Kathryne Dycus

Madrid, Spain

|

| Peter Panum. Scan from P. Hansens “Illustreret Dansk Litteraturhistorie”, anden meget forøgede udgave, 2. bind, 1902. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia. |

In 1846, the Faroe Islands experienced an outbreak of measles, the likes of which had not been seen in sixty-five years. The Danish government called upon a newly graduated physician, Peter Ludwig Panum, to investigate and control its spread.

Panum wrote of the experience in his seminal text, “Observations Made During the Epidemic of Measles on the Faroe Islands in 1846,” which continues to be taught in public health and medical programs across the globe. Panum’s study was of great significance because it was among the first extensive contributions to the modern field of epidemiology—a discipline that studies factors that affect the health of populations.

When there are disease outbreaks, epidemiologists are called upon for their expertise. They investigate the causes of disease, determine strategies to curb its spread, and aim to prevent further outbreaks from occurring within a population. Among the most famous epidemiologists of the 1800s were Panum (who studied the spread of measles), and the English physicians John Snow and William Budd, who studied the spread of cholera and typhoid fever, respectively.

Shifting from miasma theory to contagion theory

Peter Panum, who was born in 1820 on the Danish island of Bornholm, started out as a science teacher. He later passed his medical examinations in 1845 at the University of Copenhagen. The next year, the Danish government—which had always been concerned about the public health of the Danish people for both economic and military reasons—sent the newly minted physician on a special mission to the Faroe Islands. “In 1846, there were 7,864 individuals living on the Faroe Islands. Of these, 6,100 contracted measles, and 170 died, a case fatality rate of 2.8 percent. Of the 6,100 measles victims, Panum treated approximately 1,000.”1

During his five-month stay, Panum diligently studied the cause and transmission of disease, exploring innovative solutions tailored to the islands’ unique culture and inhabitants.

His investigation and resulting study helped shift the focus of epidemiology from miasma theory to contagion theory. Miasma theory, a common folk theory of disease, was codified by Lancisi in 1717 in De Noxiis Paludum Effiuviis. In the nineteenth century, it was the prevailing theory of why disease and death occurred in humans and the key component of explaining the origin of epidemics. It was based on the notion that when air was of bad quality, the person breathing the air would become susceptible to illness. Panum, however, resisted this theory, as it failed to explain the measles epidemic he was witnessing. The disease decimating the population of the Faroe Islands seemed better aligned with contagion theory, which held that disease could be spread by touch, whether of infected cloth or food or people. He wrote:

|

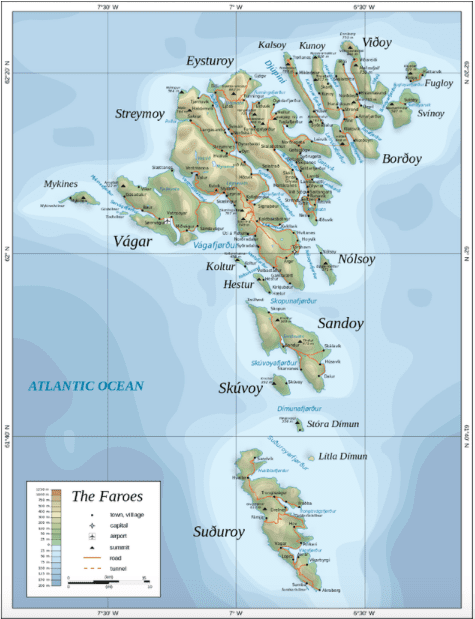

| Topographic map of the Faroe Islands. Created by Oona Räisänen, January 28, 2009. CC BY-SA 3.0. Via Wikimedia |

If, among 6,000 cases, of which I myself observed and treated about 1,000, not one was found in which it would be justifiable, on any grounds whatever, to suppose a miasmatic origin of measles, because it was absolutely clear that the disease was transmitted from man to man and from village to village by contagion, whether the latter was received by immediate contact with a patient or was conveyed to the infected person by clothes, or the like, it is certainly reasonable at least to entertain a considerable degree of doubt as to the miasmatic nature of the disease.2

Panum’s theories of contagion were later confirmed by the Englishman John Snow during a London cholera outbreak in 1848. Snow’s investigation of the epidemic led him to conclude that the Broad Street pump was the direct source of the waterborne disease; once removed, the epidemic came to a swift end.

Geography of the Faroe Islands and of Disease

Sculpted by Ice Age glaciers, the islands, with their dramatic cliffs, lie halfway between Scotland and Iceland. The key to Panum’s investigation was the isolated nature of the Faroe village settlements dotting the archipelago. Since coastal valleys, or fjords, separate the various populations of the islands, the history and transmission of disease in each small settlement could be studied independently of the others. Each village was its own mini-epidemic. “The isolated situation of the villages,” Panum wrote, “and their limited intercourse with each other, made it possible in many, in fact in most cases, to ascertain where and when the person who first fell ill had been exposed to the infection.”3

Panum studied fifty-two different villages. First, he identified the index, or first case in each village. Then he observed the time between the first case in each village and the next or subsequent cases there, ultimately determining that the incubation period for measles was about two weeks. He wrote:

In Fuglefjord, on Østerø, on account of my observations, I acquired the reputation of being able to prophesy. On my first arrival there, the daughter of Farmer J. Hansen, churchwarden, had recently had measles, but had then got up, and, except for a slight cough, was almost entirely well. All the other nine persons in the house were feeling well in every respect and expressed the hope that they would escape the disease. I inquired as to what day the exanthema [rash] had appeared on the daughter, asked for the almanac, and pointed to the fourteenth day after that . . . with the remark that they should make a black line under that date, for I feared that on it measles would show itself on others in the house . . . As it turned out I was summoned to Fuglefjord again ten days later and was met with the outcry: “What he said was correct! On the day he pointed out the measles broke out, with its red spots, on all nine.”4

|

|

Faroe Islands – Vestursíðan av Suðuroy. By Ehrenberg Kommunikation, October 19, 2010. CC BY-SA 2.0. Via Wikimedia. |

Panum also supplied evidence of long-lasting immunity by interviewing older individuals who had been infected many years earlier, none of whom contracted measles in 1846. He wrote, “If recovery from measles sixty-five years before could insure people against taking the disease a second time, it might be supposed that still greater protection would be afforded by having recovered from it a shorter time before.”5

Panum observed that the part of the population who had survived the measles outbreak of 1781 learned that “the spread of measles could be hindered by isolating places or even houses; and the aged people, who had preserved the recollection of this from their youth, effected in many places, on their own responsibility, a sort of quarantine . . . whereby the places concerned were entirely or partially spared.”6 The overall consequence in maintaining quarantine was that “about 1,500 of the inhabitants of the Faroe Islands were saved from measles.”7

Perhaps another reason people on the Faroe Islands were willing to undertake a voluntary quarantine was that they cared deeply about other people. Panum wrote, “the isolated social life and the common dangers occasioned by natural conditions certainly tend to strengthen greatly the feeling that all men are brothers, and it is to the praise of the Faroe folk that they show forth this feeling by their actions.”8 One such action was self-isolation, not only to protect the self but others.

Panum’s legacy

Panum’s “medical ethnography of the Faroe Islands and his clinical insights were characteristic of what at the time was known as the ‘geography of disease,’ or ‘geographic pathology,’ early names for epidemiology.”9 This fundamental beginning cleared the way for the work of Pasteur, Lister, and others who introduced modern germ theory in the late 1800s, the idea that a particular disease can be traced to a specific microbe. This resulted in the Golden Age of Microbiology in which many types of bacteria were isolated and shown to cause various human diseases.

The Panum Institute in the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen is named after Peter Ludwig Panum, an innovator in the history of public health. Panum’s “Observations Made During the Epidemic of Measles on the Faroe Islands in 1846” is a study that relies on logic, close observation and analysis, and the interpretation of numerical data.

“The episode would be hard to parallel in the history of medicine. Here was a boy just out of medical school who wrote one of the classics of our science.”10 Although Panum later served as a navy physician during the first Dano-Prussian war, and went on to conduct experimental research at medical universities in Kiel and Copenhagen, he is perhaps best remembered as a public health innovator who blended sharp ethnographic accounts with epidemiologic and medical insight.

End Notes

- Golbeck, C. Melgaard. “Peter Ludwig Panum and the Danish School of Epidemiology,” The Bridge 37.2 (2014): 19-24.

- Peter Ludwig Panum. “Observations made during the epidemic of measles on the Faroe Islands in the year 1846.” New York: Delta Omega Society; distributed by the American Public Health Association, 1940.

- Panum, “Observations.”

- Panum, “Observations.”

- Panum, “Observations.”

- Panum, “Observations.”

- Panum, “Observations.”

- Panum, “Observations.”

- A. Golbeck, C. Melgaard, “Peter Ludwig Panum and the Danish School of Epidemiology.”

- “The Centenary of Panum.” American Journal of Public Health 36.7 (1946): 795-797.

References

- Melgaard, Craig A. and Golbeck, Amanda L. “Peter Ludwig Panum and the Danish School of Epidemiology.” The Bridge 37.2 (2014): 19-24.

- Panum, Peter Ludwig. Observations made during the epidemic of measles on the Faroe Islands in the year 1846. New York: Delta Omega Society; distributed by the American Public Health Association, 1940.

- “The Centenary of Panum.” American Journal of Public Health 36.7 (1946): 795-797.

KATHRYNE DYCUS is a writer and educator based in Madrid. She studied British Romanticism at the University of Glasgow and writes for the anthropology journal Mammoth Trumpet.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply