Gautam Sen

Kolkata, India

|

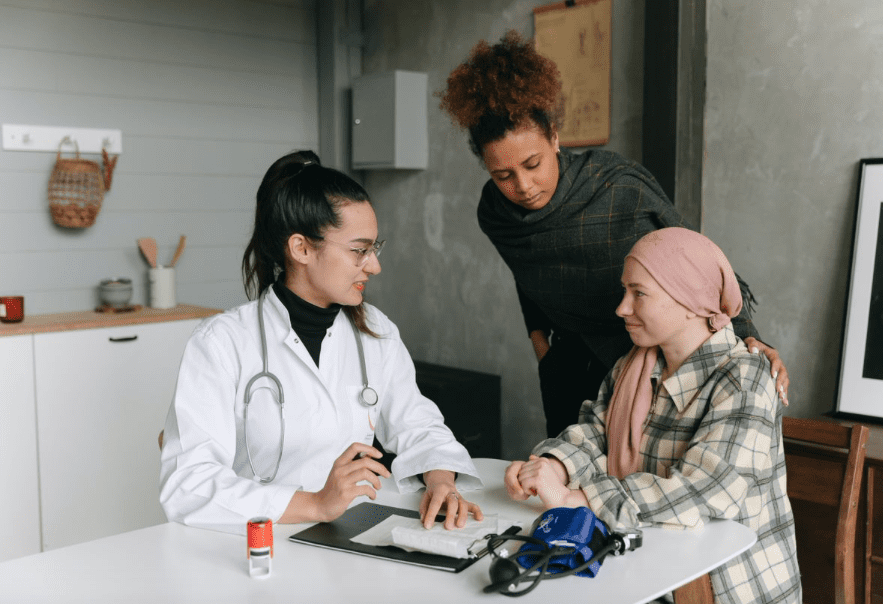

| Doctor-patient bonhomie is beneficial for both. Photo by Thirdman on Pexels. |

Imagine a hospitalized patient in the advanced stages of a difficult disease. He wonders whether he will survive and, if he does, in what state he will spend the remainder of his life. Alone in bed, he sometimes finds himself struggling with the meaning of life. He feels isolated, helpless, and lonely. What he would give for someone to talk to!

Nurses hover around him like ghosts. At some point one of them gives him medication or inserts a thermometer in his mouth. An overworked doctor pays him a three-minute visit, most of it engaged in looking at the medical chart. Perhaps he once glances at the patient over his glasses and asks, “So how are you doing today?”

No one is unfriendly or rude. Everybody goes about their assigned duty with a practiced, mundane professionalism. However, it is this very aloofness, not impolite but impersonal, that makes the patient feel like he is an item on a list that is attended to and ticked off at specified moments of the day. It shrinks him.

If the patient is lucky, he enjoys a short spell of meaningful human interaction during the hospital’s visiting hours, but otherwise he may as well be in a foreign land. Should he die in the hospital, it would hardly cause a ripple in the routine flow of activity. His people would be informed, his body sent to the morgue, another patient would occupy his bed, and everything would go on as before. The patient would seem to have never existed . . . but, of course, he did—there are still some bills that need to be cleared before his body is handed over.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that, in far too many places around the world, patients do not count for much: they are merely a means to an end.

But that is not the way medicine was ever supposed to be. “Wherever the art of Medicine is loved,” said Hippocrates, “there is also a love of Humanity.”1

It has been said that the good physician treats the disease, and the great physician the patient.2 The former there are aplenty; the latter are relatively rare. What sets them apart is their mindset: aware that each person has an inner as well as an outer self, they consider not only the physical aspects of their patient’s condition, but also the socioeconomic and spiritual milieu to which they belong. Consciously or unconsciously, they follow William Osler’s dictum: “Each person represents a story. That story includes their diseases, their new problem, their social situation, and their beliefs.”2 While knowing patients’ stories wins respect and confidence, having a deeper insight into the nature of an illness enables more effective care.

Spirituality is an important aspect of this holistic approach. Once associated with religion, it now has a broader connotation. The Collins English dictionary defines “spiritual” as “relating to people’s thoughts and beliefs, rather than to their bodies and physical surroundings.” The religious and the spiritual may or may not overlap. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that 25% of Americans identify themselves as spiritual but not religious, and according to the global research organization YouGov, one of Americans’ top New Year’s resolutions in 2020 was to be “more spiritual.”3

Being spiritual implies giving precedence to human dignity over material profit. Kindness, charity, and compassion, for instance, are spiritual attributes, but often do not fetch physical rewards. Giving food to the homeless out of empathy is spiritual behavior, whether one is a believer or not.

That said, spirituality may also well be tied to the search for life’s purpose, faith in God and the supernatural, and questions such as how we are related to the rest of creation and what happens to us when we pass on.

The World Health Organization has described spirituality as a core dimension of health that sustains people in times of distress, and a policy statement of the American Thoracic Society mentions the identification of patients’ spiritual needs as a core competency for critical care physicians.4 Unfortunately, the spiritual dimensions of medical care are ignored or underplayed in most medical schools, and as Michael and Tracy Balboni point out in their book Hostility Towards Hospitality: Spirituality and Professional Socialization within Medicine, modern medicine is, by and large, antagonistic toward the humanistic concerns that spirituality and religion represent.5

Thankfully, there is room for hope with the initiation of programs such as the 3 Wishes Project (3WP), which allows terminally ill people to die with dignity in the comforting presence of their loved ones. An excellent illustration of this is a young man named Adam, who was nearing death in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a US hospital. He had enjoyed the outdoors and was fascinated by sunsets, but now was confined to the dull, white-walled room of the ICU, where he was exposed to the continuous beeping of monitors and the grim sight of life-support machines. His wife wished her husband could die in a way more befitting his nature. Because this particular hospital had adopted the 3WP, it made all the necessary arrangements to move Adam’s bed to the hospital’s fourth-floor outdoor terrace. Here, with his wife lying next to him, the young man breathed his last as the sun began to disappear below the horizon.6

Who would not want to bid goodbye to a dying loved one in similarly beautiful circumstances? Of course, that is only possible if healthcare staff and administrators work hand-in-hand with patients and their loved ones in a spirit of giving. Such an act would enrich not only the final moments of the dying, but also the inner lives of all participants.

One potent way of bringing the spiritual lives of patients into sharp focus is by offering to take their spiritual history—a step that, according to surveys, a majority of patients would heartily welcome.7 This would especially apply to those suffering from life-threatening diseases, given the strong evidence that serious illness often heightens one’s spirituality.7 A cure may not be possible, but if people can be led to a peaceful acceptance of illness, that inner healing8 would help them transcend their physical condition.

In times of medical uncertainty, simple gestures such as allowing patients to express concerns, lending a sympathetic ear, talking to them, holding their hands, or even just touching them, might go a long way in assuaging anxiety.

The late superintendent of Norwich Hospital Dr. Morgan Martin observed, “Physicians dispense not only medicines, but words . . . that affect the patient more than the medicine.”9 Words and modes of behavior that acknowledge and celebrate patients’ inherent dignity work like spiritual manna. Hopefully, as time passes, the world of medicine will create more space for the feelings and inner lives of patients.

References

- Stone L, Gordon J. A is for aphorism – “Wherever the art of medicine is loved there is also a love of humanity.” Australian Family Physician. 2013;42(11):824-825. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24217108.

- Centor Robert M. To Be a Great Physician, You Must Understand the Whole Story. MedGenMed. Published March 26, 2007. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1924990/.

- Young R, Miller- Medzon K. Can spirituality exist without God? A growing number of Americans say yes. wbur. Published January 13, 2020. Accessed August 28, 2021. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2020/01/13/spirituality-krista-tippett.

- Swinton M, Giacomini M, Toledo F, et al. Experiences and Expressions of Spirituality at the End of Life in the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2017; Accessed August25, 2021.195(2):198-204. doi:10.1164/rccm.201606-1102oc.

- Balboni M, Balboni T. Do Spirituality and Medicine Go Together? Center for bioethics. Published June 1, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2021. https://bioethics.hms.harvard.edu/journal/spirituality-medicine.

- 3 Wishes Project brings dignity to dying patients. UCLA. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://newsroom.ucla.edu/stories/3-wishes-project-brings-dignity-to-dying-patients.

- Mueller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious Involvement, Spirituality, and Medicine: Implications for Clinical Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2001; Accessed August 26, 2021. 76(12):1225-1235. doi:10.4065/76.12.1225.

- Puchalski CM. The Role of Spirituality in Health Care. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 2001; Accessed August 24, 2021. 14(4):352-357. doi:10.1080/08998280.2001.11927788.

- Get Inspired by a Quote. Less is More Medicine. Accessed August 28, 2021. http://www.lessismoremedicine.com/quotes.

GAUTAM SEN, M.A. (English), B.Ed., TEFL, resides in Kolkata. He has authored fiction, non-fiction, and poetry books, and one of his stories features in Prizewinning Asian Fiction (Hong Kong University Press). His writings have appeared in U.S., British, Indian, and Hong Kong journals. His interest in spirituality in medicine stems from his first-hand experiences when his wife was ill.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply