Philip R. Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

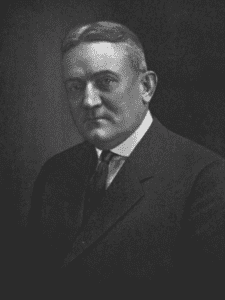

| Portrait of Henry Andrews Cotton from Appleton’s Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1924. Via Wikimedia. |

Over the centuries there has been a surfeit of talented medical quacks in all parts of the world. The word “quack,” indeed, is derived from the archaic Dutch word “quacksalver,” meaning “boaster who applies a salve.” A closely associated German word, “Quacksalber,” means “questionable salesperson.” In medical parlance it means a person who claims he has knowledge he does not have. Bordering on quackery was the promotion in the nineteenth century of patent medicines that clearly offered no benefit. Also, for many years children were given a teaspoonful of cod liver oil without a scrap of evidence that it would decrease the incidence of influenza.

An example of the extent to which quackery could be pervasive even in the twentieth century was the case of Dr. John Brinkley (1885-1942), who became known as the “goat gland” doctor. He obtained his medical degree from a diploma mill, and then widely used goat testicle transplantation to cure impotence in humans. Despite his medical license for practice in Kansas being stripped, he ran for and almost won the governorship of that state. He ran several hospitals and had a powerful radio station at the Mexican border where he could broadcast across a large area of the southwestern United States.

It was in psychiatry that quackery has been most easy, because until recently treatments were neither effective nor based on scientific evidence. A classical example of this was Henry Cotton, superintendent of the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey from 1907 to 1930. He claimed that removing infected teeth from patients could cure their psychiatric conditions, which he believed were caused by infections. He claimed to have an 85% cure rate but his surgical mortality was at least 30%. He also attempted cures by removing tonsils, ovaries, and spleens. On a positive note, at least he did eliminate physical restraints. And he achieved international fame from his treatments and lectured widely.

Cotton was by no means a product of a diploma mill. He studied medicine at Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland with Adolf Meyer, a prominent psychiatrist and a leader in American psychiatry. Meyer himself, among other psychiatrists at the time, considered that focal infections may have some bearing on psychotic episodes. He had visited Cotton at the Trenton Psychiatric Clinic and in 1924 had one of his former students, Dr. Phyllis Greenacre, evaluate Cotton’s findings and techniques. She visited the clinic, had concerns about Cotton’s evaluations, and found the medical records unsatisfactory. When later patients and their families became concerned about these surgical treatments, this led to an investigation by the New Jersey Senate. Nevertheless, the hospital directors strongly supported Cotton. Even the New York Times reported in 1925 that eminent physicians praised the hospital as the most progressive institution in the world for treatment of the insane.

Cotton’s reputation grew so much among the wealthy and social elite that he opened a private hospital to treat the members of families who displayed evidence of psychiatric disorders. One of his patients was the daughter of Professor Irving Fisher, a prominent Yale economist whose judgment in other matters may have also been deficient in that he predicted the 1929 stock market crash would produce only transient adverse effects.

In the early 1930’s, Cotton’s surgical mortality rates, possibly as high as 45%, led to concerns by the New Jersey State Institution departments. By that time, Cotton had retired from directing the state hospital, although he continued directing his private hospital until his death in 1933 from a heart attack. His obituaries lauded his pioneer efforts to treat psychiatric conditions in mental hospitals.

Was Henry Cotton a charlatan? For a time even Adolf Meyer agreed in part with the concept that infection was a contributing cause to some psychoses. Yet even the high surgical mortality rates from his surgery should have convinced Cotton that he was causing more harm than good, a lesson that since his time has continued to be frequently been ignored.

References

- Cotton, Henry Andrews. American National Biography (anb.org)

- Freckelton, Ian. Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine. (Book review), Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2005, pp. 435-438.

- Trenton Psychiatric Hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (12): 1982. December 1, 1999.

- Khazan, Olga (October 22, 2014). “Pulling Teeth to Treat Mental Illness”. The Atlantic.

- Wessely, Simon (October 2009). “Surgery for the treatment of psychiatric illness: the need to test untested theories”. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 102 (10): 445–451.

PHILIP LIEBSON, MD, received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he served on the faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College since 1972 and held the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Summer 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply