John Rasko

Carl Power

Sydney, Australia

|

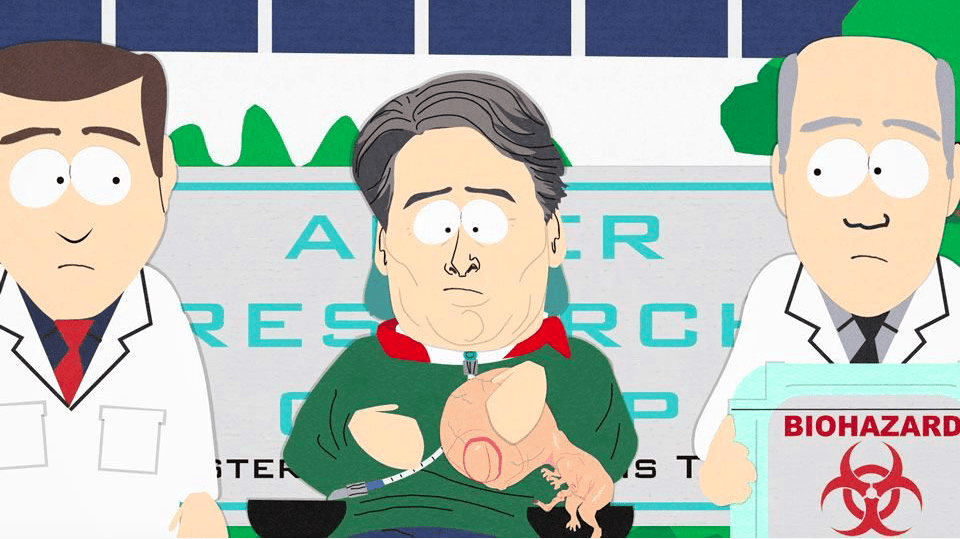

| Christopher Reeve comes to South Park to demonstrate all the hope and horror of embryonic stem cells. Trey Parker and Matt Stone, “Krazy Kripples,” South Park, season 7, episode 2 (2003). |

The creation of human embryonic stem cells in 1998 sparked enormous excitement.1 The superpower that embryos possess—the ability to generate all cell types found in the body—was suddenly within our reach. The era of “regenerative medicine” seemed to be dawning. In the words of one science writer: “Human embryonic stem cells represent an epochal technological breakthrough, as revolutionary to medicine as the metal age was to industry.”2 Miracles were promised—the lame would walk, the blind would see—and this before embryonic stem (ES) cells had demonstrated any therapeutic worth at all.

But the dream of regenerative medicine brought with it a nightmare. Pro-life groups railed against ES cell research, accusing it of murdering unborn children. In their view, it was a symptom of moral depravity, proof of what Pope John Paul II (and others) described as the modern “culture of death.”3

ES cell research became a key battleground in the ongoing culture war between conservatives and progressives. Perhaps none have presented the stem cell controversy more outlandishly than Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the makers of the cult television show South Park. In an infamous episode, “Krazy Kripples,” they took aim at the actor Christopher Reeve, a celebrity campaigner for ES cell research.4 Apparently, Parker and Stone had qualms about making it, fearing that Reeve was too well-loved to be savagely ridiculed. Reeve had become famous for playing Superman in a string of hit movies in the 1970s and 80s before a horse-riding accident left him quadriplegic. Embryonic stem cell research could not have had a better ambassador. Popular, articulate, and wheelchair-bound, he spoke for all those in need of a stem cell miracle.

As Parker recalls, he and Stone sat on the episode for a full year. But in 2003 they had run out of ideas and reached for it in desperation. Also, they were annoyed by Reeve’s appearance on Larry King Live and thought, “You know what? F**k him. He really is taking up this cause of ‘Everyone needs to help me out.’”5

In “Krazy Kripples,” Christopher Reeve comes to South Park to demonstrate the miraculous benefits of embryonic stem cells. In the key scene, he sits in his wheelchair, flanked by a pair of white-coated scientists, outside an ultra-modern research facility, where a crowd has gathered to hear him speak. “Thank you, everyone. To most people, this is just an ordinary fetus,” he says, taking one out of a biohazard box. “But to people like me, it’s hope.”

He holds it high so everyone can see, then proceeds to snap its neck and suck out its juices. The crowd gasps. Then, tossing the empty fetus to the ground, Reeve slowly steps out of his wheelchair and raises his arms in triumph. The crowd bursts into applause. A newsreader speaking to camera makes this report: “Tom, many celebrities have spoken out in protest of stem cell research. But, after seeing this, how can they protest now?”

This willfully appalling scene—a prime example of gross-out humor—sums up the hope and the horror of embryonic stem cells. As if seen through a funhouse mirror, both are exaggerated extravagantly. On the one hand, the promise of ES cell research is more than fulfilled. Reeve not only regains his ability to walk, he also acquires the superpowers of his most memorable screen character, at one point tossing a truck at his opponents. On the other hand, the use of embryos could not be presented in a more repugnant way. The stem cells in the episode are not extracted from a microscopic blastocyst, cultured in vitro, differentiated into the required tissue type, and administered by a team of doctors. Rather, Reeve simply sucks them straight from the necks of unborn babies. It is a graphic depiction of what pro-life campaigners have always asserted: that creating and then killing embryos to treat another person’s maladies is a kind of “cannibalism,” something that no civilized society should tolerate.6

In the world of South Park, both sides of the debate are right: ES cells come from dead babies and they have miraculous healing powers. Moreover, the horror of one (gasp) leads so directly to the triumph of the other (applause), that the two seem intimately—even causally—connected. This connection is, we think, of great importance. Whether or not Parker and Stone realize it, they have uncovered, beneath the dream of regenerative medicine, something of its dream logic.

Jamie Thomson, the man who created the first human ES cells, has acknowledged that pro-life hostility kept stem cell research in the spotlight year after year, preventing it from becoming a “normal science.”7

But we can go further by suggesting that the controversy encouraged those who championed ES cell research to exaggerate its medical potential. If, as the bioethicist Ronald Green has said, the best way to silence the critics is to prove that ES cells really can cure disease,8 while you wait for that to happen, the next best strategy is to talk up their therapeutic promise loudly and often. That way, everyone is clear about how much will be lost if research does not proceed.

The dream of regenerative medicine arose from, and fed back into, the stem cell controversy. As opponents maximized the moral harm caused by ES cell research, supporters maximized the medical benefits it promised. The more one side damned it, the more the other praised it, so that a mortal sin became the means of salvation. South Park presents us with the conclusion of this dialectic: dead babies = medical miracles.

There is another, even weirder, way to derive this same equation. Stem cell therapy is, as Parker and Stone show, a form of cannibalism and this, strange to say, is part of its appeal.

Medicinal cannibalism has a long and venerable history, even in the West. Ancient Romans would descend upon a fallen gladiator to sup on his blood or snack on his liver. These remains were thought to possess a vital force that could cure epilepsy and other ills. As the historian Richard Sugg has shown, early modern Europeans, both educated and illiterate, indulged in similar remedies on a routine basis. The corpses of hanged criminals were turned into drugs. Human blood was consumed, fresh or dried, and human fat was often used in ointments. It was only in the mid-eighteenth century that such nostrums fell out of favor, at least for the wealthy and well-bred, who wanted to prove themselves enlightened, rational, free from superstition, and superior to the common folk.9

However, cannibalism never died out, and you do not need to look far afield for contemporary examples. Every modern hospital provides them: skin grafts, blood transfusions, organ transplants and, of course, stem cell therapy. No doubt, modern medicine is chalk-and-cheese different from its magical counterpart, but this does not prevent the two from mixing together. We are all familiar with the charlatans who don white lab coats in order to sell what are effectively folk remedies. They give magical medicine a scientific makeover.

Conversely, science can fall under a spell. The high hopes inspired by medical breakthroughs frequently contain a measure of magic. Stem cell research, for instance, has been described as a modern-day effort to find the mythical fountain of youth. It is a mistake to dismiss this as just a metaphor (as it is to dismiss Parker and Stone’s take on ES cells as just a sick joke). Metaphor is one of the key principles of magical thinking.

Here we should note that the hype surrounding regenerative medicine was, in part, inherited from a pseudoscience that enjoyed great popularity in the preceding decades. Before everyone got excited about ES cells, they were clamoring for “fresh cell” therapy. Developed in the 1930s by Swiss physician Paul Niehans, this involved injecting patients with live cells from unborn sheep, cows, and sometimes even human fetuses. (He mostly used fetal calves because they were much easier to source than aborted babies and, in his opinion, worked just as well for most ailments.) Niehans presented his treatment as a heady mix of magical and modern medicine, and it worked a charm. The rich and famous flocked to his clinic on the shores of Lake Geneva, all seeking the cellular fountain of youth.10

When the makers of South Park had Christopher Reeve sucking on dead babies, they identified the magical heart of regenerative medicine, its secret ingredient. One of the reasons we have attributed great therapeutic power to embryonic stem cells is because, in our collective imagination, they represent the very essence of youth. Biotech cannibalism promises to tap the ancient wellspring of life itself.

References

- This article is drawn from chapter 6 of John Rasko and Carl Power, Flesh Made New: The Unnatural History and Broken Promise of Stem Cells (Sydney, NSW: ABC Books, 2021), https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9780733340147/flesh-made-new/. For a brief history of regenerative medicine, see Carl Power and John Rasko, “The Stem Cell Revolution Isn’t What You Think It Is,” New Scientist, 29 September 2021, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25133542-600-the-stem-cell-revolution-isnt-what-you-think-it-is/.

- Elizabeth Finkel, Stem Cells: Controversy on the Frontiers of Science (Sydney: ABC Books, 2005), 3.

- John Paul II, “Evangelium Vitae,” 25 March 1995, The Holy See, http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae.html.

- Trey Parker and Matt Stone, “Krazy Kripples,” South Park, Season 7, episode 2 (USA: Braniff Productions, 2003).

- Eric Goldman, “South Park: Matt and Trey Speak out, Part 2,” IGN News Corporation, 19 July 2006, https://www.ign.com/articles/2006/07/19/south-park-matt-and-trey-speak-out-part-2.

- For examples of embryonic stem cell research being described as “cannibalism,” see C. Ben Mitchell, “Biotech Cannibalism,” 4 April 2000, Center for Bioethics & Human Dignity, Trinity International University, https://cbhd.org/content/biotech-cannibalism; William Norman Grigg, “Medical Cannibalism,” The New American, 10 September 2001, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Medical+Cannibalism.-a078738321.

- Jane Gitschier, “Sweating the Details: An Interview with Jamie Thomson,” PLoS Genetics 4, no. 8 (August 2008): 3, online at https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1000182.

- Ronald M. Green, “Embryo as Epiphenomenon: Some Cultural, Social and Economic Forces Driving the Stem Cell Debate,” Journal of Medical Ethics 34, no. 12 (December 2008): 843.

- Richard Sugg, Mummies, Cannibals, and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians (London: Routledge, 2016), 6–7, 392.

- Paul Ferris, “The Fountain of Youth, Updated,” New York Times, 2 December 1973, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/02/archives/the-fountain-of-youth-updated-with-the-cells-of-unborn-lambs.html.

JOHN RASKO, AO, is an internationally-acclaimed leader in gene and stem cell therapies. For over two decades he has directed the Department of Cell and Molecular Therapies at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, and the Gene and Stem Cell Therapy Program at the Centenary Institute, University of Sydney. He frequently appears on radio and television programs to talk about stem cell research, medical tourism, scientific fraud, and related matters. John delivered the 2018 Boyer Lecture series for the ABC and recently authored a book with Carl Power, Flesh Made New: The Unnatural History and Broken Promise of Stem Cells.

CARL POWER is a writer in the history of medicine with degrees in both Communication and Philosophy. He has explored the concept of life throughout the ages, from the earliest creation myths to the latest fantasies of the post-human future. He is the editorial coordinator of the journal Labour History and an editorial research officer at the Centenary Institute, University of Sydney. He recently authored a book with John Rasko, Flesh Made New: The Unnatural History and Broken Promise of Stem Cells.

Leave a Reply