Philip Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

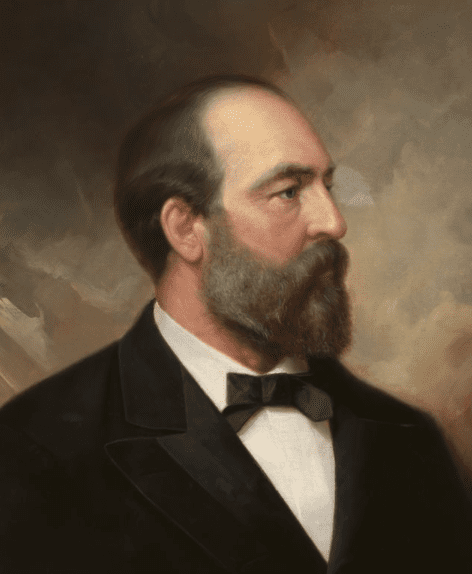

| James Abram Garfield. By Ole Peter Hansen Balling. 1881. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Public Domain. |

The medical treatment of some US presidents and ex-presidents has been controversial. One example is George Washington, who in 1799 at age sixty-seven suffered from an acute throat ailment that was treated by his physicians with molasses, vinegar, and butter gargles; inhaled vinegar and hot water; and a throat salve made from a preparation of dried beetles. Finally, he was subjected to an enema and was bled five times, resulting in a loss of forty percent of his blood volume. It should be understood that this was the optimal treatment of such disorders in 1799. Some twenty-first century treatments such as hydroxychloroquine and a horse de-wormer to treat Covid-19 may be subject to similar disparagement.

By 1881 four presidents had died in office, including two by assassination. In addition, Andrew Jackson had been shot in an 1806 duel and carried a bullet close to his heart until his death. (He shot his duelist to death after receiving the bullet.) The second of the two assassinated presidents was James Garfield, who on July 2, 1881 was shot with two bullets by an office seeker, Charles Guiteau, as Garfield was about to make a railroad trip from Washington DC for a vacation. One bullet caused a superficial arm wound; the other entered the right thorax, fractured a lower rib and lodged several inches below the pancreas to the left of the spine. Unlike Washington, Garfield was forty-nine years old, robust, and energetic, although he was supposed to have had a “weak stomach” for years. After multiple medical interventions, Garfield lingered for two and a half months, dying on September 19th.

In that same year of 1881, the non-invasive sphygmomanometer was invented for the measurement of blood pressure. The first description of what would be called Tay-Sachs disease was published. A neonatal incubator for routine care of premature infants was introduced by a Parisian physician, a Cuban physician proposed that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitos rather than a miasma, and Pasteur discovered a vaccine for anthrax. The germ theory of disease was on the horizon but was still unknown to most clinicians. And twelve days after Garfield was shot, Dr. George Goodfellow performed the first laparotomy and removed a bullet from a miner who had been shot in Tombstone, Arizona.

Why did a relatively young, vigorous man die within months after being shot? Andrew Jackson survived for years with a bullet close to his heart. Garfield’s residual bullet was located in an area that did not affect organ function, although it was in close contact with the splenic artery.

Several factors could have led to his death. (1) His physicians attempted to find the bullet for several weeks, probing under unsanitary conditions: neither instruments nor hands were sterilized. (2) The White House itself had an unsanitary plumbing system and the basement was saturated with excrement. (3) Although Joseph Lister had demonstrated sanitizing instruments in operating rooms in Europe by this time, Garfield’s physician, Dr. Willard Bliss, had rejected Lister’s methods, quarreled with other physicians in consultations, did not heed their advice, and continued to infect Garfield with his probing. Bliss had been called in by Robert Todd Lincoln, a friend, because Bliss had attended the wounded President Lincoln. But in that situation, Lincoln died shortly after being shot, so Bliss did not have the opportunity to produce an unsanitary condition.

In addition to Bliss’s constant probing for the elusive bullet, he treated Garfield with high doses of quinine and morphine, along with sips of brandy. In his quest for the bullet, Bliss even used the resources of Alexander Graham Bell, who provided a machine using sound waves that was unsuccessful in finding the bullet. However, Bell explored the right side of the abdomen, while the bullet was lodged in the left retroperitoneum.

Although in the first few days after his injury Garfield experienced vomiting, extreme pain, and shock, he appeared to recover after several days. Over the summer, he suffered from fever, chills, and confusion. His weight dropped from 210 pounds to 130 and he was in severe pain from the constant probing and surgical incisions to recover the bullet.

Aside from Dr. Bliss, several prominent physicians were called in for consultation, including Dr. Hayes Agnew, a surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania, and Dr. Frank Hamilton from Bellevue Hospital in New York. Both probed the president with their fingers. After the wound began to discharge pus and bone, Dr. Agnew made an incision at the end of the fourth week to enlarge the opening in his flank.

The immediate cause of Garfield’s death was hemorrhage from a mesenteric artery and a large abscess near the gallbladder with a long, suppurating channel that extended from the external wound almost to the groin. Other causes of death that were considered include the rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm and ischemic heart disease. The latter was considered because Garfield complained of severe chest pain just before he died.

In retrospect, it would have been difficult in a patient of Garfield’s robust build to extract the bullet, which was lodged behind the pancreas and surrounded by spiculae of bone. Surgery would have involved dissection of vessels and nerves superimposed on the bullet, with the danger at least of hemorrhage.

Ironically, Dr. Bliss himself died of sepsis after cutting his hand while dressing one of Garfield’s wounds. Charles Guiteau, the assassin, claimed that “the doctors killed Garfield, I only shot him.”

References

- White R. The republic for which it stands. Oxford University Press 2017.

- Fish, S. The death of President Garfield. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 1950; 24:378-392.

- Ehrhardt Jr., John D. and J. Patrick O’Leary. “Yes, I shot the President, but his physicians killed him: The assassination of President James A. Garfield.” Poster, American College of Surgeons, 2017.

- Pappas TN, Joharifard S. Did James A. Garfield die of cholecystitis? Revisiting the autopsy of the 20th president of the United States. The American Journal of Surgery. 2013;206(4):613-618.

PHILIP R. LIEBSON, MD, received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he served on the faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College since 1972 and held the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Summer 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply