Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“You sing ‘My country ’tis of thee’ while they walk all over you.”

— The patient, Pressure Point

|

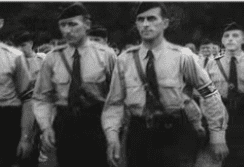

| German American Bund rally (1938 or 1939). From “Battle of the United States”, produced by Army Information Branch, Army Pictorial Service, Air Forces, and Navy Department in cooperation with all united nations, 1944. Accessed at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives & Records Administration, via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Pressure Point (1962) is a “doctor movie” that is “all but unknown to the general public.”1 This is unfortunate, since it contains important messages as well as some splendid acting. The story is told as a flashback, when an unnamed senior hospital psychiatrist (played by Sidney Poitier) describes to a young colleague the treatment of a difficult patient (played by Bobby Darin) whom he was assigned twenty years earlier in 1942.

The psychiatrist was working in a federal penitentiary. He received a patient, a young white American Nazi, who had been convicted of sedition and starting a riot and was serving a three-year prison term. The filmmakers wanted an “all-American” boy (that is, Bobby Darin) to play this part.2 The patient laughs upon meeting the psychiatrist and says, “I don’t care what you think. You’re a Negro.” He also says, “Jews put that cripple [President Franklin D. Roosevelt] in the White House,” and that Jews are “more dangerous [than Blacks] because they pass for white and they’re smart.” The psychiatrist realizes that he is dealing with a problematic individual.

He learns about the patient’s terrible but not unique childhood: an alcoholic, abusive father who brings barflies home and flaunts them before his wife, who is “weak,” helpless, and dependent. The patient left home at age fifteen and took jobs that “weren’t fit for a white man.” He is not very disturbed by his imprisonment because Adolf Hitler had written Mein Kampf while in prison. He describes how he humiliated and terrorized a bar-owner and a female employee.

(It is not clear if he raped her.) The doctor realizes that he has worked with murderers who were “more human” than this patient. He wants to let some other doctor have the case, but his supervisor insists that he continue with the patient. The patient expounds on more of his political ideas: People need someone to hate. We unite against Jews and Blacks. The enemy eventually fights back, and this creates more interest in our cause, as well as more members and donations. The average man wants a leader. We can’t be stopped. We have syndicated columnists and “Detroit manufacturers” with us. We have camps where kids read Mein Kampf.

He describes being invited, during the Depression, to call on a young woman, but her father would not let him in. The family was Jewish. It was then that he joined the pro-Nazi German-American bund. The doctor tells him that he has a “storm trooper mentality,” which he takes as a compliment. He then replies that America is founded on a lie: “All men are created equal.” If that were true, why do Blacks have inferior schools and live in Harlem in ghettos?

Finally, he has served his sentence and may leave prison if the psychiatrists think he is ready. They all do, save the doctor who is treating him. In principle, this means he cannot be released, but he appeals to the senior doctors, who override his treating doctor’s concern, namely that he is a psychopath unready to be returned to society. His doctor’s concern is overruled.

The patient rejoices and asks his doctor, “The people you work with, who did they believe? The big Black boy who’s supposed to be running this place, or the white Christian American?” The doctor replies, “I wanted to kill you, and I wanted to help you. You’re gonna lose. There’s something in this country that will not let you and your bunch succeed.” The flashback ends, and the now senior psychiatrist informs his young colleague that ten years after his release, the patient beat an old man to death for no apparent reason.

The doctor-patient dialogue in this film has been called “a two-man show that plays out like a powerful tennis match.”3 The film lost money. Peter Dans does not mention it in his nearly 400-page Doctors in the Movies. Glenn Flores4 includes it in his top-ten films “most-useful in medical education.” The patient’s dialogue reminds the audience (the psychiatrist needs no reminding) of the condition and treatment of Black people in America. What he described in 1942 was not that different in 1962. The civil rights movement was gaining national attention in the 1960s, and Sidney Poitier’s defense of and hopes for America were part of the civil rights agenda. He was a generous donor of time and money to the cause of civil rights.

Bobby Darin, in an interview5 after the film was released said, “Do not fall asleep to the hazards of fascism…Be able to recognize the individual for what he is, under the guise of whatever he is preaching.”

References

- Frank Calvillo. “Pressure Point offers stirring social commentary and powerhouse acting.” Cinapse.co, 2016.

- Bobby Darin. “Why I played a film bigot,” Ebony, 18(1), 45-50, Nov. 1962.

- Calvillo, “Pressure point.”

- Glenn Flores. “Doctors in the Movies,” Arch Dis Child, 89(12), 1084-1088, 2005.

- Darin, “Bigot.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Winter 2022 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply