Henri Colt

Laguna Beach, California, United States

|

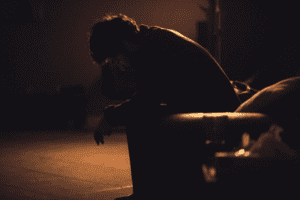

| Man sitting. Photo by Gadiel Lazcano on Unsplash. This short story is a work of fiction. |

Translation: “What an artist the world is losing with me!”

— cited by Suctonius, The Twelve Caesars, Nero 49; Loeb ed., 2:177

Michael had jet black hair and sorrowful brown eyes that sparkled when he smiled, which was often. Sprawled on his lounge chair every Saturday, he soaked up the sun while neighborhood girls lingered, serving iced tea and lemonade. Life seemed simply marvelous.

He was not stunning, but he was good-looking in a disheveled, youthful, rebellious sort of way. Teenagers gathered around him, sitting on the grass, playing badminton, or gleefully tossing Frisbees back and forth in the backyard. Most of all, they listened amorously to his stories of adventurous treks in Asia or climbing steep rock walls in Yosemite. Late that spring, just two weeks before the start of summer vacation, he graduated at the top of his class from one of the best medical schools in the country.

I had known Michael since I was nine. We grew up together, although he was two years older than me. Our parents were friends, and like him, I became an Eagle Scout, president of my high school class, and wore a leather-handled Ka-bar US Marine Corps knife on my shin when I went camping. I applied to medical school and stayed local, so I hung around him as much as possible. He introduced me to ancient Greek philosophy and French theater, and tutored me in computer sciences. I did more than look up to him; I worshipped him because he was good at everything. He even played harmonica and lead guitar to my piano, vocalizing harmonies that outmatched my wretched voice singing the blues in coffee shops.

Once, we were sitting in the living room of his apartment overlooking the park in our well-to-do Southern California neighborhood. We were just a few blocks from his parents’ home. Souvenirs from his travels were scattered among ornately framed contemporary lithographs and a collection of books stacked on wooden shelves. I remember Jamie Cullum’s soft jazz playing in the background.

I set my third bottle of beer on the coffee table.

“So,” I said. “Graduation is coming up. What’s going to be your specialty?”

“Psychiatry.” He spoke as if there were no alternatives, as if no other specialties existed.

“Sounds boring,” I said.

He rattled the ice in his Scotch before answering. “I have questions I need answers to.”

“Psychiatry, jeez,” I said. “You’re working through endless analysis, rehashing ad-infinitum the old Jung versus Freud and Lacan stuff or—”

“You have it all wrong.” Michael interrupted.

“Or,” I insisted on finishing my sentence, “using mind-altering drugs to interfere with neurochemical pathways most people know nothing about.”

A silence lingered. Michael knew I wanted to become a surgeon and that anything but instant gratification was foreign to me. He lowered his eyes. He was always quiet when he pondered his way to a convincing argument.

“Mind and body work together,” he said softly, “but while the surgical repair of an artery or the artful removal of a gallbladder requires technical skill, good judgment, and able decision making, it can’t compare to the personal creativity needed to doctor the perplexing and contradictory environments of the human psyche.”

“What do you mean?” I said.

Michael set his glass on the table. “I mean that when people consult a psychiatrist, they are not only asking to feel good or to be healed, they are asking to fit into society.”

“Huh?”

“They want to know where they stand regarding norms on society’s emotional and behavioral bell curves. They don’t say so directly, but they want to know if it’s okay for them to be the way they are, or if they need to change…to reconsider their life history.”

He paused as I weighed his words. I gazed past the open balcony door to examine the Mexican-tiled rooftops of his parents’ hacienda home less than a block away. I stood to feel a warm breeze floating up through the eucalyptus trees.

“Of course, there is pathology,” he continued. “DSM-classified mental illness, I mean. But I’m not talking about that. I mean that everyone carries pathological traits within them just waiting to be released. Most of the time, people ignore them. They become delusional about their own existence. Other times, those traits become manifest. Observers don’t realize it unless behaviors are grossly outside the norm. What I am saying is that in all sense, most of us seem normal.”

Thinking back, I can’t help but conclude he was telling me something. He was reaching out in some odd let me guide others so that I could guide myself way. I should have probed his feelings. Instead, I challenged him.

“So, Michael, you’re saying that everyone’s living a lie.”

“It’s Hollywood,” he retorted.

“That’s hard to believe,” I said. “I mean, it seems to me most people are happy. They go to work, school, and take vacations. There are couples everywhere.” I walked to the bookshelf and picked up a black Akuaba fertility doll he had found in Ghana during one of his trips. Carved from ebony wood, its flat, oval head and annulated neck were attached to a short, rectangular body. “People get married,” I said. “They have kids. They raise families. In the end, they retire to a golf community.”

I presumed he would laugh at my pragmatism, but his face turned somber.

“It’s all a lie,” he said. He averted my gaze to look past me, outwards beyond the balcony. After another silence, he rose from the couch. There were fresh coffee stains on the armrest where he had been sitting. He placed his hands on his hips and arched his back to stretch.

“Where is it, though?” he said. “Where is the lie?”

His questions sounded rhetorical. He walked past me to shut the balcony door, then turned. He passed his hands through his hair and clasped them behind his neck. His elbows pointed forward when he faced me. I was surprised to hear him raise his voice.

“Is it a lie if my life is governed by a false self, even if I don’t realize the false self is in command?” he said. “Is it wrong for me to become true to my Buddha nature, even if I’m not certain what that is?”

“Jeez, Michael, you ask yourself too many questions. Everything comes to you too easily. You enjoy life. Why ask questions to which there are no answers?”

Michael put his hands in his pockets and leaned his body into the corner of the room. “Well, my friend, if you had a choice – if you could have chosen your mother and father, would you have changed anything?”

I was the first person Michael’s parents called on Monday, that third week in May. After his graduation celebrations, Michael went to his parents’ house and hanged himself from a wooden beam in their living room. When I rushed through their door, I saw his body dangling lifelessly from the ceiling, casting alternating shadows of different intensities on the marble floor; shadows that changed with the position of the Pacific sunset fluttering on the horizon.

HENRI COLT is a physician-writer, medical ethicist, and philosophical counselor whose short stories have appeared in Rock and Ice Magazine, Hektoen International, CafeLit, and elsewhere. In addition to writing several medical textbooks, he is the author of Amedeo Modigliani: Drunken Bohemian or Contagious Consumptive, and writer/editor of The Picture of Health: Medical Ethics and the Movies (Oxford University Press). He is Professor Emeritus, University of California.

Winter 2022 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply