Philip R. Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

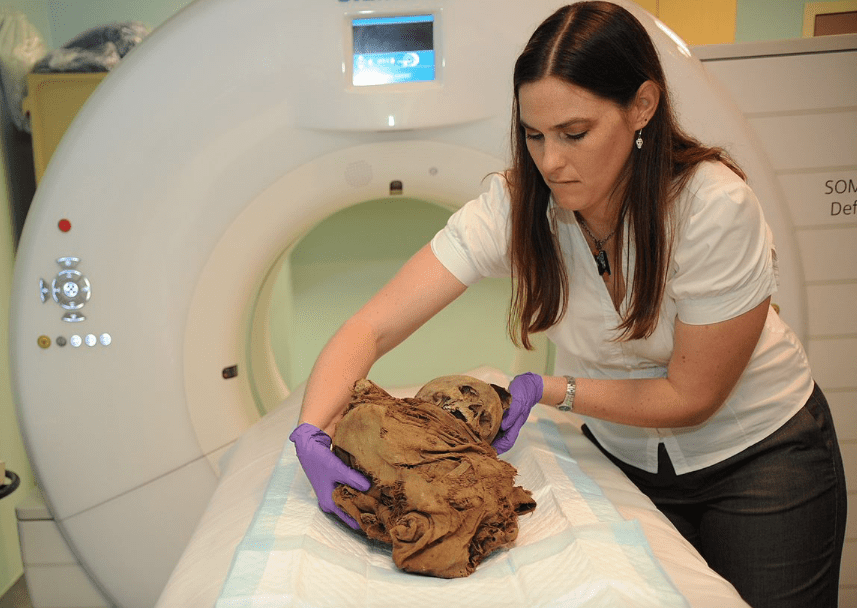

Paleopathology, the study of early animal and human artifacts, offers a historical perspective of disease and injury in the distant past. It uses skeletal and mummified remains as the substrate for this analysis. The discipline is about 200 years old and initially the analysis was based on abnormalities of structure without attribution to disease processes. These early analyses included deformations of human skulls. In the mid-nineteenth century, interest developed in the disease predecessors to syphilis, a condition thought to have appeared during the early Renaissance period. In the late nineteenth century, the term paleopathology was coined to describe pathologic findings in animal and human remains. The early twentieth century was focused on such artifacts as Egyptian mummies, Peruvian skulls, North American Indian skeletal remains, and animal remains by using statistical analysis of abnormalities. The evaluation of archeological dating caused difficulties in assessing the temporal development of disease patterns and analysis of bone structure. Additionally, early workers in the field were physicians without a background in archeology or archeologists without a background in human anatomy. Only in the late twentieth century were monographs published on diagnostic criteria and epidemiologic analysis.

A pioneer in the study of disease patterns in ancient populations was Dr. Arthur C. Aufderheide, a Minnesotan who lived until 2013. He completed medical school and a residency in pathology at the University of Minnesota. He became chair of pathology at several Minnesota institutions, including the medical school. He also studied ancient disease patterns using epidemiologic methods and participated in polar expeditions in the late 1960s, studying Arctic cultures of the Inuit.

In 1988, he helped to organize a symposium focused on the scientific discipline of paleopathology, problems of analysis that needed to be resolved, and possible future directions in research. Methodological concerns included disparities in terminology between published reports and inconsistent diagnostic criteria for skeletal analyses. The context of abnormalities within the general morbidity of an ancient population group during a particular time era was also of concern. Current attempts at reconstruction of behavior from analysis of the skeleton for evidence of disease and stress is still an important area of study.

Aufderheide’s studies with collaborators included an effort to establish the contribution of pneumonia as a cause of ancient deaths in the Andean coastal region of northern Chile, as well as problems in determination of skeletal lead burden in archaeological samples. This involved study of human bone lead content, which has been demonstrated to be related to socioeconomic status, occupation, and other social and environmental correlates. Skeletal tissue samples from an early nineteenth-century Philadelphia cemetery (First African Baptist Church) were studied by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry and X-ray fluorescence. Naturally mummified human bodies were examined by dissection and tissue chemical analysis for biomedical information. Even the globes of eyes were studied using rehydration in embalmed specimens. DNA analysis of fossils assessed the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Using this analysis of trypanosomes, Aufderheide and co-investigators found that Chagas disease was present as early as 9,000 years ago. Carbon-14 (14C) dating from mummies of 3,000 years ago in northern Chile confirmed that coca leaf chewing was an incipient practice among members of the population.

Other investigations by Aufderheide and his colleagues included mummification techniques in ancient Egypt, the stability of fatty acid ethyl esters in human hair by measurements of alcohol exposure in the hair of South American mummies, chemical dietary reconstruction of Greco-Roman mummies, and protein oxidation of a hair sample kept in Alaskan ice for 800–1,000 years.

The future of paleopathologic studies will lead to a better understanding of the lives of our ancestors and perhaps provide us with a confirmation of the precept: the more things change the more they stay the same.

PHILIP R. LIEBSON, MD, received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he served on the faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College since 1972 and held the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022

Leave a Reply