Fangzhou Luo

Portland, Oregon, United States

Philammon declaring his love for Hypatia. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

After a few failed attempts to redirect a flirtatious student to “higher pleasures” like music, the Ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician Hypatia resorted to revealing where she was in her menstrual cycle to deter him. The philosopher who recorded this—Damascius—does not specify if this student was Orestes,1 who remained a loyal admirer of Hypatia’s his entire life. What is clear is that the student was “ashamed” and “shocked”1 following the incident.

Hypatia’s professionalism in handling her student echoes Plato’s “Ladder of Love”—that to be a philosopher is to always pursue wisdom, and that possessing the love of wisdom should yield a pregnancy not involving carnal attractions.2 And while Hypatia’s demonstrative method would not be appropriate in today’s classroom settings, what remains true is that being “shocked” and “ashamed” is still the reaction many people have at the mention of menstruation. This demonization of menstruation still haunts many cultures and societies.

The study of female reproductive science has been disappointing for thousands of years. Many ancient definitions of menstruation uncover men’s fear of this phenomenon and inability to control it. The combination of that which is unknown and unconquerable in a woman undeniably renders her very unlikeable (Look what happened to Hypatia—she was murdered).

After the emergence of more advanced scientific methodology, some hearsay-based findings now appear exceptionally backwards, even through the lens of history. For example, a review article by Maybin and Critchley begins with a paragraph quoting Aristotle and Pliny the Elder on menstruation.3 In Pliny’s encyclopedia, menstruation was thought to cause disastrous agricultural outcomes such that a menstruating woman “sterilizes the seeds she touches, decays the shoots, dries up gardens, and fruit falls upon where she sits under the tree.”4 Pliny’s admonitory definition was echoed and expanded on by Isidore of Seville centuries later. He postulated that menstruation could also corrupt iron, blacken copper, madden a dog, and that: “The glue of pitch, which is dissolved neither by iron nor water, when polluted with this blood spontaneously disperses.”5, 6

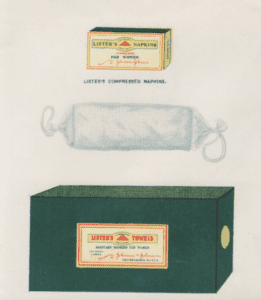

First mass-produced feminine napkins by Johnson & Johnson in 1897. Image courtesy: Johnson & Johnson Archives.

It is not surprising that Aristotle regarded women as weak and inferior. But for as dry and dense as Aristotle’s copious lecture notes are, that he found time to criticize female physiology might actually have been a gesture of flattery. Unlike Pliny the Elder, Aristotle put great effort into the interpretation of female physiology in On The Generation of Animals, History of Animals, and Politics. He stated that women are “necessarily incomplete,” and that menstruation indicates the lack of activation from semen, resulting in wasted nourishment that otherwise should have benefitted an embryo.7, 8

With this background, progress in female reproductive health research has been slow. Two millennia after Aristotle, “hysteria” sprang to stardom in the eighteenth century and menstruation was no longer the dominant female disease.9 By the end of the nineteenth century, feminine products were designed to improve quality of life and were advertised in public. It was not until the 1940s that menstrual bleeding was shown to be accompanied by a change in endometrial thickness.10 Estrogen and progesterone receptors were not discovered until the second half of the twentieth century.11, 12 We now have a scientific understanding of menstruation: its onset proceeds from progesterone withdrawal,13 during which the recruitment of leukocytes, extracellular matrix breakdown, and cell death create an inflammation-like process.14 Once demystified, menstruation no longer represented “incompleteness” and “inferiority.” Progress was being made on the whole picture of female reproductive health.

Or perhaps not. Even today, it seems that childless women are invisible, and the non-pregnant years of a woman’s life fail to excite decision-makers. A literature search of terms such as pregnancy, placenta, and embryo yields more than one million results, while conditions such as vaginosis, chlamydia, endometriosis, and polycystic ovarian syndrome are not as well studied. Many studies of the microbiome and inflammation are only dedicated to the impact on fertility. Research funds are similarly allocated—where money goes, results follow.

Most mainstream scientific societies that study female reproductive health were originally founded to tackle fertility and sterility problems. More than half a century later, that vision has not changed much. We may have advanced beyond the demonization of menstruation, but old ideas still remain, and there is still work to be done in supporting all aspects of women’s reproductive health.

Reference

- Watts EJ. Hypatia: THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF AN ANCIENT PHILOSOPHER. Women in Antiquity. Oxford University Press; 2017.

- Plato, Reeve CDC. Plato on love : Lysis, Symposium, Phaedrus, Alcibiades, with selections from Republic, Laws. Hackett Pub. Co.; 2006:xli, 226 p.

- Maybin JA, Critchley HO. Menstrual physiology: implications for endometrial pathology and beyond. Hum Reprod Update. Nov-Dec 2015;21(6):748-61. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv038

- Pliny. Book VII. Historia Naturalis. B. G. Teubner; AD 77:chap 13.

- Seville Io. The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. stephen a. barney wjls, j . a. beach, oliver berghof Cambridge University Press; 615-630.

- Finn CA. Why do women menstruate? Historical and evolutionary review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Dec 1996;70(1):3-8. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(96)02565-1

- James SL, Dillon S. A companion to women in the ancient world. Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:xxiv, 616 p.

- Aristotle. History of Animals. Creswell R. GEORGE BELL & SONS; 1887.

- Tasca C, Rapetti M, Carta MG, Fadda B. Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:110-9. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110

- Christiaens GC. J.E. Markee: menstruation in intraocular endometrial transplants in the rhesus monkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Oct 1982;14(1):63-5. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(82)90086-7

- Hapangama DK, Kamal AM, Bulmer JN. Estrogen receptor beta: the guardian of the endometrium. Hum Reprod Update. Mar-Apr 2015;21(2):174-93. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu053

- Dwyer AR, Truong TH, Ostrander JH, Lange CA. 90 YEARS OF PROGESTERONE: Steroid receptors as MAPK signaling sensors in breast cancer: let the fates decide. J Mol Endocrinol. Jul 2020;65(1):T35-T48. doi:10.1530/JME-19-0274

- Maybin JA, Murray AA, Saunders PTK, Hirani N, Carmeliet P, Critchley HOD. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha are required for normal endometrial repair during menstruation. Nat Commun. Jan 23 2018;9(1):295. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02375-6

- Emera D, Romero R, Wagner G. The evolution of menstruation: a new model for genetic assimilation: explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness. Bioessays. Jan 2012;34(1):26-35. doi:10.1002/bies.201100099

FANGZHOU LUO works as a research technician in the field of female reproductive biology and has been inspired to write about women’s health. Although Luo possesses a degree in biology and a minor in chemistry, Luo once wanted to pursue a degree in philosophy, an idea which eventually gave in to the need of surviving the living cost in Portland, Oregon.

Leave a Reply