Florence Gelo

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

|

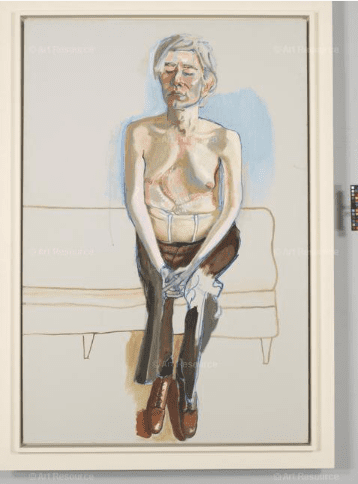

| Andy Warhol, 1970. By Alice Neel. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Timothy Collins. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY |

I project an image of the painting, Andy Warhol, on the screen in the medical school classroom. I am quiet for a minute. I then invite students to look at the painting and compose a list of what they see. Twelve students are present. Five minutes later, I notice four or five students writing, others gazing at the screen and a few flinching, and one student leaning towards another student and laughing nervously. I stand at the side of the classroom and ask, “What do you see?”

The discussion was slow to start. One female student remarked, “I feel embarrassed for him.” Two first year male students said: “He looks really sick” and “Not pretty to look at.” Others commented: “I wouldn’t stop to look at this,” “Makes me depressed,” “He looks deranged, and it makes me feel uncomfortable,” “I think he is lonely.”

This image is one of many by artist Alice Neel that I have chosen to include in an elective course designed for medical students, Learning About Implicit Bias by Looking at Art. The course aims to examine the not so benign attitudes and emotions present in the lives of our students, to increase self-awareness and awareness of those victimized by systemic forms of bias and prejudice. It is designed to make students squirm, to slow down, to look, to think and feel and to become comfortable with discomfort. Students are urged to step out of their comfort zone and uncover the assumptions and biases shaping their own attitudes and values, to witness their own thoughts and feelings.

Alice Neel’s painting of Andy Warhol, (1970) can help expose personal bias by urging students to look closely and name what they see, what is difficult to see, and what makes it difficult. In our culture, a man should pose as muscular, strong, self-confident and not appear “feminine.” In this image, Warhol appears self-conscious, vulnerable, feminine in a slightly gender-ambiguous way. Viewers will not find the brand of masculinity that most expect and prefer.

Neel, a social realist painter, called herself a “collector of souls” who portrayed her friends, family, and lovers. Her models included those from every class, race, and gender, from pregnant women nudes, family members, poet and writer Frank O’Hara, and James Farmer, the civil rights leader. Her images were never idealized. Four years before her death at age eighty-four, Neel used the same candid brush and painted a nude self-portrait, a bold portrayal of her aged body as a woman painter with paint brush in hand.

“Neel’s earliest subjects [show] her singularly uncompromising style. Often posing her subjects nude in a frontal position with limbs boldly outlined, occasionally distorted for effect, they dare us not to look away. The total effect of this decisive, unsentimental treatment of our shared imperfections is daunting and unforgettable.”1 Neel said, “One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle.”2

Neel’s subjects are painfully human and provoke responses that can make a student more knowledgeable about themselves and other people. In medical practice, many diverse patients will arrive, and medical students will need to be mindful during frenzied situations. When delivering patient care, time pressures often result in the clinical aspects of medicine taking priority over the humanistic. The more overwhelming the task of caring, the more inadequate a student may feel. They are expected to be competent and compassionate at the same time. Often, without warning, they must manage their unanticipated biased thoughts and feelings toward their patients. It is in this “hot” time-pressured environment that students must learn to find balance and recognize their own implicit biases.

As students view a Neel portrait, they allow themselves to experience the heat of personal discomfort, then name and confront it. In doing so, they discover and embrace their own and others’ humanity.

Ultimately, this course teaches humility, a cultivated willingness to respect and affirm the intrinsic value of another human being. Humility allows a student to value feedback, embrace experiences that uncover their own vulnerability, and be open to the wisdom and compassion of others.

End notes

- Sandra Bertrand, “Alice Neel — a Collector of SOULS – at the Met,” Photography & Art, Highbrow Magazine, May 24, 2021, https://www.highbrowmagazine.com/12089-alice-neel-collector-souls-met.

- They Are Their Own Gifts, directed by Lucille Rhodes, Margaret Murphy (1978); New York, NY: Women Make Movies, 1978, 16mm/DVD.

FLORENCE GELO, D.Min, NCPsyA, is a medical humanities and behavioral science educator. She directed and produced “The HeART of Empathy: Using the Visual Arts in Medical Education,” and uses the visual arts as a teaching tool to enhance clinical skills. She has published articles about illness, death, and dying.

Leave a Reply