James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

| Ch’ io sono quell gran medico Dottore enciclpedico, Chiamato Dulcamara, . . . Rigiovnir bramate? |

I’m noted as a scientist, Practitioner and specialist. I’m Doctor Dulcamara … Would you like your youth recaptured? |

| L’Elisir d’Amore (The Elixir of Love), music by Geatano Donizetti, Libretto by Felice Romano, Act I, scene IV1 | |

|

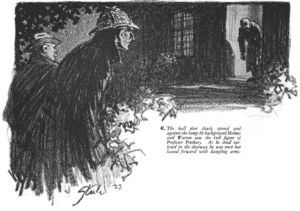

| Illustration by Frederic Dorr Steele for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Creeping Man” published in Hearst’s International in March 1923. Via Wikimeda |

“Rejuvenation” through medical science is the theme at the heart of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, “The Adventure of the Creeping Man.” The story dates from 1923 and was first published in the United Kingdom in The Strand Magazine and in the United States in Hearst’s International. It was then collected as one of twelve stories published as The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes in 1927. Dr. Watson, the narrator of the story, informs us that “certain obstacles” prevented him from telling this story for some twenty years. The events described begin in early September 1903 with a message as famous as the story itself:

Come at once if convenient—if inconvenient come all the same.

S. H.

During the two decades that preceded the setting of the story in 1903, and the two decades that followed, “rejuvenation” through what came to be called “organotherapy” was a subject of heated controversy that occupied the attention of both the medical profession and general public. Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), a physician turned author, was in his mid-sixties when he wrote the “Creeping Man” and though he had ceased to practice medicine in the early 1890s, he continued to keep himself informed on medical affairs of the day. The events in the story make it clear that he was following the controversies that swirled around “medical rejuvenation.”

In the “The Adventure of the Creeping Man,” Holmes has been consulted by Mr. Trevor Bennett, a trusted assistant to Professor Presbury, a physiologist at Camford,2 whose recent and mysterious behavior has alarmed his family. The professor is a widower who at the age of sixty-one has become engaged to Alice Morphy, the only daughter of Professor Morphy, a colleague and Chairman of Comparative Anatomy at Camford. Alice Morphy is a very attractive young woman and has a number of suitors of a more suitable age. Presbury also has a daughter, Edith, to whom Mr. Bennett is engaged.

Offering no explanation, Professor Presbury mysteriously left home for a fortnight. Mr. Bennett learns independently from a friend that the professor was seen in Prague. From that time forward, Presbury has become a very different person; irritable, distant, and secretive. Added to this, at regular intervals his beloved bloodhound Roy has tried to attack him and had to be moved to the stables and placed on a collar and chain. It is noteworthy that the dog’s aggressive behavior occurred at nine-day intervals. Mr. Bennett previously enjoyed the complete confidence of the professor and handled all his correspondence. After the professor returned from Prague, he has been forbidden to open certain correspondence coming from London. Further, he incurred the professor’s wrath while working in the laboratory by picking up a box that the professor had brought back from Prague. Holmes and Watson travel to Camford in an attempt to meet Presbury but are rudely turned away. The occasion does afford them the opportunity to gauge his personality. After Bennett observes the professor in the middle of the night creeping out of the house as well as climbing up the side of the house and peering into his daughter’s bedroom, Holmes and Watson return to Camford and during the cover of darkness of night observe the professor leaping up a tree along the side of the house and climbing to the roof. They see him cruelly taunt his dog Roy who breaks free from his chain and attacks Presbury, inflicting a severe neck wound. With Presbury incapacitated, Holmes opens the mysterious box and finds a hypodermic needle and vials of medicine. The box contains a letter from H. Lowenstein, a scientist located in Prague, along with invoices originating in London from a merchant, A. Dorak, who has been supplying the medication. The letter explains the case: Lowenstein has discovered a “serum” from a black-faced langur monkey. Lowenstein notes that he would have preferred to use a serum from an “anthropoid” because it walks erect and is nearer to a human.

|

| A Black-Faced Langur, one of several leaf and fruit eating monkeys referred to in “The Adventure of the Creeping Man.” Photographed in Central India by the author. |

When all is disclosed, Dr. Watson recalls that a scientist, “Lowenstein of Prague,” has been seeking the secret of “rejuvenescence and the elixir of life” and has been tabooed by the medical profession. Bennett has looked up “the great black-faced monkey” in a zoology text and finds that the langur is the biggest and most human of the climbing monkeys.

Given the obvious medical implications of “The Adventure of the Creeping Man,” the reader might wonder what events were occurring at the time in the field of medicine that influenced Doyle in writing this story. Who might have been his model for the scientist Lowenstein, and what was the nature of the “serum” he was dispensing?

