Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, United States

“There seems to be practically no doubt now that women are and will be doctors. The only question really remaining is, how thoroughly they are to be educated . . .”

—Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays1

In 1860s Great Britain, few women could practice medicine. The first was Elizabeth Blackwell. She was born in England but had trained and earned a medical degree in America before returning to England. The second was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had trained as a physician but was only able to qualify to practice through the Society of Apothecaries.2

After Blackwell had been made a doctor, the Medical Act of 1858 was passed, which prevented any doctor with a non-British degree from receiving a British license. Immediately after Garret Anderson was licensed, the Society of Apothecaries changed their by-laws to ensure that women could not be licensed through their organization.3 From this, one may deduce that medical education for women was restricted worldwide. But this was not the case. In France, Switzerland, Italy, America, Russia,4 and even Japan5 women were studying or licensed to practice medicine.

British women were not ignorant of this fact. Some, such as the bombastic Sophia Jex-Blake, wanted an education and were willing to fight for it. Jex-Blake began her medical education in America, taking classes under Drs. Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell. After returning to England, Jex-Blake selected the University of Edinburgh to continue her education. It was highly prestigious, had an “enlightened” admission policy, and was home to Professor Sir James Young Simpson, a supporter of women in medicine who had previously employed Dr. Emily Blackwell.6

Jex-Blake’s application was initially accepted by the University of Edinburgh. However, in 1869 the University Court and Senate decided that women could not attend classes alongside men and educating just one woman was not worth the effort.7

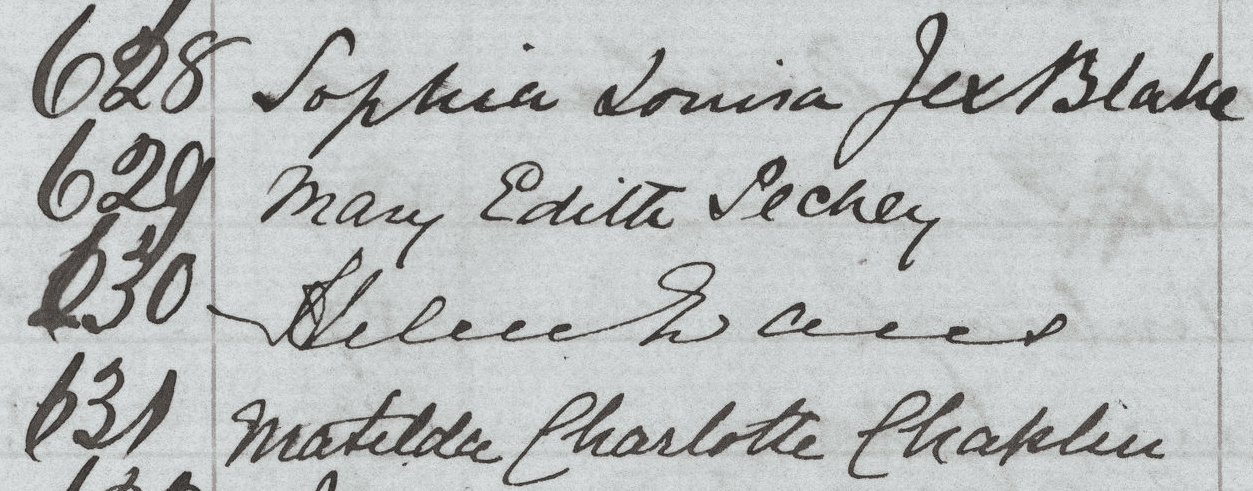

In October of 1869, Jex-Bake would return with four other women (later joined by two others) to challenge the university’s rejection. Sophia Jex-Blake, Edith Pechey, Isabel Thorne, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Mary Anderson, and Emily Bovell formed the Edinburgh Seven.8 Met with a persistent class and persuaded by Sir James Young Simpson, the university allowed the women to enroll.9

Initially, the women faced only minimal trouble. They were required to attend separate classes from the men—which meant higher fees, as medical teachers were paid based on class size10—and some professors refused to teach them.11 Jex-Blake reported that “the instruction given to us and to the male students was identical, and, when the class examinations took place, we received and answered the same papers . . .” This was reassuring. Forcing women to attend separate classes was meant to allow professors to alter class material and remove anything deemed offensive.

Spring exams came around. Edith Pechey ranked at the top of the chemistry class, making her eligible for the Hope Scholarship. However, the chemistry professor decided that the women had not been part of the same class as the men, and so were not eligible for the scholarship.12 He gave alternate completion certificates to the women (rather than the required ones) to validate withholding the scholarship. The women objected and eventually received the correct certificates, but the scholarship was still withheld.13 Instead, it was given to the next in line, a man.14

More and more professors began to exclude the group from their classes. To compensate, the seven pursued classes at the extra-mural school.15 Sir James Simpson died in May of 1870, and the women lost their most prestigious supporter.16 Their opponents rallied and push-back increased.17 Where before they faced only occasional rude behavior, now male professors and students vocally opposed their attendance.18

