Andrew Wodrich

Washington DC, United States

|

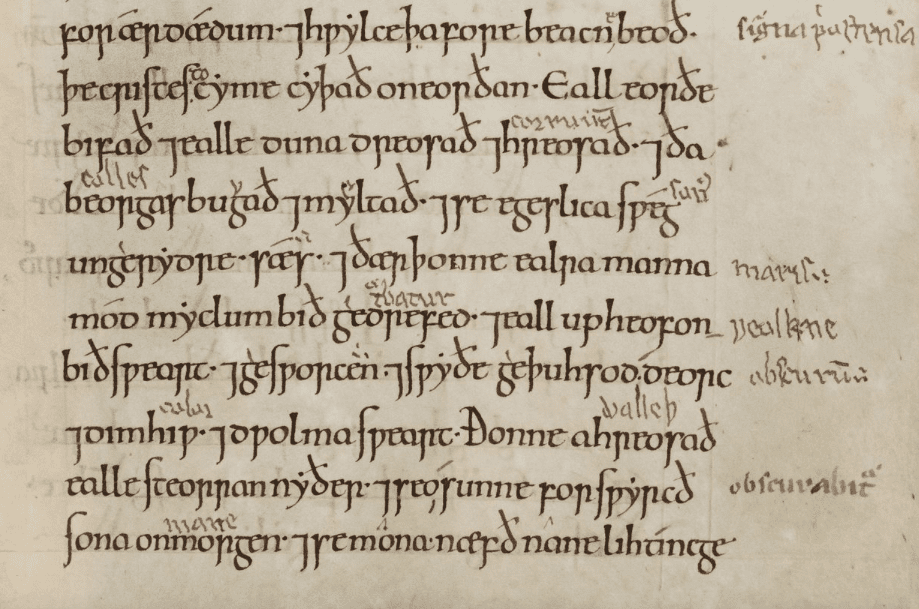

| Annotations and Glosses of the Tremulous Hand. An anonymous homily contained within Bodleian Library MS. Hatton 113, f. 68r – written approximately 1075 AD in Old English – shows the characteristic shaky script of the thirteenth-century scribe known as the Tremulous Hand. These additions are likely to have been made in the scribe’s later years as evidenced by the pronounced tremor that appears in his writing. Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford (CC BY-NC 4.0). |

Introduction

In the Middle Ages, before the ubiquity of the printing press, the act of writing and preserving the knowledge of Western Europe was promulgated primarily by monastic scribes.1 These scribes spent hours toiling away in dark rooms copying, translating, and authoring almost all of the written knowledge of their culture. The names and identities of these copyists and translators have been lost to history. However, one scribe’s work has been carefully preserved through an interesting feature of his writing: a pronounced tremor that makes his writing shaky and jerky. His birth name has not yet been discovered, but he is known to scholars as the Tremulous Hand.

The Tremulous Hand was most likely a monk at the Worcester Cathedral Priory in the English Midlands sometime in the early 1200s, a time when Middle English was spoken by all but the Norman nobles in England.2,3 At this time, one of the key duties of a monastery was the production of religious texts copied tediously by a dedicated group of skilled scribes. However, the Tremulous Hand’s infirmity likely precluded him from this occupation.2 Instead, he seems to have spent most of his time glossing and annotating manuscripts written in Old English; the Tremulous Hand’s glosses translated Old English words to their Middle English or Latin equivalents while his annotations highlighted passages of interest.3–5

A recent study conducted by a paleographer (someone who studies handwriting) and a neurologist concluded that the Tremulous Hand suffered from essential tremor on the basis of a regular and fine amplitude tremor, the absence of micrographia, and temporary tremor improvement, likely because of rest or alcohol ingestion—alcohol was regularly consumed throughout the day in the Middle Ages.6 Knowing that the Tremulous Hand suffered from essential tremor lends insight into who the Tremulous Hand was, which, in turn, can help glean more information about his life and historical context that could not be obtained through the words he wrote alone. For example, because modern neurology provides the insight that essential tremor worsens over time, the degeneration of the Tremulous Hand’s handwriting allows for a rough chronology to be established for his writings, an emergent property that is not afforded to the work of other contemporary scribes.7,8 The Tremulous Hand, in part because his easily identifiable script links him to work spanning more than twenty manuscripts, provides valuable emergent knowledge about the thirteenth century. Specifically, the distinguishable nature of his work contributes to the understanding of the transition from Old English to Middle English, the early linguistic study of Old English, and the renewed emphasis on priestly duties in thirteenth-century Catholic England.5

Emergent knowledge from the Tremulous Hand

Linking the numerous glosses found across manuscripts at the Worcester Cathedral to the Tremulous Hand provides knowledge about the period of transition from Old English to Middle English. The Tremulous Hand’s glosses, usually located in between lines of text, update Old English spellings or provide a direct word-for-word translation of the Old English into Latin or Middle English. His motivation seems to have been to improve the clarity of the Old English texts for fellow monks and priests more familiar with Latin or Middle English.7 This suggests that Old English texts were still being read as late as the thirteenth century, at least one hundred years after the language ceased to exist.9 Additionally, the need for glosses implies that the Old English language was not readily accessible to the average monk in the thirteenth century, but also not too challenging to read for those with sufficient skill.4,10 Indeed, even the Tremulous Hand in his later life appears to erase and correct earlier mistakes in translation; this implies that even he was not an expert in Old English when he began his work and that he learned Old English over the course of his career.7 The Tremulous Hand’s distinctive writing also facilitates comparisons with other contemporary scribes’ work. For example, one such comparison hints that medieval scribes knew how to write their own language according to a set of orthographic and grammatical rules and that this was a shared phenomenon amongst speakers of the vernacular.7,9 An interesting notion that arises from this comparison is that there may have been a school located in the English Midlands in the thirteenth century that taught scribes how to read and update Old English texts in a consistent manner.7

A number of pieces of evidence—all of which rely upon the identification of the Tremulous Hand’s glosses and annotations by his quivering script—point to the conclusion that the Tremulous Hand was committed to a systematic study of the Old English language. First, across more than twenty manuscripts, the Tremulous Hand made at least 100,000 glosses, annotations, and entries during his working career.10 Second, the Old English manuscript sections with the highest number of glosses per page are coincidentally those with known contemporary Latin translations housed in the Worcester Cathedral.4 This suggests that the Tremulous Hand was utilizing his religious Latin schooling to teach himself Old English by studying the Old English and Latin texts in a side-by-side fashion. Third, across multiple manuscripts, there are worksheets in the Tremulous Hand’s shaky script containing Old English-to-Latin word pairs arranged in alphabetical order of the Old English word, the first known instance of an English word-ordered glossary.4,9 Only by linking the word-pair lists across multiple manuscripts to the Tremulous Hand does the systematic nature by which he worked appear. In other terms, if the author or authors of a variety of word lists were indistinct, it would be challenging to argue that any one scribe made a systematic study of the Old English language. Lastly, the Tremulous Hand, in annotating heavily a passage lamenting the passing of Anglo-Saxon clerics who had translated religious texts in Old English, reveals his deep interest in the Old English language and provides a rationale for his systematic study of the language.5

The complete set of annotations made by the Tremulous Hand, which usually take the form of the Latin words nota, narration, or exemplum written in his distinguishing script, exposes a practical purpose of his work beyond a linguistic interest in Old English texts.3,5 These markers, a sign of his interest in a passage, provide valuable insight into changing patterns of religiosity in England following the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215. The Fourth Lateran Council, called by Pope Innocent III, placed a renewed emphasis on the spiritual obligations of the laity and the pastoral duties of the clergy.4,11 Interestingly, the Tremulous Hand, who likely lived shortly after the conclusion of the Council, preferentially annotated manuscript passages dealing with the duties of priests, sin and confession, and the sacraments, among others.5 This suggests that the Tremulous Hand had a particular interest in Old English passages that thematically overlapped with the central issues debated at the Fourth Lateran Council. Additionally, the focus of a cloistered monk on passages related to the pastoral care of the laity suggests that the Tremulous Hand may have been updating old texts for the benefit of parish priests seeking inspiration for their homilies and preaching.4 In this way, the Tremulous Hand may have been trying to unlock the knowledge contained within monastic texts for the benefit of the religious community at-large.4

Conclusion

The Tremulous Hand’s distinctive script, surely a handicap in his own time, has helped to set him apart from other contemporary scribes and preserve the connection of his authorial identity to his work. This, in turn, has helped scholars to uncover deep secrets about life in the Middle Ages that would be otherwise unrecoverable. The Tremulous Hand’s complete set of work, as identified by his degenerative penmanship, lends insight into how Old English transitioned into Middle English and how speakers of Middle English interacted with their ancestral language. Additionally, his shaky handwriting links his work together and reveals a monk deeply devoted to methodically investigating the Old English language centuries before the widespread study of the language during the 1500s.4 And, the Tremulous Hand’s unsteady marginal annotations give evidence of how monks assisted parish priests in their mission to better attend to the needs of the laity in thirteenth-century England. Through his infirmity, the Tremulous Hand’s scholarly contributions live on in a way that is bigger than he could have ever imagined.

References

- Lord V. The Medieval Scribe and the Art of Writing. UltimateHistoryProject.com. 2019:7-10. http://ultimatehistoryproject.com/the-medieval-scribe.html.

- O’Mara T. The Tremulous Hand of Worcester and the Transformation of the English Language. Worchester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog.

- Collier WEJ. “Englishness” and the Worcester Tremulous Hand. Leeds Stud English. 1995;26:35-47.

- Franzen C. The Tremulous Hand of Worcester: A Study of Old English in the Thirteenth Century. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1991.

- Collier WEJ. A Thirteenth-Century User of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Bull John RylandsUniv Libr Manchester. 1997;79:149-166.

- Thorpe DE, Alty JE. What type of tremor did the medieval ‘Tremulous Hand of Worcester’ have? Brain. 2015;138(10):3123-3127. doi:10.1093/brain/awv232.

- Franzen C. The Tremulous Hand of Worcester and the Nero Scribe of the “Ancrene Wisse.” Mediu Ævum. 2003;72(1):13-31.

- Liang T-W, Tarsy D. Essential Tremor: Clinical features and diagnosis. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer; 2020.

- Drout MDC, Kleinman S. Doing Philology 2: Something “Old,” Something “New”: Material philology and the recovery of the past. Heroic Age. 2010;(13).

- Schipper W. The Worcester Tremulous Scribe. J English Linguist. 1997;25(3):183-201.

- Wayno JM. Rethinking the fourth lateran council of 1215. Speculum. 2018;93(3):611-637. doi:10.1086/698122.

ANDREW P. K. WODRICH, BS, is a fifth-year MD/PhD candidate at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine currently pursuing a PhD in neuroscience at Georgetown University and the National Institutes of Health. Beyond his research interests in neurodegenerative diseases and brain aging, he is interested in the history of medicine and disease in medieval Europe.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply