Joshua Obase-Otumoyi Ofor

Calabar, Nigeria

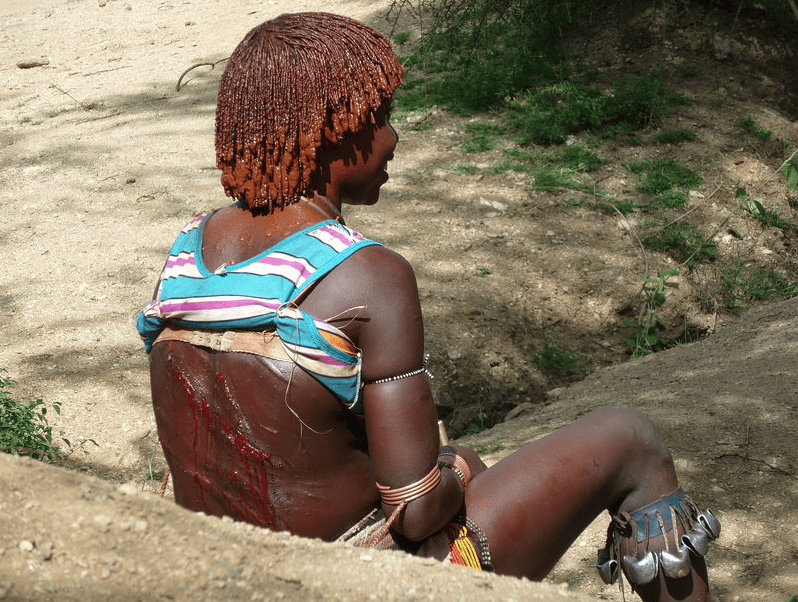

Among the various traditional practices that victimize women and girls in Nigeria, female genital mutilation (FGM) is the most reprehensible. It consists of removing part or all of the sensitive female genital organs including the prepuce, clitoris, and labia majora and minora. This surgery is done on girls of nearly all tribes—Yorubas, Igbos, and Hausas—as a transition from childhood to adolescence, to reduce sexual desire, and even to help in bargaining the bride price when they come of age to marry. The operation is done in rural areas in dirty and unhygienic surroundings with unsterilized tools, promoting the spread of blood-transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS. After FGM, cow dung is applied to the mutilated area and may cause tetanus and other infections. Scarring of the area may cause the perineum to tear at child birth and result in uncontrollable hemorrhage. In the practice of infibulation, the vagina is almost completely sealed off, leaving only a small opening for the passage of urine. In these cases, during menstruation the woman often becomes infected because the opening is too small to allow passage of menstrual blood.

The surgeries are done without anesthesia. The girls are awake during the process and suffer excruciating pain. Some experience mental breakdowns, psychotic episodes, nightmares, or depression. Some may not survive. The “excisors” are untrained women, their trade passed from mother to daughter by a watch-and-learn process. If they make the cuts too deep, nick an artery, and cause severe bleeding and even death, they are not blamed but the result is attributed to spiritual or mystical causes. In women who have undergone infibulation, they need to have the stitches of their labia majora constantly altered during pregnancy. The complications during birth are usually not handled appropriately.

Another detestable practice is early sexual intercourse and pregnancy, which has sent many young women to their grave. This barbaric practice is common among the Hausa and Fulani tribes in the Northern part of Nigeria. At the age of twelve or thirteen girls are given out for marriage and become pregnant not long thereafter. Engaging in sexual intercourse at that age may cause bleeding because the vagina is not yet fully developed. In most cases the girl is (raped) forced to please the sexual desires her husband, who is usually older than her by two decades. After pregnancy a vesico-vaginal fistula may occur as the forceful entry of the baby into the world corrodes the bladder wall.

Another medically despised practice is breast ironing (pressing), practiced by the Igbo tribe. This involves the use of a wooden spatula, stone, or hot metal on the breast during puberty to limit growth of the mammary gland. Physiological and psychological trauma follows this ancient appalling act.

Scarification (tribal mark) is another practice, perpetrated by the Hausa and Yoruba tribe. It involves cutting the skin on various regions of the body for means of identification. The cut is made with an unclean blade that promotes the transmission of HIV/AIDS and when not done skillfully it might lead to bleeding if an artery is severed.

Uvulectomy is also practiced by most tribes. It involves the removal of the uvula from the oral cavity of neonates. It is believed that the uvula carries impurities from the womb, hence it needs to be removed. These new born babies are prone to infection and most of the equipment used for these surgical practices is unsterilized.

These traditional practices have been highlighted for many years but are still allowed to continue. It is only to be hoped that future generations will not be subjected to these gruesome procedures.

References

- Omoniyi, T. O. Appraisal of harmful traditional practices in Nigeria: magnitude, justifications and interventions. Nigeria. 2020.

JOSHUA OBASE-OTUMOYI OFOR is a final year medical student of the department of Medicine and Surgery in the University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State of Nigeria.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022

Leave a Reply