Tonse N.K. Raju

Gaithersburg, Maryland, United States

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

In the opening sentence of his extraordinary masterpiece, Gabriel García Márquez distilled the recurring themes of One Hundred Years of Solitude1: the absurdity of death, the restorative power of memory, and the amazement of a discovery rolled into the eternal cycle of time. The omnipotent narrator begins in the present, telling us that “many years later” a condemned man would be facing a firing squad and remembers a seemingly trivial incidence: his discovery as a boy “that distant afternoon,” as he touched a large cube of ice, which his father would later say was “the great invention of our time.”

In this 417-page magnum opus [Fig 1], García Márquez weaves the stories of people’s lives in a Colombian village, Macondo, in a prose style now famous as magical realism. The main story chronicles six generations of the Buendías, dense as the tropical forests of Latin America and spanning more than one hundred years. Passionate love, ruthless betrayals, unreal magical events, brutal insurrections, and mindless battles amidst revolutionary fervors—are these real or fiction? One wonders.

A single episode1 that occurs early in the story invites a focus on contemporary sociopolitical significance: the struggles of the protagonist against the dual “plagues” of insomnia and amnesia, and the consequences of living in an alternate reality.

José Arcadio Buendía and his wife Úrsula offer shelter to Guaijiro Indian siblings Visitación and her brother. Both had fled a region stricken with the plague of amnesia. One day, Visitación warns the Buendías that her fatalistic heart has told her that the epidemic would follow her to the farthest corners of the earth. She, along with all in that household, would be affected by the plague. No one believes her.

A few weeks later, Jóse Arcadio finds himself unable to fall asleep. Yet, he feels no fatigue the next day. Soon all in that household become insomniacs, but they too do not worry since they never feel tired. When Úrsula sells her homemade candies in the village, the sickness spreads through those sweets and the whole village starts suffering from insomnia. Villagers spend days and nights doing nothing or playing silly games. Along the way, they forget how to dream. But being good citizens, they wish to prevent the sickness from spreading beyond their village. So, they place goat bells at the entrance to the village and ask visitors to ring them as they pass through Macondo to announce that they are uninfected outsiders.

Matters get worse when José Arcadio and his son Aureliano begin forgetting the names of familiar objects. To prevent loss of memory, they affix labels with the names of the objects: table, chair, clock, wall, bed, pan. But this is not enough and the loss of memory continues. They realize that soon they may forget what to do with those objects. So, they make more descriptive labels: This is the cow. She needs to be milked every morning . . . the milk should be boiled to be mixed with coffee. In this manner, they continue to live as the reality of life begins slipping away. In no time, however, the plague of amnesia affects all villagers. They, too, begin writing down the names of objects and their personal feelings, hoping not to see a day when they forget the value of written words and letters.

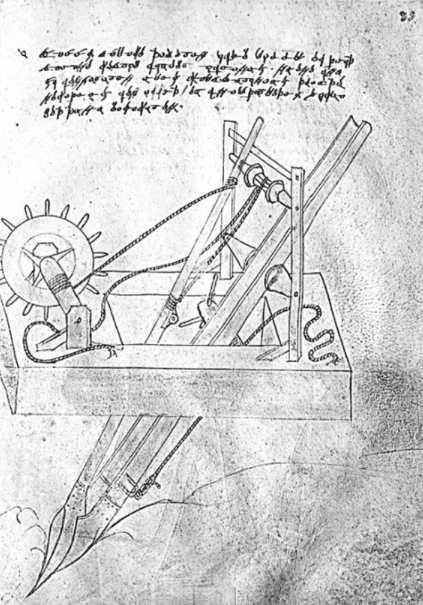

Defeated by all attempts to preserve memory, José Arcadio Buendía takes a dramatic new approach—building a memory machine, a spinning dictionary that could be operated by using a lever. With that machine, within a few hours the words and notions most necessary for life would pass in front of their eyes. He builds such a machine, writing almost fourteen thousand entries. Using it, every morning one could review the totality of knowledge acquired during a lifetime.

It was about that time that an elderly gypsy appeared at Buendía’s house. He was well-known in Macondo, but thinking he had died, the villagers had forgotten him. The gypsy quickly saw that his old friend José was suffering from amnesia. He pulled out a small bottle containing a liquid of “gentle color” and gave it to José to take a sip. A light goes on in his memory—he is no longer amnesic. In no time, the remedy is passed on to the entire village. They all joyfully celebrate the restoration of their memories.

The story provides a perspective about the human cost of insomnia and amnesia. It also offers implied perspectives on the socio-political consequences of these formidable “plagues.”

The people of Macondo did not feel exhausted despite being awake for days and weeks. Insomnia enabled them to finish the chores of daily living, but suddenly they found nothing else to do. Then they tried all kinds of tricks to fall asleep until the point of exhaustion—this was not from fatigue but because of their nostalgia for dreams. The inability to dream and enrich their lives was the heaviest price of insomnia.

But the price of amnesia was even higher. Individually, amnesia—the forgetting of self, surroundings, and childhood—became unbearable. The tragedy of personal memory loss was compounded when amnesia became an epidemic leading to the collective loss of memory, thereby forgetting history.

Memory and history are two sides of the same coin. Loss of historical memory and living in a world of alternate reality remind us of the oft-quoted George Santayana aphorism, which in its original form reads: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The dangers of societal amnesia include the perpetuation of false beliefs and a failure to avoid future tragedies. There are many examples of historical amnesia, but a few contemporary examples highlight the dangerous consequences of this malady: minimizing or denying the horrific tragedy of slavery and racism in the United States, the denials of the Holocaust, forgetting the devastation caused by infectious diseases2 such as smallpox, which killed more people in the twentieth century alone than all the combined wars and battles of that century, and the contemporary activism against all forms of immunizations and vaccinations.

The last component of the story with a medical perspective is the method the protagonist adapts to overcome the plague of amnesia. When all else fails, José Arcadio Buendía constructs a memory machine, a classic example of a mnemotechnic. Neuropsychologists have identified this phenomenon as synesthesia.3,4 This is a process of removing boundaries between two sensory pathways, enabling one of them to trigger the other sensation. Examples of synesthesia include artists seeing colors as they listen to music, the sensations of the smell and taste of food upon seeing cooking shows on TV, and visualizing the meaning of spoken words. José Arcadío’s memory machine, a sort of revolving dictionary, is based on synesthesia. In addition, his attempts to write down names and meanings is an example of the best process to preserve historical memories. García Márquez likely modeled the concept of the memory machine, a forerunner of modern computers, by adapting the inventions of the brilliant fifteenth-century Italian engineer Giovanni Fontana5 [Figures 2 and 3].

Did García Márquez intend for the readers of his stories to interpret them as described above? We can get a feeling for what he meant from his 1982 Nobel Prize speech titled The Solitude of Latin America.6 García Márquez says that the entire Latin American reality is far stranger than fiction because despite the independence they obtained from the Spaniards, it did not put the continent “beyond the reach of madness.” Nothing more needs to be added.

Just as the eldest son of José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula did, their second son, José Arcadio, also faces a firing squad because of his revolutionary activities. As the smoking mouths of the rifles are aimed at him, he thinks of his pregnant wife Rebeca and says to himself: “Oh, God damn it! I forgot to say that if it is a girl, they should name her Remedios.”

When the blood from the first bullet trickles down his thighs, he shouts, “Bastards!” as if to say, today I, tomorrow you.

References

- García Márquez, G. One Hundred Years of Solitude. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1967.

- Hostetter MK. What we don’t see. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1328-1334.

- Bolzoni L. The Play of Images. The Art of Memory from its Origins to the Seventeenth Century. In: Corsi P, ed. The Enchanted Loom: Chapters in the History of Neuroscience Vol Part 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991:16-165.

- Luria A. The Mind of Mnemonist: A Little Book about a Vast Memory. Cambridge, MASS: Harvard University Press; 1987.

- Fontana G. Bellicorum instrumentorum liber cum figuris. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. https://iiif.biblissima.fr/collections/manifest/3b360000d703cf66516dc5d4eb9cdf1aa7c713e8?tify={%22panX%22:0.588,%22panY%22:0.687,%22view%22:%22thumbnails%22,%22zoom%22:0.355}. Published 15th century. Accessed September 12, 2021.

- García Márquez, G. The Solitude of Latin America. The Nobel Foundation. The Nobel Speech Web site. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1982/marquez/lecture/. Published 1982. Accessed September 12, 2021.

TONSE N.K. RAJU, MD, studied pediatrics and neonatology at Cook County Hospital and the University of Illinois in Chicago, where he served as Professor of Pediatrics until 2002. He then joined the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. He is currently an Adjunct Professor of Pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University, and the Deputy Editor for the Journal of Perinatology. He has written medical history books titled The Nobel Chronicles (2002); The Importance of Having a Brain: Tales from the History of Medicine (2012); and six books of fiction. His works have received critical acclaim.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022