society. Yale University Press: 1989.

- Tilley H. Blindness and Writing: From Wordsworth to Gissing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Stephen Gill. Wordsworth, William (1770–1850). In: Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2010.

- Hunter Davies. William Wordsworth: A Biography. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Published: 1980.

- Grosart AB. The Prose of William Wordsworth – Volume III. London: Edward Moxon, Son, And Co; 1876. New York: AMS Press, 1967. https://www.poetrysoup.com/short_stories/prose_of_william_wordsworth_iii.aspx#letter1

- Blanshard France. Portraits of Wordsworth. London: George Allen & Unwin 1959.

- The St John’s College Records (Animae Naturaliter Johnianae) The Eagle 1950;54, No 237 pp.113-143.

- Harper GM. William Wordsworth: His Life, Works, and Influence New York. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916.

- Burton MJ. Trachoma: an overview. British Medical Bulletin 2007; 84: 99–116.

- Tilley H. Wordsworth’s Glasses: The Materiality of Blindness in the Romantic Vision. In Illustrations, Optics and Objects in Nineteenth-Century Literary and Visual Cultures, ed. Luisa Calè and Patrizia Di Bello (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2010), 51.

- Harper P. William Wordsworth’s glasses and the lifelong struggle with his eyesight. Museum Crush: https://museumcrush.org/william-wordsworths-glasses-and-the-lifelong-struggle-with-his-eyesight/

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022

Leave a Reply