Scott D. Vander Ploeg

Cocoa Beach, Florida, United States

|

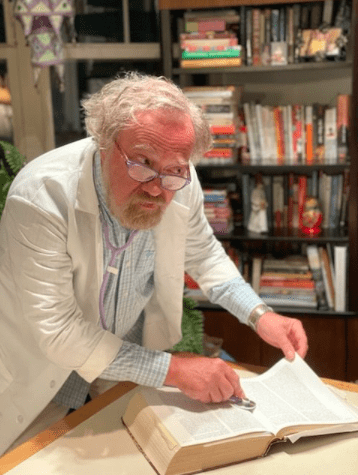

| Dr. Vander Ploeg (Ph.D.) checks the lit pressure of the complete works of William Shakespeare published in The Riverside Shakespeare. Photo by Audrey Kon. Courtesy of the author. |

I taught English courses for thirty years at a community college in western Kentucky. One of the more robust programs we offered was in nursing, and we also offered training for physical therapy assistants and respiratory therapists, grouped under the umbrella of “Allied Health”. We also had a med-tech program that had a small but steady enrollment. On the rare occasion, we even had pre-med students who were saving money and living at home for their first two years of college.

I was teaching in the “Humanities and Related Technologies” department. I advocated for general education and did not admire the technical programs. They were “terminal degrees” in that students could not use most of those credits to climb future educational ladders. As time went on, however, it became clear that I needed to embrace the ways that the humanities might be important to our medically-attuned students.

I created an Introduction to Literature course designed for students in medical practice of one sort or another. The course followed the standard course description, but substituted texts that were medically related instead of more generalized.

In general, English was not a high priority for most of these students, and I was dismayed to learn that nursing faculty encouraged the use of sentence fragments for charting, which is pretty much anathema to humanities faculty and especially to composition instructors. Moreover, in 1993 the Commonwealth of Kentucky Department of Education, supported by the state legislature, removed the arts and humanities from its annual school-age testing program, resulting in a precipitous drop in enrollment in humanities courses. The schools stopped bussing entire year-levels of students, elementary and high school, to our thousand-seat auditorium and arts center for theatrical, music, and dance programming.

A few years later, all of the colleges across the state merged with the local technical schools, further increasing the proportion of students whose need for humanities courses was diminished. At over 100,000 students, our community college enrollment numbers exceeded that of both the University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville combined. Departments like Nursing sought to reduce the required humanities credits in order to streamline their programs. The Arts and Humanities were in crisis.

Previously, we had offered two-semester surveys in American, British, and Western Literature, as well as Intro to Lit, sporadic creative writing, and a few oddball courses. After 1993, we could only get enrollment in Intro to Lit, often just one section per semester, maybe twenty students.

To entice more students to take an elective humanities course, I first approached the nursing staff with a pitch: what if there was a course that specialized in literature involving medical care, broadly construed? Wouldn’t it be a good idea to have students who are going into medicine review “the literature” that focuses on health issues? I pointed out that it would give their students a better understanding of the place of medicine in our culture, enhanced empathy, and would provide better appreciation for their role and the value of their studies. I hinted it could help in student retention. They could encourage their students to take my “Med Lit” course as one of their electives.

In the fall of 2017, I advertised the course. It began with some typical literary concepts. I liked to have students understand that interpretation of literature is not arbitrary and that there are traditions of approaches, different kinds of literary criticism, that can be applied. In the wonderful 1894 short story by Kate Chopin, “The Story of an Hour”, the news of a train wreck and the death of Louise’s husband, Brently, is gently told to her, and she grieves but begins to consider a life free of the social bonds of marriage, only to be surprised when Brently belatedly enters the front door. She dies of “a joy that kills,” according to the doctors, and we are left to ponder the ambiguities of the story.

There was not only a heightened understanding of the beauty of language and its complexity, but also some discussion of the heart issues involved. Was it a myocardial infarction, cutting off blood to the heart, or a stroke that affects the brain? What else might cause the heart to seize, atrial fibrillation, or something else? The author sets up the situation by making early reference to Louise’s heart condition, then provides a “gotcha” in the final line—the joy that kills. There was some debate as to whether that was a believable diagnosis, or if Louise was despondent in returning to married life after glimpsing freedom. It also raised questions about doctors in the antebellum era, and their attitudes toward women. The students were avid, arguing and questioning and realizing how the story was “so cool.”

We spent a few weeks looking at poetry from an anthology I had found, one specific to nursing and medicine. Issues related to depression and mania were treated in class, as well as euphoria and various excitations, some involving romantic entanglements. The class came to understand that mental and emotional issues are part of their field, and that literature was spot-on in portraying them as such.

Mid-semester was targeted for prose and fiction, and we toyed with Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar,” a weird tale in which a doctor of sorts puts a man under hypnosis as he is dying, and is then sustained or suspended in a kind of death sleep. The class was appropriately horrified at the ending, in which Poe imagines the character deliquescing into a puddle of goo when he is brought out of hypnosis. We talked about pseudoscience and the development of medicine, the power of the mind, and the use of placebos in clinical tests.

For a novel, I selected Still Alice, by Lisa Genova. The main character is a linguistics professor who begins to realize she is developing a case of early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. The class learned about what a novel does and what it aims toward, as well as how a family deals with the mother’s increasing tendency to be lost.

That same year, by lucky coincidence, the college had chosen a recent non-fiction work on late-life decisions—On Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande. This focused us on elder care and questioned the continued use of all of the technology and science we can muster, versus the choice of hospice and do-not-resuscitate orders.

Toward the end of the semester, we read Margaret Edson’s play, Wit, and watched a video of the made-for-tv movie version. The story involves a professor of English literature, played by Emma Thompson, who is a John Donne specialist. The class was a little familiar with Donne’s poetry from earlier in the semester. He often referenced his own illnesses, such as in the poem “A Fever,” or other maladies such as syphilis in “The Apparition.” The Wit professor is ill with cancer, and reviews her career as a tough and demanding professor. Her cancer progresses and she is visited by one of the professors who taught her—learning about compassion and the truth of Donne’s words in a way she had not understood before.

The class did not know that I, too, am a Donne scholar, a charter member of The John Donne Society. My dissertation on Donne’s poetry ran to 340 pages. I was also on good terms with a Donne expert named Kate Frost, who asked me to take over chairing a Donne session at a medieval-and-more conference, because her own fight with cancer had made it too difficult for her to continue. When I told them this, the class looked at me in shock. “You mean this really happened?” they asked. I told them that life aspires to become art, or maybe vice versa.

Teachers and learning figured into many of the literary works. It turned out that not just medical students enrolled, but several education majors did, too. When I learned that, I shifted emphases to include other subjects. I had not fully realized that literature is so rich and inclusive of all human attributes, that finding an emphasis in content was really no problem at all. Many other works could have and perhaps should have been included, but there are only so many weeks to a semester, and the students had other “lesser” courses they were taking, ones in which their focus was on subjects like anatomy and physiology, organic chemistry, and calculus. In any case, the literary works that involve medicine are quite fascinating.

SCOTT D. VANDER PLOEG is an early-retired professor of English/Humanities, named Kentucky college Teacher-Of-The-Year in 2009. His 1993 doctorate is in British Renaissance Lyric Poetry, though his range of study is more eclectic. He recorded essays for a regional NPR affiliate for a decade, and later wrote a column about the arts and letters for a small-town newspaper. He was the Executive Director of the Kentucky Philological Association, and a regular member of the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts. In his spare-time he is an amateur thespian, a jazz drummer, and a Sifu in Tai Chi.

Leave a Reply