JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

| Fig 1. Lear by Wilhelm Marstrand 1840 NPG 3055 [public domain] |

How pleasant to know Mr Lear!

Who has written such volumes of stuff!

Some think him ill-tempered and queer

But a few think him pleasant enough.

Edward Lear 1879

Hundreds of famous people from every branch of life have been diagnosed or suspected—sometimes on dubious evidence—as sufferers from the symptom epilepsy. Edward Lear (1812-1888) (Fig 1) was afflicted by epilepsy, which may have affected his lifestyle, creative drawings, paintings, limericks, and comical verses.

He was born on 12 May 1812 in Holloway, London, the twentieth of twenty-one children. Most of his siblings died in childhood, and he always had delicate health with short-sightedness, asthma, and bronchitis. Aged five, he had his first epileptic fit. At this time his home life was unstable. He was dispatched to the care of his twenty-five-year-old sister Ann, who mothered and tutored him at home and encouraged him to draw and paint.

Such was his talent that by the age of sixteen, he was producing illustrations in Prideaux Selby’s Illustrations of British Ornithology, and aged nineteen he was employed to illustrate parrots by the Zoological Society of London (Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1830-1832)). In preparation, he laboriously measured and scrutinized birds’ color, characteristics, and morphology.i His lithographic folios earned him a reputation as an illustrator of birds.1 He was elected Associate of the Linnean Society and regarded as one of the finest natural history illustrators of the nineteenth century. His prints are collected and treasured by Sir David Attenborough.

The naturalist Edward Stanley (thirteenth Earl of Derby) commissioned the self-taught twenty-year-old Lear to paint the parrots and mammals in his huge menagerie at Knowsley Hall in Merseyside. Lear then started to write funny poems and sketches, most famously The Owl and the Pussycat, and later dedicated A Book of Nonsense in 1846 to Edward Stanley’s grandchildren. It was a two-volume collection of seventy-two limerick verses (Fig 2) with funny drawings written under the pseudonym Derry Down Derry. Stanley encouraged him and funded a long stay abroad. Lear left England in 1837 and landed in Rome. For the next ten years, Italy was his base for extensive travels and a search for new subjects to paint. These years were the happiest and most stimulating of his life; the climate suited his fragile health and he mixed with famous artists, being influenced particularly by Holman Hunt.

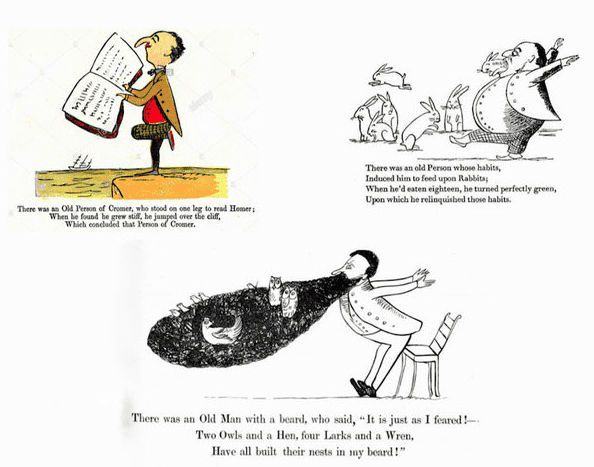

|

| Fig 2. Lear Limericks |

After a short spell at the Royal Academy in 1850, he again lived abroad,2 at first near his friend Franklin Lushington on Corfu. For a time he had an unreciprocated, emotional involvement with Lushington, but there is no evidence to suggest that he was homosexual.1

Epilepsy

His first epileptic attacks started at the age of five; they recurred ten to fifteen times each month. His sister Jane was also epileptic. Because the label was so stigmatized, he carefully concealed it from his adult friends and recorded few details of his attacks because to him, they were a source of guilt and shame.3 “The Demon,” as he called his attacks, was replaced later by the description of their depressing after-effects, “The Morbids.” He wrote:

“It is a most merciful blessing that I have kept up as I have, and not gone utterly to the mad bad sad.”

Like many of his contemporaries, he was convinced that epilepsy would lead to a deterioration of his brain and early death. He had seen his epileptic elder sister Jane have seizures, and she had died before reaching adulthood. In his forties his attacks occurred up to twenty times each month, marked by little crosses (X) in his diary.4

He kept his epilepsy secret, writing in February 1880:

It is wonderful that these fits have never been discovered, except partly apprehending them beforehand, I go to my room . . . Marked swimming in the head and a feeling of nausea,—and frightful dyspepsia—no relief till sudden X.

It is likely they were complex partial seizures, many with secondary generalization,5 that is major convulsive fits. In later life, they became more severe, always recorded in his diaries with an X, often with a score from one to ten to mark their severity. Bromides, introduced in 1857, were of moderate benefit, but I have found no evidence that Lear received them or other anticonvulsants.

![Excerpt from Edward Lear's diary. [Text reads: Wednesday, 8 March 1865 Quite fine & bright, but colder considerably. Rose 6.30. Began work 7.15 — & worked till 9. After breakfast — I wrote to J. Cross, & Mrs. Robinson. Worked — at 160 Tyrants — but suddenly X1 Very unexpected. — ]](https://b1480254.smushcdn.com/1480254/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/From-Lears-diary-300x154.png?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1) |

| From Lear’s diary |

Because epilepsy was so stigmatized in society, maintaining his secret necessitated a degree of self-imposed isolation. This may explain some aspects of his personality, periods of melancholy, and loneliness, which perhaps he countered by his art and delightful nonsense verses. For as Alexander Pope said:

And keep good humour still whate’er we lose?

And trust me, dear! good humour can prevail,

When airs, and flights, and screams, and scolding fail.ii

His nonsense verse has been considered the antithesis of the more serious aspect of his highly rated paintings. Much has been written about the possible relationship between epilepsy, art, and creativity,5 but this is largely conjectural, perhaps with the exception of the bizarre fantasies sometimes occurring in temporal lobe epilepsy, such as those of Dostoevsky.

Limericks and Art

From 1837 to 1848, seeking respite from his illnesses, he moved to Italy, where he traveled widely and earned a living as a landscape painter. He published Illustrated Excursions in Italy in 1846,6 which so impressed Queen Victoria that she invited him to give her drawing lessons.

The first known book of limericks was The History of Sixteen Wonderful Old Women published in 1820. Lear’s limericks (often set to song) showed a refreshingly witty style, filled with hilarious absurdities: nonsensical, imaginatively playful pageants of fun, ideal for children—and for not a few adults. The third edition of A Book of Nonsense appeared in 1861. To this day, A Book of Nonsense (Fig 2) has never been out of print. He never used the word “limerick,” a term introduced in the late nineteenth century.iii

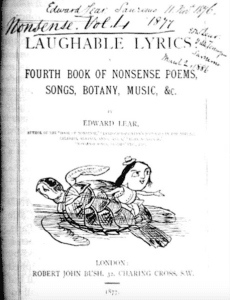

|

| Fig 3. Title page of Lear’s own copy of the book, inscribed by him: “Edward Lear. Sanremo. 11. Nov 1876. Nonsense. Vol. 4 1877 Edw Lear Villa Tennyson Sanremo March 2, 1886.” [From Justin G. Schiller, Ltd.’s Edward Lear catalogue (no. 48). |

A great friend of the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson and his wife Emily, he illustrated Tennyson’s book of poems in 1889. And when he settled in San Remo in the 1870s, he named his home “Villa Tennyson.”

He published three volumes of bird and animal drawings, seven illustrated travel books (notably Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, &c., 1851), and four books of nonsense rhymes, stories, and songs. In 1877 his Laughable Lyrics (Fig 3) contained some of his finest but also his most melancholy songs, including The Pelican Chorus, The Yonghy-bonghy-bò, and The Dong with a Luminous Nose.

Hapless in love, plagued by poor health, and distanced from his native home, he had spells of depression. And yet he consoled millions of children and adults—and perhaps himself—with his gentle wit, irreverent and romantic whimsy, and amusing neologisms. Who fails to chuckle or chortle, or flies to infantile fantasies when reading of the runcible spoon; The Jumblies who went to sea in a sieve; the hills of the Chankly-Bore; The Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò; The Pobble Who Has No Toes; the Fimble Fowl with a corkscrew leg; or The Quangle Wangle’s Hat? He did not confine his attentions to strange animals but published Nonsense Botany in 1871, which included his priceless and quirkily titled sketches Manypeeplia upsidownia, Arthbroomia rigida, and Tigerlillia terribilis.

A sedulous writer of diaries and letters (many to Emily and Alfred Lord Tennyson), to the end of his life he remained solitary, accompanied by Giorgio Kokali, his loyal Albanian manservant for twenty-seven years, and his cat Foss. Severe bronchitis in 1886 led to a worsening of his health; Foss died in that same year. Edward Lear died alone in San Remo on 29 January 1888.

Fearful that his epilepsy might be hereditary and passed on to children, he never married. Although a genial, endearing, but lonely man, he made many friends.7 The eminent critic John Ruskin wrote:

Surely the most beneficent and innocent of all books yet produced is the “Book of Nonsense,” with its corollary carols, inimitable and refreshing, and perfect in rhythm. I really don’t know any author to whom I am half so grateful for my idle self as Edward Lear. I shall put him first in my “List of the Best Hundred Authors.”

Lear would have delighted in the recognition of his work in a major exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1985, which showed him as a pioneering natural history draughtsman and landscape painter—despite a lifetime of epilepsy.

End notes

- Several new species were named after him, such as Lear’s macaw (Anodorhynchus leari), a large all-blue Brazilian parrot.

- Alexander Pope. The Rape of the Lock: Canto

- The source of the name “limerick” is a mystery and its connection with the Irish city of that name is tenuous.

References

- Noakes, V. Lear, Edward (1812–1888), landscape painter and writer. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Published online: 23 September 2004.

- Noakes V. ed., Edward Lear: the life of a wanderer, 3rd edition, London Bridge, 1985.

- Chitty, Lady Susan. That Singular Person Called Lear: A Biography of Edward Lear Artist, Traveller, and Prince of Nonsense. Athenaeum 1989.

- Hodges J. The Maker of the Omnibus: The Lives of English Writers Compared. 1992; pp.350.

- Thomas RH, Mullins JM, Waddington T, et al. Epilepsy: creative sparks. Practical Neurology 2010;10:219-226.

- Uglow, Jenny. Mr. Lear A Life of Art and Nonsense. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2018.

- Shakespeare, Tom. Collection Disabled Lives. https://farmerofthoughts.co.uk/collected_pieces/edward-lear/

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022

Leave a Reply