Still, they had completed enough courses to begin their practical clinical education. Edinburgh students traditionally trained at the Royal Infirmary. The hospital, however, was sponsor funded, and they feared that allowing the women to study would discourage sponsors. In an initial vote, sixteen of the nineteen medical staff voted against allowing the women onto the wards.19 They worried that the women would come face to face with the worst diseases and illnesses on the ward, which would, as was the constant refrain of their objectors, “offend their delicate sensibilities.”20

The women appealed for admission, making arrangements with individual clinic heads as they had with their professors. By the time the second vote was called, three medical officers had invited them to their wards, promising that they would be able to provide them instruction separate from male students. It was not enough, and they were voted out a second time.21

Rejected by the hospital, male students now shut doors in their faces, crowded their seats in lecture halls, and laughed mockingly whenever they appeared. It was a clear attempt to make the women so uncomfortable they would choose to leave before they were forced out.22

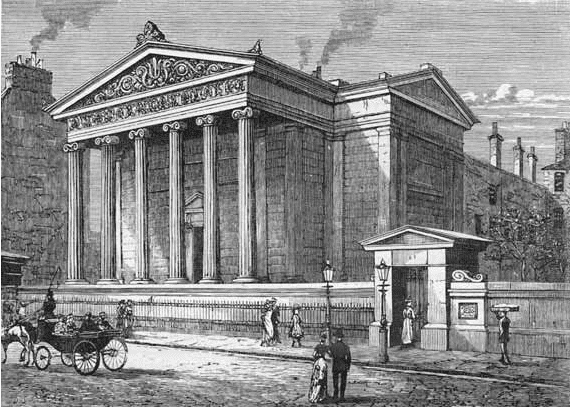

This reached a head in November of 1870, during an anatomy exam at Surgeon’s Hall. The seven women approached the hall for their exam and were met by a loud mob blocking the entrance to the building, shouting obscenities and throwing mud and trash at them. Sympathetic students broke through the crowd to open the gates and let them inside.23, 24, 25, 26

After completing their exam, their anatomy professor suggested they leave through the back entrance to avoid the remaining crowd. All declined and instead called on the “courtesy and chivalry” of the men in their class.27 They were escorted out and were later accompanied to classes by a group of men called The Irish Brigade.28 In the aftermath, newspapers reported the men’s behavior as “undignified” and “unbecoming.”29

Jex-Blake felt that the riot had been provoked by male faculty, specifically Dr. Robert Christison. In a speech, she named Dr. Christison and accused his assistant, Mr. Craig, of attending the riot, using foul language, and being publicly intoxicated. In June of 1871, she was charged with libel. The jury found her guilty. The jury ordered her to pay one farthing in damages but the judge raised the cost to 900 pounds, which was paid by her supporters.

By this point, the women needed to petition the university to take their final exam. After consulting lawyers, appealing to the University Senate, and presenting a petition signed by 9,127 women, in 1872 the University Senate agreed that the women were entitled to graduate since they had been admitted.30, 31, 32

Almost immediately, the university appealed this ruling. In June and July of 1873, the Court of Session ruled that the university never had the power to admit the women in the first place, meaning that it held no obligation to the women who had attended classes there.33, 34 The women would not be given their exams, and they would not graduate and receive degrees from the University of Edinburgh.35

This conclusion represented the culmination of a complex web of beliefs. Those opposed felt that women could not be physicians because death and disease may offend the “moral sensibility” supposedly innate to women.36 This argument was made “for their own sakes”—to protect the women, believing them unable to judge their own strength.37 At the same time, women stood as a threat to the medical degree. Many alumni felt that admitting women would lower the reputation of their degrees. Joseph Lister, professor of surgery at the university, said that women “invading” already large classes “is much to be lamented,” suggesting that medical schools did not have resources to spare on apparently lesser female students.

Some professors felt that admitting women was premature. Women had not proven they could be doctors (ignoring already successful female physicians such as Blackwell), and so by allowing them to earn a medical degree “they would acquire rights and privileges of the most extensive kind.”38 Essentially: allowing women to become physicians would dilute the power held by male physicians, opening up what had been an exclusive class- and gender-based position of prestige.

In response to these arguments, many pointed out that nurses were already accepted in medicine. As nurses, women experienced equally as many horrors as male physicians—including in nightmarish military hospitals.39 If medical knowledge was truly objective, and if women had already demonstrated the strength of nerve to serve as nurses, then there was no reason that women could not be physicians.40 Rather than debating if women were intelligent enough to receive a medical education, advocates felt that women should be given equal instruction and equal examination. If they were able to pass, it would prove that they were as intelligent as men. If they could not the evidence would speak for itself.41, 42 But these and other arguments were not enough in the case of the Edinburgh Seven.

Five of the seven went abroad to receive a medical degree. Sophia Jex-Blake and Edith Pechey graduated from the University of Berne in 1877.43 Parliament passed a revision to the Medical Act in 1876, likely spurred by the treatment the women had received. The Russell Gurney Enabling Bill allowed those with degrees from any university to apply for British medical licenses. In May of 1877 Jex-Blake was finally able to sign her name on the British medical register.44 The University of Edinburgh would allow women to graduate beginning in 1894.45

The story of the Edinburgh Seven is, of course, one of courageous and powerful women who we can look to as role models. But it also serves as an important reminder that success is often dependent on systems that can be bent by a select few to deny and exclude.

End notes

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays (Edinburgh: Wiliam Oliphant & Co., 1872). https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52297/52297-h/52297-h.htm

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Escape from the Private Sphere: the Campaign for the Medical Education of Women 1869-1878″ in “Women in Medicine in late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Edinburgh: A Case Study” (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1998), 28-29.

- Ibid.

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays.

- Mariel Tishma, “The life of a trailblazer: Ogino Ginko, one of the first female doctors in Japan,” Hektoen International Journal, Physicians of Note (Winter 2021), https://hekint.org/2021/03/29/the-life-of-a-trailblazer-ogino-ginko-one-of-the-first-female-doctors-in-japan/

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 26, no 4 (1996): 629, https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/college/journal/royal-medical-society-and-medical-women.

- M. A. Elston, “Edinburgh Seven (act. 1869–1873),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Sept 23, 2004: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/61136.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 33.

- Hamish MacPherson, “Back in the Day: Surgeons’ Hall riot that changed minds about women doctors,” The National (Glasgow), Nov. 15, 2020, https://www.thenational.scot/news/18872376.back-day-surgeons-hall-riot-changed-minds-women-doctors/.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 631.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 33.

- Ibid.

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays.

- Kristine Swenson, “Sex and Fair Play: Establishing the Woman Doctor,” Medical women and Victorian fiction (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 88.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,”, 34-35.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 631.

- Hamish MacPherson, “Back in the Day: Surgeons’ Hall riot.”

- Laura Lynn Windsor, Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 109.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 36.

- Hamish MacPherson, “Back in the Day: Surgeons’ Hall riot.”

- The Englishwoman’s review of social and industrial questions (New York: Garland Publishing, 1979), 131. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31970026821071&view=1up&seq=151&skin=2021

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays.

- Hamish MacPherson, “Back in the Day: Surgeons’ Hall riot.”

- Kristine Swenson, “Sex and Fair Play,” Medical women and Victorian fiction, 88-89.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 633.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 36.

- “The Female Medical Students in Edinburgh,” The Glasgow Herald, Nov. 22, 1870, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=trZEAAAAIBAJ&pg=955,4643728.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 634.

- Kristine Swenson, “Sex and Fair Play,” Medical women and Victorian fiction, 88-89.

- Laura Lynn Windsor, Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia, 109-110.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 636.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 38-39.

- M. A. Elston, “Edinburgh Seven (act. 1869–1873).”

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 636.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 40.

- Ibid, 32, 35.

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays.

- Ibid.

- Kristine Swenson, “Sex and Fair Play,” Medical women and Victorian fiction, 88-89.

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 35-36.

- Sophia Jex-Blake, Medical Women: Two Essays.

- Margaret Ross, “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women,” 642.

- M. A. Elston, “Edinburgh Seven (act. 1869–1873).”

- Elaine Thomson, Chapter 1, Section 4 “Women in Medicine,” 41-42.

- Laura Lynn Windsor, Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia, 110.

References

- Elston, M. A. “Edinburgh Seven (act. 1869–1873).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Sept 23, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/61136.

- Jex-Blake, Sophia. “Medical Education Of Women.” The British Medical Journal 2 No. 1453 (Nov. 3, 1888): 1023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20217774.

- ______. Medical Women: Two Essays. Edinburgh: Wiliam Oliphant & Co., 1872. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52297/52297-h/52297-h.htm

- MacPherson, Hamish. “Back in the Day: Surgeons’ Hall riot that changed minds about women doctors.” The National (Glasgow), Nov. 15, 2020. https://www.thenational.scot/news/18872376.back-day-surgeons-hall-riot-changed-minds-women-doctors/.

- Ross, Margaret. “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women.” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 26, no 4 (1996): 629-644. https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/college/journal/royal-medical-society-and-medical-women.

- “Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake, first British woman doctor.” Hektoen International Journal. Physicians of Note (Fall 2019). https://hekint.org/2019/12/11/sophia-louisa-jex-blake-first-british-woman-doctor/.

- Swenson, Kristine. “Sex and Fair Play: Establishing the Woman Doctor.” Medical women and Victorian fiction. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005.

- The Englishwoman’s review of social and industrial questions. New York: Garland Publishing, 1979. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31970026821071&view=1up&seq=151&skin=2021

- “The Female Medical Students in Edinburgh.” The Glasgow Herald, Nov. 22, 1870. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=trZEAAAAIBAJ&pg=955,4643728.

- Thomson, Elaine. Chapter 1, Section 4 “Escape from the Private Sphere: the Campaign for the Medical Education of Women 1869-1878″ in “Women in Medicine in late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Edinburgh: A Case Study” PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1998.

- Windsor, Laura Lynn. Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002.

MARIEL TISHMA is an Assistant Editor at Hektoen International. She has been published in Hektoen International, Bloodbond, Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.

Leave a Reply