An interesting chapter in the history of medicine lies at the heart of this story. It began on June 1, 1889, at a meeting of the Sociéte de Biologie in Paris. Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard3 stood before an audience of mostly elderly men; the average age of the members of the Sociéte was seventy-one. Before beginning his formal presentation, he put aside his notes and told his audience: “I am 72. My natural vigor has declined in the last 10 years and . . .” Brown-Séquard, a man of 6-foot 4-inches, began to describe his latest self-experiment:

“Last May 15 with the assistance of MM. d’Arsonval and Henoque, I removed one of the testicles of a very vigorous 2-3-year-old dog. After cutting the entire organ into little pieces, I put them into a mortar, adding a little water . . . then mashed the pieces to obtain as much juice as possible. After adding more water. . . I poured (it all) into an excellent filter paper. The filtering proceeded slowly . . . and four and-a-half cubic centimeters of a rather transparent pink liquid was collected.”

In reporting the results, he explained:

“The injections were quite painful, causing a red inflammation of tissues, insomnia and ‘violent’ dolor. Before May 15, the day of my first injection, I was so weak I always had to sit down after standing for a half-hours work. The following day and even more so afterwords, a radical change came over me and I . . . recovered at least all the strength I had possessed many years ago. A great deal of laboratory work hardly tired me at all.”4

He reported being able to resume his habit of running up and down stairs and working three or four hours after dinner. Through the use of a “dynamometer” and an “ergograph” he demonstrated that his strength had increased considerably.

With hindsight, several concerns arise when we read this account. The sterility of the preparation and the immediate, alarming side effects at the site of injection can be understood as an immune response to the injection of foreign protein. By today’s standards this experiment was without controls and would be highly ill-advised.

The public’s response was electric. Le Matin dubbed it Methode Sequardienne and opened a subscription to found an institute of rejuvenation. The findings were published in The Lancet and notoriety spread throughout Europe and to America. Three weeks after Brown-Séquard’s first communication on the testicular extract, the British Medical Journal published an article titled “The Pentacle of Rejuvenation.” Included were the opinions of two French physicians indicating that the claims of Brown-Séquard would have to be “rigidly tested.”5 In Germany and Austria, his claims were characterized as a “senile aberration” and “proof of the necessity of retiring professors who have attained their threescore and ten years.”

It was reported that following Brown-Sequard’s announcement, similar extracts had been administered by more than 12,000 physicians, reflecting a “cottage industry” that developed offering the Brown-Séquard elixir (Seguarine) to the general public. To counter unscrupulous activities, “Brown-Sequard and his assistant, D’Arsonval, prepared extracts to their own specifications and distributed it gratis to physicians willing to test and report the potency and effect of this preparation on their patients.”6 Subsequent researchers who followed Séquard’s methods precisely were never able to reproduce his findings. It has been shown that the testes contain little male hormone and that as soon as the molecule is synthesized, it is released into the bloodstream. It was only later that the first androgens were isolated from the urine. In short, Séquard was describing a placebo effect.

His claims gave rise to generations of colorful quacks and outright charlatans in both Europe and the United States. On the other hand, “in disproving the Brown-Séquard claims, the scientific basis of androgen physiology was laid.” The case is therefore made that the date of his presentation marked the birth of the field of endocrinology.7

Between out-and-out charlatans and scientists who were the pioneers in the field of endocrine physiology, there are a group of physicians whose work would have been known to Conan Doyle at the time he wrote “The Adventure of The Creeping Man.” These men (of course they were all men) sought “rejuvenation” through “organotherapy”: specifically, testicular implantation. They began their careers as serious physician/scientists but often succumbed to public pressure and acclaim.

A complete discussion of physicians who were active in this field is beyond the scope of this paper, but mention of a few whose work Conan Doyle may have known is appropriate. For a complete account of early attempts at rejuvenation through “organotherapy,” the author recommends The Gland illusion by John B. Nanninga, M.D.8

Of the surgeons attempting to rejuvenate patients through testicular transplantation, one of the most colorful was the Russian émigré Serge Voronoff (1866-1951). Voronoff based his belief in the value of testicular implants on his observations of eunuchs he had seen while working in the Royal Court of Egypt. He was impressed that they exhibited a lassitude that he attributed to premature senescence. He experimented with testicular tissue implantation on aging livestock (horses and sheep). Finding that they exhibited a restoration of physical and behavioral characteristics of younger animals, he then proceeded to graft testicular tissue from monkeys and chimpanzees into men. In the 1920s, Voronoff continued testicular transplants using primate glands at his private clinic in Paris. When his third wife, Louise Ignatiff, sued for divorce claiming abandonment, she accused Voronoff of spending most of his time at a miniature jungle and monkey colony near Cannes.9 He also performed the operation on his older brother George Voronoff, age sixty-five, publishing photographs taken before and four years after the surgery in The Sources of Life (1943). Voronoff was satirized in a novel by Bertram Gayton, The Gland Stealers, published in 1922. It is a story about a group of wealthy elderly men who go to Africa to capture one hundred gorillas and take their “glands” (testicles) for transplantation. The use of primate tissue certainly makes Voronoff a candidate for “Lowenstein of Prague” in Conan Doyle’s “Creeping Man.”

