Jack E. Riggs

David B. Watson

Morgantown, West Virginia, United States

|

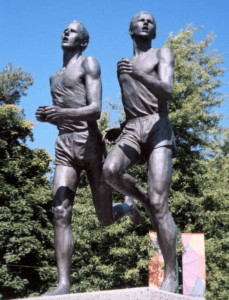

| Statue of Roger Bannister (left) and John Landy (right) at moment Bannister took the lead in their race on August 7, 1954. Statue by Jack Harman, 1967. Photo by Paul Joseph, 2005. Via Wikimedia. CC BY 2.0. |

Give me one moment in time

When I’m racing with destiny

Then in that one moment of time

I will feel, I will feel eternity

– Albert Hammond and John Bettis, “One Moment in Time”

Sir Roger Bannister is perhaps the most famous neurologist in history, yet few associate his name with neurology. His fame rests not in medicine, but rather as the first individual officially acknowledged to have run a mile in less than four minutes.

Bannister, in his 1955 book First Four Minutes, wrote, “I must try to steer a course between false modesty on the one hand and conceit on the other…It will be difficult to describe how moments when running seems utterly insignificant alternate with moments when it threatens to engulf me” (pg. 13).1

Bannister succinctly described the strategy of running the mile: “The decision to ‘break away’ results from a mixture of confidence and lack of it. The ‘breaker’ is confident to the extent that he suddenly decides the speed is slower than he can himself sustain to the finish. Hence he can accelerate suddenly and maintain his new speed to the finish” (pg. 21).1 The tactic is to be paced as fast as sustainably possible until that moment of breaking away.

Bannister, in 1949 at Princeton, met Jack Lovelock who had set a world record for the mile in 1933. Lovelock told Bannister that “in every race there was a moment when the burst was least expected” (pg. 83).1

Bannister began preparing. “It was Autumn 1950 and two years before the next Olympic Games in Helsinki. I worked out a plan…hoped to meet most of the opponents I was likely to race against in Helsinki. This would help me to find out their special points, and if possible their weak spots” (pg. 108).1

In 1951, “It was a very quiet affair – an evening match between Chris Chataway’s club (Walton) and Imperial College…This was the first of many occasions when Chris Chataway helped me with the pacing in the early stages” (pg. 123).1

At the Helsinki games, Bannister came in fourth place by 0.6 seconds in the 1500 meters. “My only chance to win an Olympic title was over,” he said (pg. 160).1 “If one fails in the Olympics there is no second chance – the years of waiting would seem an eternity of hopelessness” (pg. 161).1

“To justify my sacrifices I had to have some goal…I came near to stopping running after the Olympic Games…It was almost certain that full-time hospital work would prevent me from taking part in the Olympic Games of 1956…At last I decided that whatever the cost…I would continue running competitively for two more years” (pg. 163).1 Had Bannister won an Olympic medal at Helsinki, history would likely have played out quite differently.

“It was the rivalry between Haegg and Anderson that brought the four-minute mile within sight” (pg. 166).1 These two Swedish runners each set three world records as they lowered the mile time from 4 minutes and 6.2 seconds in 1942 to 4 minutes and 1.4 seconds in 1945. “But what about the four-minute mile? At first I thought of this merely as a new record” (pg. 167).1 “But would it mean more than any other world record being broken?…If time is the real object of the race, other competitors must be ignored, unless they co-operate wittingly or unwittingly, in the time schedule” (pg. 168).1

“The Oxford track should be the scene of my attempt at the four-minute mile. The Oxford v. A.A.A. match provided the first opportunity of the 1953 season” (pg. 170).1 “Then Chris Brasher, who ran the first two laps at a snail’s pace, loomed on the horizon in front of me, but a lap in arrears. He proceeded to encourage me by shouting backwards over his shoulder” (pg. 176). Bannister ran that mile on June 27, 1953 in 4 minutes and 2 seconds, third fastest mile of all time. The British Amateur Athletic Board stated, “Although it has no doubt that the time was accomplished, it cannot recognize the performance as a record…it does not consider the event a bona fide competition” (pg. 178).1 Had Bannister broken the four-minute barrier in that race, his name would have been forever and hopelessly tarnished.

Finally, on Thursday, May 6, 1954, teammates Brasher and Chataway served as pacers for Bannister, keeping the pace fast enough for Bannister to break the barrier with his final burst. Mission accomplished, goal achieved: 3 minutes 59.4 seconds. “We had done it – the three of us!” (pg. 193).1

Bannister held that world record for only forty-six days. John Landy would run the mile in 3 minutes and 58 seconds on June 21, 1954. However, “My four-minute mile was secure” (pg. 199).1 It was not the world record that mattered, it was being the first to break the barrier. Records are made to be broken, but being the first to break a barrier occurs only once.

Bannister faced John Landy at the British Empire Games in Vancouver on August 7, 1954. “My plans were extremely simple. I had to force John Landy to set the pace of a four-minute mile for me” (pg. 202).1 Bannister would best Landy, and both men would run sub-four-minute miles (Figure).

Critics of Bannister exist,2 but his barrier-breaking fame remains intact. Bannister published his autobiography Twin Tracks3 in 2014, demonstrating that his life was more than a race that occurred on May 6, 1954. “I grew interested in medical problems related to running” (pg. 110).1 That interest would result in Bannister becoming an accomplished autonomic neurologist.4

As Bannister feared, however, running and May 6, 1954 “engulfed” him. But, after all, that was his goal: that moment allowed him to “feel eternity”. Two fortunate failures set him up for ultimate success, as is often the irony of life.

“You always pass failure on your way to success.” – Mickey Rooney

References

- Bannister, R. First Four Minutes. London: The Sportsman Book Club, 1956.

- Bale, J. How much of a hero? The fractured image of Roger Bannister. Sport in History 2006; 26: 235-247.

- Bannister, R. Twin Tracks, The Autobiography. London: The Robson Press, 2014.

- Mathias, CJ. Sir Roger Bannister (1929-2018) and his lifetime contributions to autonomic medicine. Clinical Autonomic Research 2019; 29: 5-8.

JACK RIGGS, M.D. is a Professor of Neurology at West Virginia University.

DAVID WATSON, M.D. is Professor and Chair of Neurology at West Virginia University.

Winter 2022 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply