Ad A. Kaptein

Barend W. Florijn

Pim B. van der Meer

Leiden, the Netherlands

|

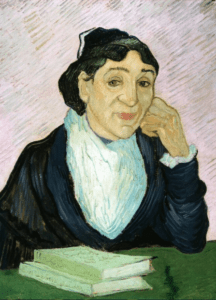

| L’Arlésienne (portret van Madame Ginoux). Vincent Van Gogh. 1890. Kröller-Müller Museum. |

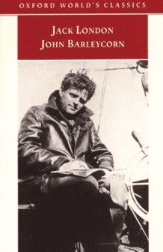

A thousand words every morning—with iron discipline, Jack London adhered to his writing routine. Later in the day, he would turn to John Barleycorn: beer, wine, whisky, and brandy. His John Barleycorn: Alcoholic Memoirs (1913) tells of his drinking career, which took off after inadvertently sipping his first beer at age five. The book does not fit other narratives of calamities, finding comfort in drink, failures to get out of the grip of alcohol, admissions to hospitals and clinics, thefts, sexual excursions, partners’ desperation, incursions with the law, medical misery, and early demise, with the protagonist blaming everyone except himself. John Barleycorn provides an atypical alcohol narrative in a health humanities context.1

Alcohol is a theme with great prevalence and relevance in human life and illness. Books that address this topic include Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry, in which the reader follows the protagonist page-by-page into the abyss. The Drinker by Hans Fallada is an autobiographical narrative of the derailment of a successful businessman, starting with a financial disaster and ending in a psychiatric institution. The Lost Weekend by Charles Jackson, the story of a five-day binge (“. . . never put off till tomorrow what you can drink today” (p. 93)), follows the protagonist on a walk of some eighty blocks in Manhattan in the sweltering heat carrying a typewriter to be pawned for booze money, and leaves the reader exhausted, sad, and wondering whether one can fully understand addiction.

Films that portray alcohol addiction include Le Cercle Rouge, a shocking representation of an episode of delirium tremens. In The Verdict, Frank Galvin, a lawyer, has poisoned his professional and personal life with alcohol and is now seeking redemption by bringing a medical malpractice case against a Catholic hospital. Leaving Las Vegas exposes the viewer to an attempted suicide with alcohol as the chosen method. An exhaustive list of movies on alcohol is provided in two brilliant books.2-3

Alcohol is also a common theme in music genres such as pop, rock, and jazz. Many musicians use spirits as an inspiration when composing, listeners enjoy it to enhance their experience, and musicians and listeners alike may combine music and alcohol as a means to escape stress. Some musicians are notorious for drinking huge quantities of alcohol, making it a major cause of death.4

Alcohol and art have a close albeit dark relationship as well: alcohol is associated quite closely with the lives of many painters (e.g., Bacon, Gauguin, Van Gogh).5 Van Gogh’s6 L’ Arlésienne depicts the proprietor of a café where absinthe was served by her to the customers, Vincent being one of them. The green hue in the painting may reflect “the green fairy.”7

|

| Cover of John Barleycorn: Alcoholic Memoirs. Source |

Literature, film, music, and art that represent persons with drinking issues often implicitly or explicitly conceptualize alcohol and “alcoholics” in moral terms: as a fault of the individual, a failure of moral fiber in resisting temptation. Gradually, addiction has become medicalized, psychiatrized, and pathologized: “Your alcohol addiction is not your fault, it is a disease.”8 This conceptualization also has major implications for the diagnosis, treatment, and societal attitudes towards addicted “patients” and the representation of alcohol addiction in media and society. Conceptualizing addiction as a medical problem based solely on biological and neurological phenomena reflects reductionistic thinking, and leads to medicalization and pathologizing of human behavior, preventing adequate intervention strategies.8

There are alternative conceptualizations of addiction. A recent paper in NEJM contrasts the “brain disease model and stigma” with the “learning model and empowerment” of addiction.9 “Alternatives to the brain disease model often highlight the social and environmental factors that contribute to addiction, as well as the learning processes that translate these factors into negative outcomes.” Problematic in the brain disease model is that “. . . the disease definition can reinforce the belief that a ‘badness’ is built in . . . resulting in feelings of inferiority and shame . . . and can curtail attempts to improve one’s functioning without medical care.”

This fits with health psychology models for the response to and management of chronic illness, including problems with addictive substances.10 The Common Sense Model conceptualizes how physical, psychological, and social stimuli that differ from what is perceived to be normal elicit illness perceptions. These illness perceptions, in turn, elicit coping responses such as drinking or abstaining from alcohol. The combined effects of illness perceptions and coping behavior, in combination with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, determine outcomes. Managing illness perceptions, teaching coping strategies, and replacing maladaptive behaviors with adaptive self-management techniques help people with a chronic condition such as problematic drinking improve their quality of life. One dimension of illness perception, causal attribution, asks respondents to “list in rank order the three most important factors that you believe caused your illness.” Biomedicine would respond that an illness such as addiction is caused solely by factors in the brain and in the genes. Biopsychosocial medicine would include the patient’s narrative, circumstances, and the perspectives reflected in various art genres.11

John Barleycorn is subtitled “Alcoholic Memoirs.” In the book, Jack London analyzes his drinking behavior over the years. A crucial finding of these analyses pertains to the causal attributions the author makes about his drinking behavior, which do not include neural mechanisms or genetic make-up, but social circumstances. Some quotes:

“What could I do, here in this company of big men, all drinking whisky?” (p. 41)

“Wherever life ran free and great, there men drank.” (p. 43)

“Drinking was the way of the life I led, the way of the men with whom I lived.” (p. 58)

“I drank because the men I was with drank, and because my nature was such that I could not permit myself to be less of a man than other men at their favorite pastime.” (p. 97)

The author summarizes the self-perceived causes (causal attributions) of his behavior regarding alcohol: “Not one drinker in a million began drinking alone. All drinkers begin socially, and this drinking is accompanied by a thousand social connotations such as I have described out of my own experience in the first part of this narrative . . . The part that alcohol itself plays is inconsiderable, when compared with the part played by the social atmosphere in which it is drunk” (pp. 205–6).

A theoretically based analysis of an autobiographical novel on drinking alcohol may help in examining existing models of addiction. John Barleycorn conceptualizes and supports what Lewis labels a model of learning and empowerment. Prohibition did not produce the intended effect; medicalization and pathologizing of alcohol addiction appear to share this fate.

In the Common Sense Model, the patient is no longer seen as a “poor historian”12 or a “lay epidemiologist.”13 These labels reflect an outdated biomedical model and deny patients’ perceptions and narratives of their own illness and its management. It is the patient who is the expert in living with a chronic condition.14-16 Examining self-perceived causes of an illness contributes to a better quality of interaction between patients and healthcare professionals, higher patient satisfaction with the healthcare system, and better behavioral, medical, and social outcomes. This reflects what Virchow stated long ago, that “Medicine is a social science in its bone and marrow.”17

References

- Greene JA, Loscalzo J. “Putting the patient back together – Social medicine, network medicine, and the limits of reductionism.” N. Engl. J. Med. 2017; 377: 2493 – 2499.

- Wijdicks EFM. Cinema MD, A history of medicine on screen. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Denzin NK. Hollywood shot by shot. Alcoholism in American cinema. New York, De Gruyter, 1991.

- Oksanen A. “To hell and back: Excessive drug use, addiction, and the process of recovery in mainstream rock autobiographies”. Subst. Use Misuse. 2012; 47: 143 – 154.

- Bodin G, d’Ambrosio LP. Medicine in art. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2010.

- Voskuil P. “Vincent van Gogh and his illness: A reflection on a posthumous diagnostic exercise.” Epilepsy Behav. 2020; 111: 107258.

- Robles NR. “Absinthe: the green fairy”. Hektoen Int. 2020; 13: (3).

- West R, Brown J. Theory of addiction, 2nd ed. Wiley, Chichester, 2013.

- Lewis M. “Brain change in addiction as learning, not disease”. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018; 379: 1551 – 1560.

- Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. “The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management.” J. Behav. Med. 2016; 39: 935 – 946.

- Florijn BW, van der Graaf H, Schoones JW, Kaptein, A.A. “Narrative Medicine: A comparison of terminal cancer patients’ stories from a Dutch hospice with those of Anatole Broyard and Christopher Hitchens.” Death Studies. 2019; 43: 570-581.

- Tiemstra J. “The poor historian”. Acad. Med. 2009; 84: 723.

- Nuti SV, Armstrong K. “Lay epidemiology and vaccine acceptance”. JAMA. 2021; 326: 301- 302.

- Kaptein AA, Hughes BM, Murray M, Smyth JM. “Start making sense: art informing health psychology”. Health Psychol. Open. 2018; 5: 1-13.

- Kaptein AA. “Novels as data: Health humanities and health psychology.” J. Health Psychol. 2021, in press.

- Kaptein AA, van der Meer PB, Florijn BW, Hilt AD, Murray M, Schalij MJ. “Heart in art: cardiovascular diseases in novels, films, and paintings”. Phil. Eth. Human. Med. 2020; 15: 2.

- Rather LJ. “Rudolph Virchow and scientific medicine”. Arch. Intern. Med. 1957; 100: 1007 – 1014.

AD A. KAPTEIN, PhD, publishes on Health Humanities and Literature & Medicine, examining the patient’s view on illness.

BAREND W. FLORIJN, MD, PhD, is a neurologist who publishes on narrative medicine in relation to neurology.

PIM B. VAN DER MEER, MD, is a physician in training who publishes in the area of neurology and psychiatry.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply