Robert Craig

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

|

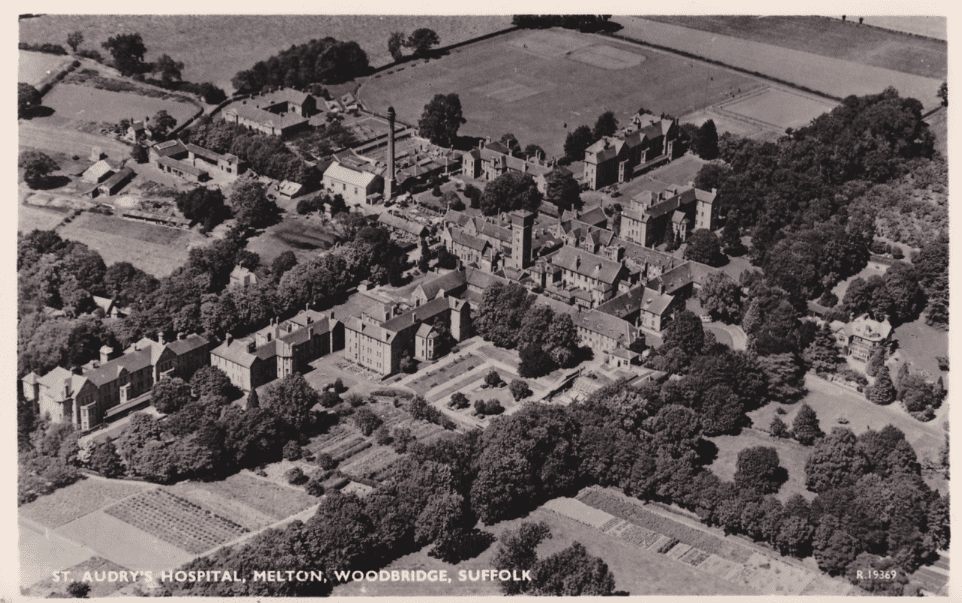

| The former St. Audry’s Hospital. Photo by Adrian S Pye. CC BY-SA 2.0. |

In 1964, having obtained a place to study medicine at Cambridge University, I was given the opportunity as a medical student to work as an assistant nurse for three months in a large residential mental hospital in Suffolk, England. The pay was meager but board and lodging were included. Suffolk was a poor county and reduced expenditure where it could. Mental Health Services were no exception. After 1948 the hospital came under the National Health Service, but funding was still less than generous.

This opportunity was hugely beneficial to me after a mostly private boarding school education. I gained exposure to everyday life before taking on the more privileged life of a medical student. It was a time of giving personal nursing care to a wide range of people, all of whom were deprived of liberty and living in an uncomfortable situation. The hospital was located in workhouse buildings that had been built in 1765. It became the County Asylum for Lunatics in 1827 and was renamed in 1916 as the Hospital for Mental Diseases.

The hospital housed 2,000 patients and employed many nurses and other health staff; psychiatrists, a medical officer, pharmacists, social workers, an anesthetist, a pathologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapists, and hairdresser and barber. Many others were needed to run this substantial estate as an almost self-sufficient enclave, including gardeners, engineers, builders, cooks, assistants, and apprentices. Facilities at the hospital trained these workers, including some who were patients.

Only the admission wards and acute wards maintained strict security, but all doors could be locked at night or if needed to contain patients who wandered. Male and female patients lived in separate wards and staffing for each retained this gender separation. There were no junior doctors, and the few psychiatrists and the medical officer maintained a low profile. The senior nurses ran the hospital while a secretary, treasurer, and a voluntary board with minimal support provided the administration. The hospital was near a small town, so transgenerational employment meant an almost closed society. The Chief Nursing Officer and Matron ruled. The two world wars had ended the previous period when doctors’ authority had been supreme and filled the gap before administrators controlled the increasingly bureaucratized health service.

A feature of the hospital’s design was the long, closed corridors for security. They connected the wards and other buildings but created a claustrophobic atmosphere. The wards all had a large day room separated from a dormitory of up to 100 closely packed beds, two central double rows and single rows at the sides, each with a small personal bedside cupboard. At the far end was the charge nurse’s (or sister’s) office flanked by four single rooms with fixed furniture, which served as seclusion and observation rooms. Off the dormitory was a large bathroom with three or four unscreened baths and many washbasins. Alongside the dayroom was a kitchen with steam-heated containers for the food that was delivered from a central kitchen and served by nurses in the dayroom. The meals were palatable and often staff ate the same food after the patients had been fed. Cutlery was boxed and counted on return to the kitchen. As another suicide-prevention measure, all windows were securely barred. Hospitalization has never prevented suicide attempts and, distressingly, the immediate weeks after discharge remain a dangerous time.

One of my jobs was to make fifty beds after breakfast with attention to neatness and regularity. Then I accompanied patients to occupational therapy or to work groups around the hospital, for which they received small sums of money. No government benefits were paid to hospitalized psychiatric patients. “No work, no pay” was the order of the day, so these jobs provided tobacco, toiletries, personal items, and clothing. Clothes were issued to patients who could not afford them, but lost items during laundering meant that most patients had ill-fitting clothing and appeared disheveled. Another of my work allocations was to play cribbage with an elderly man exempted through ill health. I quickly learned how to play and have enjoyed the game ever since.

Bathing and shaving were afternoon activities for those deemed unsafe to do this themselves, either because of incompetence or suicide risk. I was not informed about diagnoses, but florid psychosis, depression, and intellectual disability did not require much explanation. Bathing grown men, and especially shaving them with the added risk of scraping the skin (electric razors were not provided), made for a steep learning curve but also taught me the emotional closeness derived from personal contact.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was administered on the ward weekly for about a dozen patients by an anesthetist, resulting in modified seizures without mishap. I am sure that as in other places at this time, ECT was used too often, inappropriately, ineffectually, and often resulted in unnecessary memory loss. However, I have a lasting memory of witnessing a middle-aged farmer recover from severe melancholic depression after three treatments. I saw deep-sleep therapy carried out in an observation room. For three days, amobarbital was administered whenever signs of waking occurred. It was a last resort and probably less dangerous than insulin coma therapy, which was still occasionally used at a time when antidepressants were early in development. Paraldehyde with fruit juice, with its distinctive smell, was the usual sedative and given in shot glasses before dinner. This ritual was called “cocktail time” and was seemingly relished by the recipients, but I have never forgotten the smell. I have also not forgotten seeing how painful it was when given as an intramuscular injection, which was the usual method for out-of-control psychosis at the time of admission. The only antipsychotic agent available was chlorpromazine, which had only recently been introduced but was not available as an injection. I suspect the aversive effect of paraldehyde injection was probably in play as well.

|

| St. Audry’s Hospital. Source. |

Violence on the ward was uncommon but always a risk for both staff and patients. I was told on day one to NEVER to turn my back on a patient. In 1964, junior nurses were on the chronic wards for night duty. The wards were locked with no key provided to the on-duty nurse. Safety while calling for help by telephone was ensured by the protection offered by other patients. This proved the most successful conflict-reducing strategy.

Occupational therapy was a mainstay of treatment. The arts-and-crafts sections used qualified therapists. The industrial section took on outside orders for woodworking and such things as sock-making. The workshops and studio were run by craftsmen with nursing staff always available. Work provided a pattern to residents’ lives, increased self-esteem, and the token payment introduced a reward for effort. Most patients stayed for long periods in hospital and sometimes for life. Most long-stay residents were not visited by their relatives. Much later, I participated in a project to contact “lost” relatives and it was clear that they had often in the past been discouraged or were even refused permission to visit; but recontact was not always successful after long separation.

This experience was unforgettable. At the time, I decided that the job tended to make for highly eccentric psychiatrists and chose to take up general practice instead. But with many changes and various experiences after coming to Australia, when I was nearly fifty, I decided to train in psychiatry. The rotation included work in two psychiatric hospitals as well as acute mental health units. The two older hospitals were opened in the same era as Saint Audrey’s in Suffolk. I was constantly reminded of my earlier experience by staff and patients alike. Nostalgia can be misleading, but I wonder if we have been too quick to dismiss asylum as a valid therapy for chronic mental illness, especially if we consider what a difference extra financial support could make to a modern equivalent. The number of people with poorly or untreated serious mental disorders ending up in prison or homeless is clear evidence of an ongoing gap in our modern-day service provision.

ROBERT CRAIG, MA, MB, BChir, DObst.RCOG, MRCGP, FRACGP, worked for ten years in a UK rural general practice and two years as a government medical officer in the Solomon Islands. In 1984 he moved to Queensland, Australia, to join a family practice. After a few years he retrained to work in the psychiatric services, and before retiring in 2005, he was appointed as a clinician in the Queensland Centre for Intellectual and Developmental Disability in Brisbane. Since 2007 he has volunteered at the Marks Hirschfeld Medical Museum in Brisbane.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply