Rebecca Grossman-Kahn

Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

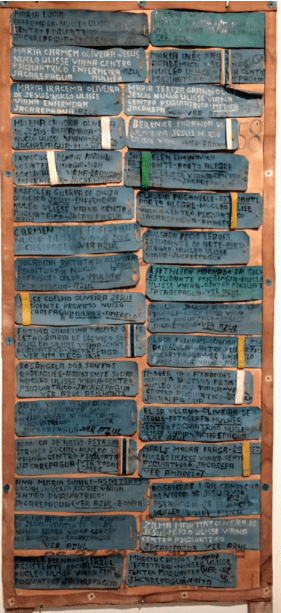

In a sprawling, cavernous art museum in Buenos Aires, I turned a corner and my eye caught on what appeared to be, from across the room, cardboard. As I walked closer to the display, I saw a large brown rectangle plastered with smaller blue rectangles in two rows. Each blue rectangle was filled with handwritten text in all capital letters. The piece was mesmerizing in its simultaneous display of order and slight disarray. The rows do not quite line up, and the text seemed squished into each rectangle, its color changing abruptly from white to black. Small, colorful, vertical lines are scattered throughout the blue pieces. Only when I look more closely do I see the words are not written with ink; they have been embroidered. I learn from a small plaque nearby that the artist was named Arthur Bispo do Rosário, and he made the pieces while living in a psychiatric facility in Brazil. The exhibit had curated a handful of pieces but included just a few sentences about Bispo do Rosário and his life. The longer I stood before his pieces, the more I noticed (an unusual button, a stamped “58” in a corner—perhaps a year?), and the more I wanted to learn about the person behind the work.

Arthur Bispo do Rosário was born in 1911 in northeastern Brazil. As a young adult he completed a short stint in the Brazilian navy, and later pursued jobs as a professional boxer and a domestic worker.1 At age twenty-nine, he developed the belief that he was a messenger from God. He arrived at a monastery and announced he was the messiah.2 Shortly thereafter he was arrested for public disturbance while sharing the news of his religious mission and brought to a hospital where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was transferred to a psychiatric residential institution where he resided until his death at age seventy-eight.

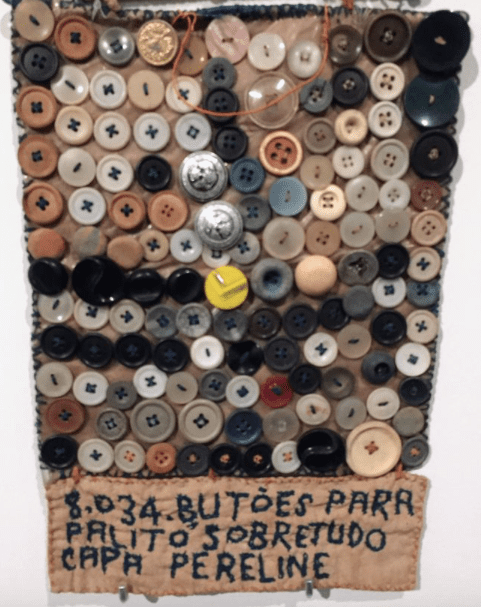

While his physicians saw a mind unraveling, Bispo do Rosário began unraveling his sheets and pajamas, collecting spools of blue thread. He started wrapping objects in the blue thread and later used it to embroider.2 His art was composed of found objects: discarded papers, cardstock, hospital utensils, collections of buttons, rubber boots, and other items he found around the hospital grounds. He developed a delusion that he had a spiritual mandate to document the world and its objects, which he would present to God on Judgment Day.1 Thus he assembled collections of items like rubber sandals and tin cans, and painstakingly wrote lists of names of people he knew. In the museum I saw a flag plastered with round buttons of many colors and textures, with a subtitle explaining their use: “buttons for cardigan overcoat.” They are grouped by color, imperfectly, pearly white and wooden tan buttons giving way to greens and deep navy. Like the cardboard rectangles, I am drawn to the mix of soothing repetition; the buttons are seemingly scattered randomly, yet subtle patterns appeared if I examined it closely.

Bispo do Rosário created 804 pieces throughout his life. His first exhibition was in 1982 in Rio de Janeiro, when he was seventy-one years old. A documentary filmmaker was sent to the psychiatric institute where he lived to document the living conditions, and instead created a film about Bispo do Rosário.3 This exposure led to his work being displayed in the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art, and later in the 1995 Venice Biennial. While Bispo do Rosário’s work has garnered considerable recognition in Brazil and even celebration at global art exhibitions, relatively little has been written about him outside of his home country. The medical literature includes just two English-language articles about his work and its relationship to mental illness.

Illnesses causing psychosis compel us to reflect on the notion of reality. Delusions may defy expectations of gravity, order, time, and physics. Psychiatric assessments observe for disorganization of language or behavior when evaluating for psychosis. Modern art may similarly topple expectations, rebelling against faithful depictions of the world.

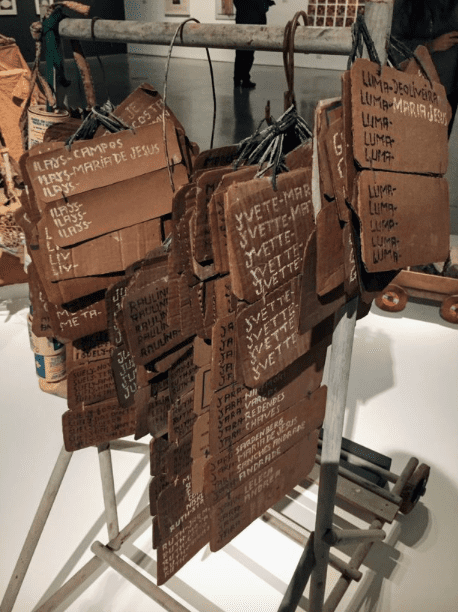

One of the pieces I found myself snapping photos of in Buenos Aires was a metal and wood rack, like one that might be used for storing clothing behind the scenes of a fashion show. Attached are cardboard signs draped over metal hangers. On the signs are repeating names in bright embroidery that looks like White-Out ink. To an observer, the words hold little meaning. They appear to be names of people: YVETTE-YVETTE-YVETTE-YVETTE reads one. The piece reminds me of a clothing rack, yet at the same time is completely unfamiliar. Is this sculpture a representation of an object in the world, or does it represent a break with reality—in essence, psychosis—in its form?

For Bispo do Rosário, it likely was one item in his large catalogue of the world to present upon his death for redemption. The artist’s circumstances and intention behind his work, not as art but as a sacred calling in the context of a delusion, change the very essence of the items.3 One may see Bispo do Rosário’s work as meticulous attempts to create order out of the disorganization of a mind in psychosis. His pieces are untitled and undated, as they were not intended for display. Bispo do Rosário told interviewers in no uncertain terms that what he made “had nothing to do” with art and was in fact “a registry” of the world.3 Some have even argued against displaying his work in museums, as it is counter to Bispo do Rosário’s own wishes and intention of his creations.3,4

Several years after I first saw Bispo do Rosário’s art, I became a psychiatry resident and I glimpsed creations in the hospital that reminded me of his work. One patient filled notebook after notebook with geometric diagrams, the pencil markings so deep and purposeful that the pages turn crinkly and textured from the graphite indenting each page. I saw a patient’s room with hundreds of papers, arranged just so across the floor, mattress, and windowsill. I stood on one bank of the river of papers, while the artist (patient?) stood on the other bank and explained his work. I saw a hospitalized man tear a piece of paper into hundreds of tiny pieces with irregular edges, and then carefully push the pieces into piles. He created mosaic outlines of shapes, a world of precarious sculptures on the drab gray carpet of the locked unit hallway.

The repeating patterns, the found materials, and the simplicity and complexity of grouped collections of items called Bispo do Rosário’s work to mind. These patients cast mundane, everyday objects like a blank piece of paper into new uses and forms. Just as psychosis sometimes causes the mind to latch on to invisible connections, creating meaning where others see none, this art creates meaning from what would otherwise be discarded. Yet these displays are often brushed aside by clinicians, interpreted more as evidence of disorganization than as art.

Much of what has been written about Bispo do Rosário irresponsibly blurs the thin line between madness and genius,5 such that the retelling of his story minimizes the tragedy of psychosis and sentimentalizes his unusual perspective. At the same time, recognition of the profound beauty and value in Bispo do Rosário’s work and that of other individuals experiencing mental illness may help reduce the pervasive societal stigma towards individuals with psychiatric conditions.6–8 In an unlikely twist, the grounds of Colônia Juliano Moreira, the psychiatric institute where Bispo do Rosário lived, now houses a museum and permanent collection of his work.9 Those who spoke with Bispo do Rosário during his life report he felt compelled to make the pieces,2 a far cry from a chosen vocation. Perhaps knowing Bispo do Rosário felt he had no choice in creating his pieces changes how they should be viewed: one may start to see the patterns in his work as meticulous obsession in repetition rather than meditative aesthetic choices. Expressions of appreciation for these creations must not minimize the suffering of psychosis and other mental illness. The life of Bispo do Rosário, including the legacy of his work, invites us to reflect on the nature of creations made in the midst of psychosis, and the role of creation and art in illness, treatment, and healing.

References

- Crippa JAS, Hallak JEC, de Carlo MMR do P. Arthur Bispo do Rosário (1909?-1989): insanity and art. The American journal of psychiatry. 2009;166(10). doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121830

- de Reymaeker C. The work of Arthur Bispo Do Rosário. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. Published online 2020. doi:10.1017/S204579602000013X

- Durão FA. Arthur bispo do rosário: The ruse of brazilian art. Wasafiri. 2015;30(2). doi:10.1080/02690055.2015.1011390

- de Oliveira S. Arthur Bispo do Rosario beyond the walls of the asylum. Psicologia USP. 2016;27(3). doi:10.1590/0103-656420130017

- Lima EMF de A, Lopez L. For a minor art: resonances between art, clinical practice and madness nowadays. Interface – Comunicação, Saúde, Educação. 2007;3(se). doi:10.1590/s1414-32832007000100028

- Yamauchi T, Takeshima T, Hirokawa S, Oba Y, Koh E. An Educational Program for Nursing and Social Work Students Using Artwork Created by People with Mental Health Problems. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2017;15(3). doi:10.1007/s11469-016-9716-9

- Galka SW, Perkins D v., Butler N, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward mental disorders before and after a psychiatric rotation. Academic Psychiatry. 2005;29(4). doi:10.1176/appi.ap.29.4.357

- Cutler JL, Harding KJ, Hutner LA, Cortland C, Graham MJ. Reducing medical students’ stigmatization of people with chronic mental illness: A field intervention at the “living museum” State Hospital art studio. Academic Psychiatry. 2012;36(3). doi:10.1176/appi.ap.10050081

- Museu Bispo do Rosario. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://museubispodorosario.com/

REBECCA GROSSMAN-KAHN, MD, is a Psychiatry resident at the University of Minnesota. Prior to medical school, she lived in Brazil on a Fulbright fellowship. Her professional interests include medical education, clinical ethics, and humanism in medicine. She has published essays in The Examined Life Journal, The New England Journal of Medicine, and The Intima.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Special Issue – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply