Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

The Belgian artist James Ensor (1860-1949) was born to a Belgian mother, Maria Catherina Haegheman, and an English father, James Frederick Ensor. He was born and spent his entire life in Ostend, a summer resort town on the Belgian North Sea coast. The senior Ensor was not successful in business. He had severe depression that he self-treated with alcohol and heroin. The family was supported by the souvenir and curio shop run by Maria Catherina. The shop did a good business in the summer months, and little business the rest of the year.

The younger James left school at age fifteen in order to study art. His father was the only family member who encouraged and supported this pursuit. The household consisted of his mother, father, grandmother, aunt, and sister. Later, his sister’s daughter also became part of the household. Ensor’s father died in 1887, leaving him the only male in a family with some domineering (his mother) and disturbed (his sister) women.

Ensor was a member of a generation that produced “decadent art.” The French word décadent does not mean the same thing as the English word, which connotes moral decline. The French word reflects its Latin origin, decadentia, meaning “to decay.” Decadent art uses themes of internal experience “transcended into disgust, either by producing ‘disgusting’ images or by attempting to induce disgust with a given social issue.”1

One of the ways that Ensor induced disgust through his art was in the depiction of vomiting. Rather than approach the examples of this in chronological order, it is more logical to divide the works into three groups: political criticisms, non-classifiable, and personal responses to life.

The Strike (1888) depicts a real event. The fishermen of Ostend protested the importation of cheaper fish into the port, a threat to their income. Their strike was met with force, and Belgian gendarmes shot and killed two strikers. In the painting, two strikers on a balcony are vomiting fish on the police below.

In Doctrinal Nourishment (1889), Ensor’s disdain for authority is clear.2,3 A row of larger-than-life-sized people, representing the king, a bishop, a general, a nun, and an education minister, have their backs turned to us. Their buttocks are exposed and they are defecating on a crowd of workers and the bourgeoisie, in other words, everyone. The sun, seeing the people accepting the lies of the ruling class, vomits on this scene.

Plague Above, Plague Below, Plague Everywhere (1904) has four well-dressed citizens sitting on a bench, under which is a pile of freshly passed feces. At one end of the bench stands a woman in rags, holding a dead baby.4 Two poor, barefoot fishermen are at the other end of the bench, holding rotten fish. Here, too, the sun is vomiting on the scene of poverty amidst plenty.

The Banquet of the Starved or Comic Repast (c. 1917-1918) was painted during the German occupation of Belgium during the Great War. A group of seven masked people sit at a table to have a meal that includes an onion, insects, and two small carrots. One man vomits. On the wall above them hangs an Ensor painting of two skeletons fighting over a dried herring, further accentuating the contents of a wartime starvation diet.5,6

In the etching The Battle of the Golden Spurs (1895), Ensor, a proud Fleming, depicts the 1302 battle of the French army with rebellious Flemish forces in Courtrai (Kortrijk), Belgium. Two wounded soldiers are vomiting.

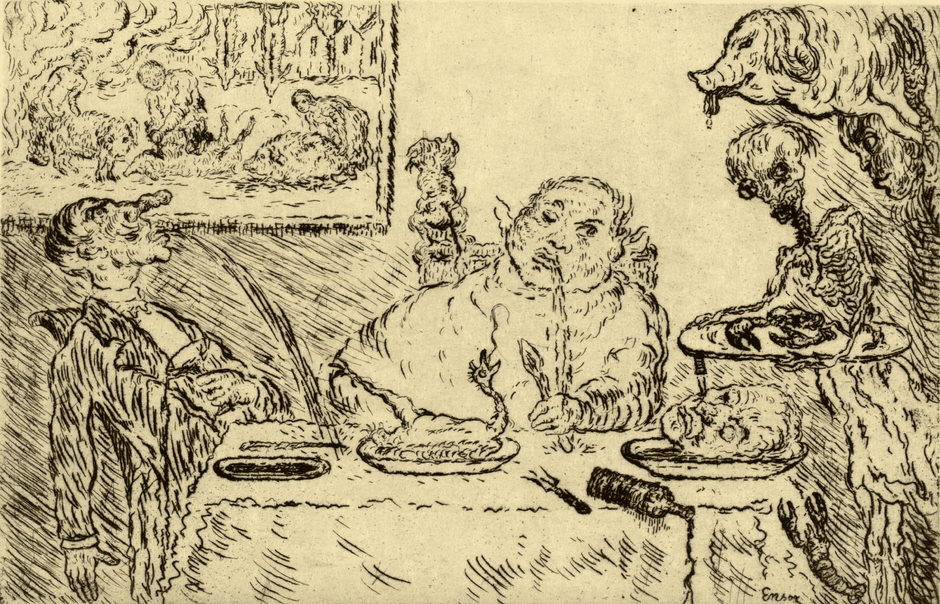

Two instances of “non-classifiable” vomiting can be found. The Combat of the Rascals Désir and Rissolé, an etching from 1888, has one man vomiting. In Gluttony (1904), two gluttons are vomiting during their meal.

Vomiting was used in several works to express Ensor’s personal, non-political concerns. The etching Death Chasing the Flock of Mortals (1896) reflects Ensor’s “preoccupation with his own mortality.”7 One person is vomiting at the sight of the Grim Reaper.

In At the Conservatory (1902), a man is apparently vomiting because of the quality of the singers and musicians. A picture on the wall has Wagner sticking his fingers in his ears.

The Cathedral (1896) shows a massive crowd before a gigantic cathedral. Ensor hated organized religion but loved the idea of Jesus.8 There is one person in the enormous crowd who is vomiting. Could it be Ensor?

The art critics Octave Maus and Édouard Fétis9 are seen in The Dangerous Cooks (1896) preparing to serve Ensor’s head (labeled “ART ENSOR”) to a group of five diners, two of whom are vomiting in anticipation of seeing Ensor’s work. Ensor had a long history of animosity toward art critics. They called his work “garbage,” “sinister idiocies,” and “ignoble sights.”10 Ensor had been a founding member of a group of avant-garde artists, Les Vingt or Les XX (the Twenty), started in 1883 by Octave Maus. When Ensor produced his masterpiece Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888), not only would Les XX not put it in their exhibition, but they also attempted to expel Ensor from the group. They failed, lacking just one more vote needed for expulsion.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is an enormous painting, 253 cm x 431 cm, or about eight by fourteen feet. A tremendous crowd has assembled for the event. Jesus is a small figure, barely recognizable,11 seated on a donkey in the center of the painting. No one is looking at him. The atmosphere seems to be one of a carnival or fair. The people participating in this chaotic scene are “celebrating, rather than understanding”12 what they are seeing. Ensor, who was introverted and often felt alone, mocked, and persecuted, identified with Jesus.13 In one corner of the painting, there is a green banner with Les XX written on it. A man (Ensor?) is vomiting on it. The painting remained in Ensor’s room in Ostend until its first public showing in 1929, forty years after its creation.

In Ensor’s words, “To be artists, let us live in hiding/Disparagement beats down on me like hail . . . /I’m abused, I’m insulted . . . /I’m mad, I’m simpleminded/I’m nasty, wicked, incapable, ignorant/A creampuff gone rotten.”14

Greil Marcus15 quotes art historian Libby Tannenbaum (1951), that Ensor had “resentment and hatred of mankind,” and Luc Sante (1998), that Ensor was “the most deadly cynic in the history of art.” His misanthropy also included a hefty share of misogyny. His poem “On Women” (1925)16 starts, “A swamp, crawling with bad beasts/Liquid manure, sticky and oozing with vermin/Sneaky and hostile morass/ Horrible cess-pit teeming with leeches.” He had no relationships (other than in writing) with adult women during his lifetime.

Ensor also composed and played music, as well as writing poetry and articles about art.17 In 1999, the J. Paul Getty Museum published a book that paired details from Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 with the lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” (1965). Music critic and Dylan scholar Greil Marcus wrote18 about “Desolation Row” that the listener is directed to “a circus of grotesques.” All the characters are “prisoners of judges, doctors, torturers . . . secret police. Prisoners of their own ignorance, vanity, their own compromises, cowardice.” James Ensor, he says, went much further in his time than Dylan did in 1965, or in the years since.

Ensor did not imagine that someday he would be appreciated in Belgium, let alone the wider world. “Ostenders,” he said,19 “detest art. Last year thirty Ostenders came to see the exhibition. This year we will reach the number thirty-one.”

References

- Kaylee Alexander. “Descent from the cross: James Ensor’s portrait of the symbolist artist,” Shift: Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture, 2017. academia.edu

- Jojada Verrips. “Excremental art: Small words in a world full of shit,” J Extreme Anthropology, 2017. pdfs.semanticscholar.org

- NA. “The scandalous art of James Ensor.” ND. getty.edu

- NA.” Ensor is scandalous and defiant,” Colorado Business Roundtable, 2014.

- NA. “James Ensor, “Comic Repast” (“Banquet of the Starved”), Metropolitan Museum of Art, ND. metmuseum.org

- Katherine Kula. “‘Me and my circle’: James Ensor in the twentieth-century,” Master’s Thesis, 2010. drum.libumd.edu

- Carol Zemel.”Book Review: Diane Lesko. James Ensor, the creative years, Princeton University Press, 1985,” In The Art Bulletin, 70(1), March 1988.

- Greil Marcus. “Where is Desolation Row?” Threepenny Review, 1999.

- Sura Levine. “James Ensor,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 9 (1), 2010.

- Bruce Dwyer. “Pariah to paragon: James Ensor and the carnivalesque,” Dissertation, 2007. utampa.dspacedirect.org

- James Ensor and Bob Dylan, John Harris (ed.). “The Superhuman Crew,” Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1999.

- Patrick Reuterswärd. “Kommanterer till de enskilda verken. Krist intåg i Jerusalem,” In En liten bok om Ensor, Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1970.

- Marcus. “Desolation Row.”

- Sandra Mackenzie. “‘I’m a creampuff gone rotten.’ James Ensor on art and life,” Royal Academy of Arts, 2016. royalacademy.org.uk

- Marcus. “Desolation Row.”

- NA. Transcript of “Old Lady with Masks,” podcast. ND. liverpoolmuseums.org.uk

- Mackenzie. “Creampuff.”

- Marcus. “Desolation Row.”

- Mackenzie. “Creampuff.”

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. He studied medicine at the Université Catholique de Louvain and is fond of Belgium and things Belgian.

Leave a Reply