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes (Vol. II) edited by Leslie S. Klinger suggests that the model for Lowenstein of Prague might have been Eugene Steinach (1861-1944).10 The source for this conjecture is an article by J.C. Prager and Albert Silverstein that appeared in the Baker Street Journal.11 As Steinach did not promote the implantation of primate tissue into men, he seems an unlikely model from Conan Doyle’s story. Professor Eugene Steinach, a well-respected physiologist at the Viennese Academy of Science, focused his research on the effect of internal secretions from the testicles and ovaries on animal behavior. His work led him to the observation that ligation of the seminiferous tubules caused a decrease in sperm-producing cells (spermatocytes) and an increase in interstitial cells believed to secrete male hormone. In collaboration with a urologist in Vienna, Peter Lichtenstern, they began performing ligation of the vas deferens on a series of men aimed at rejuvenation. The subjective response to these operations was very encouraging and led to surgeons in Berlin, Switzerland, and the United States offering the “Steinach Operation” to their patients. Ultimately the therapeutic value of the procedure as a means of rejuvenation was discredited by the work of Robert Oslund at the University of Chicago in the 1920s. Sigmund Freud (1923) and William Butler Yeats (1935) both underwent the procedure and are often cited in the literature.12 They are among the hundreds of patients who were “Steinached.”

In closing, a few observations relating to other medical aspects in this story are in order. Conan Doyle’s choice of a name for the professor is interesting, “Presbury.” The name brings to mind the Greek word used in medical terminology, presbys, meaning or pertaining to old age. As an ophthalmologist, Conan Doyle would have used the term presbyopia referring to the loss of accommodation (near vision) with age. Similarly, we have presbycusis, the loss of hearing with age. Holmes asks Watson what he makes of Bennett’s sighting of the professor’s nocturnal appearance, creeping “on his hands and feet with his face sunk between his hands.”

The good doctor replies: “Speaking as a medical man, it appears to be a case for an alienist.” He is referring to a psychiatrist, from the French term aliéné meaning insane.

We may wonder what view Conan Doyle held on medical rejuvenescence. Dr. Watson believes that by identifying Lowenstein of Prague they have “traced the evil to its source.” Holmes agrees, indicating he intends to write Lowenstein that he holds him “criminally responsible for the poisons which he circulates.” But Sir Arthur gives Sherlock Holmes the last word. Holmes identifies the real source as the “untimely love affair which gave our impetuous Professor the idea that . . . he could turn himself into a younger man. When one tries to rise above Nature one is liable to fall below it.”

End notes

- From the G. Schirmer Collection of Opera Librettos, English Version by Ruth and Thomas Martin, G. Schirmer, Inc.

- Camford is a fusion of Cambridge and Oxford.

- For a review of the life and work of Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard see the article by Chris Gilleard, in Hektoen International, Spring 2015, https://hekint.org/2017/01/29/charles-edouard-brown-sequard/. C.E. Brown-Séquard is best known today for his experimental and clinical work on spinal cord injury. The Brown-Séguard syndrome refers to ipsilateral (same side) flaccid paralysis with impairment of touch, position and vibratory sense combined with contralateral loss of pain and temperature due to sectioning of one half of the spinal cord. Inconsistency exists in the spelling of his name: Charles-Edouard/Edward Brown-Sequard/Séquard.

- The quotations are from that can be found in at article by Jean D. Wilson, Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard and the Centennial of Endocrinology, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 71 (6), 1403-1409, 1990.

- “The Pentacle of Rejuvenation,” Brit. Med. J. Volume I (June 22, 1889, p. 1416.

- Arnold Kahn, Regaining Lost Youth: The Controversial and Colorful Beginning of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Aging, Journal of Gerontology: BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, 60A (2), 142-147, 2005.

- Jean D. Wilson, Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard and the Centennial of Endocrinology, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 71 (6), 1403-1409, 1990.

- John B. Nanninga, M.D. The Gland Illusion: Early Attempts at Rejuvenation Therapy, McFarland & Company, Inc. Jefferson, North Carolina, 2017.

- Idib., Nanninga, Chapter 5, p. 73. Also “Wife Sues Voronoff,” New York Times, February 26, 1928.

- The new Annotated Sherlock Holmes, edited by Leslie S. Klinger, Volume II, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc 2005, p. 1662.

- Prager, J.C. and Albert Silverstein, “Lowenstein of Prague: The Most Maligned man in the Canon.,” Baker Street Journal 23 (4): 220-227, December 1973.

- Idib., Nanninga, Chapter 6 Dr. Eugene Steinach and Vasectomy.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Fall 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply