Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

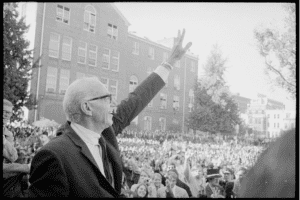

| Spock Behind G.W. Library. Photo by Warren K. Leffler, October 15, 1969. U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. No known restrictions on publication. |

“Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale.”1

— Rudolf Virchow, M.D. (1821-1902)

“It took me until my sixties to realize that politics was a part of pediatrics.”2

— Benjamin Spock, M.D.

Benjamin McLane Spock (1903-1998) was an American pediatrician and author of Baby and Child Care, which has sold over fifty million copies worldwide since 1946. During the last thirty years of his long life, he devoted most of his energies to political causes.

He was born into an affluent Connecticut family and was part of the US rowing team that won a gold medal in the 1924 Paris Olympics. He earned his M.D. degree from the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1929, graduating first in his class. He went on to complete residencies in pediatrics and psychiatry. During World War II he served as a psychiatrist in the US Navy Reserve and prepared the manuscript for his best-selling book. Over his lifetime he wrote fourteen books, mainly about childhood and adolescence, and a few on political themes.

In 1962 he joined SANE (the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy) when the US resumed testing of nuclear weapons.3 He understood that the arms race between the US and the Soviet Union was continuing to escalate, without a defined endpoint in sight. He became co-chair of SANE in 1963. In the 1964 presidential election, he supported the candidacy of Lyndon Johnson, who promised to “bring American boys” home from the war in Vietnam. Once elected, however, Johnson massively increased the American military presence in Vietnam. Dr. Spock began to speak, write, march, and travel across the US to demonstrate for peace. He encouraged Martin Luther King to take part in the criticism of American involvement in the Vietnam War. King, at his first anti-war demonstration in March 1967, marched alongside Spock.4

As the war escalated, the tactics of the “New Left,” of which Spock was a de facto member, became more focused. Spock wrote that he had never been a pacifist, supported World War II, NATO, and the US role in the Korean Conflict.5 Vietnam was different. The American government was closely watching anti-war demonstrations.

|

| Young man wearing helmet with peace sign burns his draft card at an anti-draft demonstration at the Selective Service System headquarters. Photograph taken either by Marion S. Trisoko or Thomas J. O’Halloran, March 19, 1970. U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. No known restrictions on publication. |

In mid-October 1967, the anti-war movement published “A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority,” followed by a “Stop the Draft” week. On October 16, the Reverend William Sloane Coffin and graduate student Michael Ferber held a church service in Boston where young men turned in or burned their draft cards, that is, the proof of having registered to be called upon for military service. Four days later, these two men as well as Spock; the social critic, lawyer, and author Marcus Raskin; and Mitchell Goodman, a writer and teacher (latter dubbed the “Boston Five” by the press) held a demonstration in front of the Department of Justice in Washington, DC, which included an attempt to turn in nearly 1000 draft cards.6 These events led the federal government to bring charges against the Boston Five. It is worthwhile to look at the “Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority”7 to see a part of the government’s case.

Briefly, the nine points in this document were:

- The war is a moral and religious offense.

- The war, having not been declared by Congress, is unconstitutional and illegal.

- The war has produced events such as summary executions and the internment of civilian non-combatants that were defined as war crimes at Nuremburg.

- Those opposed to the war are denied religious liberties.

- There is a legal and moral duty to oppose this war and to encourage others to do so.

- Resistance is courageous and justified.

- Resisters should be supported.

- These activities are protected by the First Amendment’s right to free speech.

- We call on universities to enlighten the public, and on religious organizations to “honor the heritage of brotherhood.”

The government charged the five men with conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act of 1948, which makes it a crime to counsel, aid, or abet someone refusing registration in the armed forces. Although these five had barely met each other, the charge of conspiracy was used because it “relaxes the rules of evidence,” often results in harsher sentences, “and holds all conspirators responsible for the acts of each.”8

The five men, in fact, were “virtual strangers” to each other. During juror selection “all women, Blacks, and intelligent-looking people, and apparent intellectuals, such as a young man carrying a book, were excused.” The goal of the trial was thought to be to “stifle organized public opposition to the war.”9

Four of the five were convicted and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

On appeal, the court ruled that the judge in the first trial had overstepped his authority by giving to the jury a list of ten yes-or-no questions to be answered as part of their deliberations. This list may have been composed in collaboration with the prosecution.10

The actions of the five men were covered by the right to free speech as guaranteed in the First Amendment. The guilty verdict was overturned. Dr. Spock continued to write and to participate in political activities.

References

- Rudolf Virchow. Wikipedia.

- Benjamin Spock. Wikipedia.

- Benjamin Spock and Mitchell Zimmerman. Doctor Spock on Vietnam. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1968.

- NA. Spock, Benjamin. The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. kinginstitute.stanford.edu. ND.

- Spock. “Dr. Spock.”

- Robert Strassfeld. “Lose in Vietnam, Bring the Boys Home,” North Carolina Law Review, 82(5), 2004. scholarlycommons.law.case.edu.

- Resist, Inc. “A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority,” 1967. web.archive.org.

- Bud Schultz and Ruth Schultz. It Did Happen Here, Berkely: University of California Press, 1989.

- Alan Dershowitz. “They were virtual strangers yet the government charged them with conspiracy. Book Review of The Trial of Dr. Spock, by Jessica Mitford,” New York Times, September 14, 1969.

- NA. Mitchell Goodman. Wikipedia. ND.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D. was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Winter 2022 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply