Philip R. Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

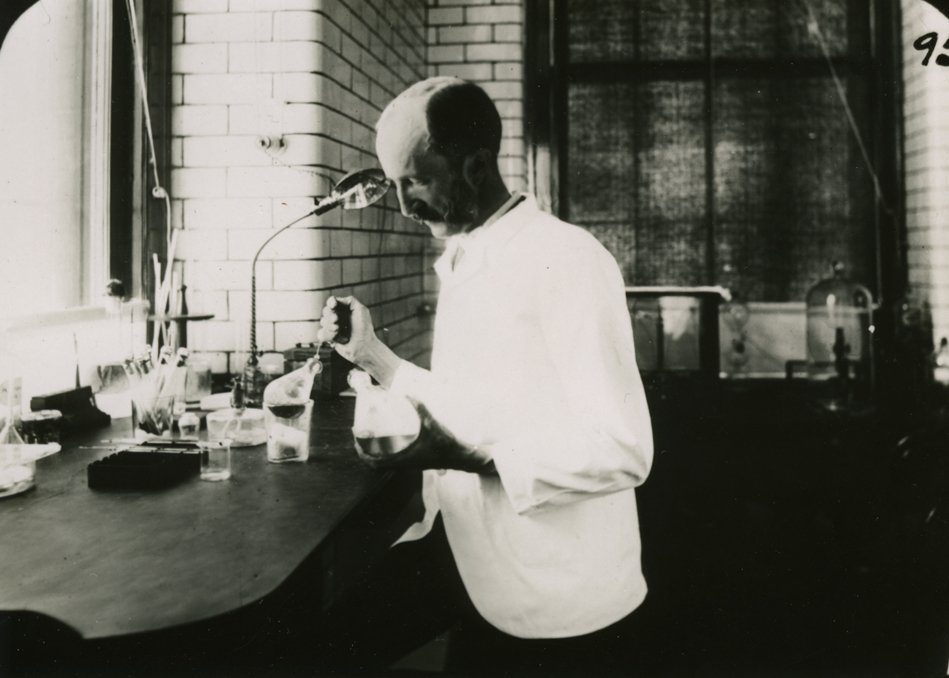

| Photo from the Adirondack Experience Museum. Circa 1895. |

Edward Livingston Trudeau was born in 1848, one year before Frédéric Chopin died of tuberculosis. Trudeau’s extended family eventually included Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada, and Garry Trudeau of Doonesbury fame. In his time tuberculosis was killing up to 14% of persons who had ever lived and about a quarter of adult Europeans. By the late nineteenth century, 70–90% of the urban populations of Europe and North America were infected with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and about 80% of those who developed active TB died of it. In 1849, the disease killed 490 per 100,000 white people and 520 per 100,000 black people. For comparison, the current total of 680,000 US deaths in a population of around 330,000,000 comes to 2 deaths per 100,000, and about half of that considering that the mortality covered most of two years. In the nineteenth century, tuberculosis was called consumption because of the wasting of the body and also the White Plague in comparison to the Black Plague because of the pallor in many of the patients.

Well known personalities who had developed or died of tuberculosis in the nineteenth century besides Chopin include Anne and Emily Bronte, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, John Keats, Guy de Maupassant, Walt Whitman, Stephen Foster, Napoleon II, Immanuel Kant, and René Laennec.

Edward Trudeau was no dispassionate observer. He himself developed a severe case of tuberculosis, his brother died of it as a young man, as did two of his children. It was perhaps the death of his older brother after three months of illness nursed by Edward that led Edward Trudeau to a career in medicine. However, he was born into a family of physicians in New York City and there was the strong possibility that this would have led him to a medical career anyway.

His strong French family background led him to spend his early education in France. After his older brother’s death from tuberculosis, Edward attended the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, graduating at age eighteen in 1871.

Joining a medical practice in New York City, he developed tuberculosis two years after graduation from Columbia. His physicians gave him six months to live. It was a precept in medicine at that time and even much later that if you had a major illness, a change of climate would be beneficial. For example, in the 1930s and 1940s, the noted Boston Cardiologist Dr. Samuel Levine would advise his heart disease patients to a sojourn in the South. A depressed Theodore Roosevelt traveled west to regain his equanimity after his wife and mother died on the same day. Trudeau’s change of climate was the Adirondacks at a hotel, and he regained his health temporarily. Note that he was not being treated with triple tuberculosis therapy, yet he survived ultimately to die of the disease half a century later. He therefore decided to live in Saranac Lake area with his family and establish a practice there.

In the early 1880’s he became acquainted with with the results of a Prussian physician’s experience in treating patients with a rest cure in cold clear mountain air. Trudeau was not averse to exposing himself and his patients to extremely cold temperatures on the assumption that the exposure to clear mountain air no matter the temperature was the approach to cure. Adequate rest and a healthy diet completed the armamentarium of that time’s triple therapy. Obtaining funds from local wealthy businessmen in the area, Trudeau founded the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium at Saranac Lake and a decade later the first US laboratory for study of tuberculosis which continues at present to study immune responses to infectious and other diseases. Although many of his patients were underprivileged, among his early patients at the Trudeau Institute was Robert Louis Stevenson, who in gratitude provided Trudeau with his complete works with appended verses.

When Trudeau learned of Koch’s discovery of the tubercle mycobacterium, he obtained a translation of Koch’s paper and developed a small laboratory to repeat Koch’s studies. He was able to grow the mycobacterium in a thermostat, the first time in the US, and proceeded to study the effects of tuberculin in producing immunity in animals. Unfortunately, an explosion in his ill-equipped laboratory caused it to burn down, but a friend and benefactor helped him build the first well equipped laboratory devoted to original research of tuberculosis in the US, the Trudeau Institute. One of the important results of the research was disproving claims of cures for tuberculosis primarily in Europe.

Nationally, Trudeau became president of the newly opened National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis in 1904, a predecessor of the American Lung Association. Later he became President of the Association of American Physicians.

After 1910, Trudeau’s illness became severe enough to prevent him from attending national conferences and personally receiving academic awards. Trudeau died in 1915 and the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium was changed to Trudeau Sanatorium and continued until 1954 when effective antibiotic treatments superseded the earlier triple therapy of mountain air, rest, and a healthy diet. During that time, a school was established there to train health care professionals in tuberculosis treatment methods. The Trudeau Institute’s name remained for the research and training center for health professionals.

Of the thousands of patients in the sanatorium noted ones included Bela Bartok, Irving Fisher, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, Manuel Quezon, Branch Rickey, and Christy Mathewson. Mathewson, the outstanding New York Giants pitcher in the first two decades of the twentieth century spent his last year at Saranac taking the cure and driving with his wife around the roads of Saranac until he died in 1925. Coincidentally, one of the last patients in 1954 was Larry Doyle, the Giants’ great second baseman and Mathewson’s teammate whose motto was “It’s great to be young and a Giant.”

PHILIP R. LIEBSON, MD, received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he served on the faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College since 1972 and held the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply