Kevin R. Loughlin

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

|

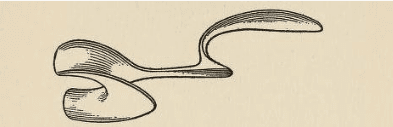

| Figure 1. The cheek retractor used in Cleveland’s operation. From The surgical operations on President Cleveland in 1893 by W. W. Keen. 1917. Via the Internet Archive. |

William Williams Keen served in the American Civil War and was present at the first and second Battle of Bull Run and Antietam.1 His battlefield experience led him to publish in 1864 “Gunshot Wounds and other Injuries of the Nerves and Reflex Paralysis.” He would become one of the preeminent surgeons of his era and was recognized with many professional awards, including becoming chief of surgery at Jefferson Medical College and serving as president of the American Surgical Association, the American Medical Association, the American Philosophical Society, and the International College of Surgeons.

He would go on to be elected an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Edinburgh, and Ireland and was awarded the Bigelow Medal by the Boston Surgical Society.1,2 He was the first surgeon to perform ventricular punctures, the first American surgeon to successfully remove a primary brain tumor, and he counted Harvey Cushing among his proteges.1-3 All these honors and accomplishments notwithstanding, it is perhaps the fact that four U.S. presidents relied on his expertise for the care of themselves or their family members that truly distinguishes Keen’s place in the panorama of American surgery.

Keen was one of the physicians involved in the clandestine surgical procedures performed on President Grover Cleveland in July of 1893. These procedures were performed surreptitiously aboard the yacht Oneida while it sailed up the East River in New York City to Buzzard’s Bay off Cape Cod.

In order to understand the context of President Cleveland’s health and its political and economic implications, it is necessary to provide a brief review of the Silver Crisis and the Panic of 1893. The genesis of the Panic of 1893 began in the 1870s and 1880s as many Americans began to have a demand for cheaper money. This began with a five-year depression following the Panic of 1873, which caused cheap money advocates to join the silver-producing interests to urge a return to bimetallism, the use of both silver and gold as a standard. This prompted the U.S. Treasury to purchase between two and four million dollars of silver from western miners to be minted into silver dollars,4 beginning a period of increasing inflation and undermining the gold standard as the backing of U.S. currency.

In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which allowed for even greater government purchase of silver to 4.5 million ounces per month, threatening the U.S. Treasury gold reserves and resulting in a $156 million increase in the amount of paper money in circulation.5

At the top of President’s Cleveland’s agenda was to convince Congress to repeal the Sherman Act. What made the political stakes of Cleveland’s health even higher was that to “balance” the ticket, his vice president was Adlai Ewing Stevenson, who was a pro-silver man and opposed repeal of the Sherman Act.

Soon after his inauguration on March 4, 1893, President Cleveland began the requisite political maneuvers to ensure repeal of the Sherman Act. A presidential speech to Congress was tentatively scheduled for August. However, on June 18, 1893, Doctor R.M. O’Reilly, Cleveland’s personal physician, examined a rough place on the roof of Mr. Cleveland’s mouth. It appeared to be an ulcer about the size of a quarter that extended from the molar teeth and encroached slightly on the soft palate. A small biopsy was performed, which returned as suspicious for malignancy. Cleveland was a cigar smoker, although the association between that behavior and oral cancers was not appreciated at the time. Mr. Cleveland consulted Doctor Joseph D. Bryant, his longtime friend and confidant, who advised removal of the lesion as soon as possible.

He quickly made his decision. Congress would recess on June 30, and he would have the surgery on July 1. He was scheduled to address Congress on the Silver Crisis on August 7. In addition to Doctor Bryant, the surgical team included Doctors W.W. Keen, John F. Erdman, Edward Janeway, and a young dentist, Ferdinand Hasbrouck, who was experienced in the administration of a new anesthetic, nitrous oxide. The president traveled to New York City and met his surgical team on Commodore E.C. Benedict’s yacht, the Oneida, which was anchored in the East River behind Bellevue Hospital. The plan was to perform the entire operation within the oral cavity utilizing a special cheek retractor, which Keen had discovered during one of his medical meetings in France. (Figure 1) It was agreed by all parties that the surgery and postoperative care would be totally done in secret, and with the aid of the cheek retractor there would be no external incisions.

The anesthetic was a concern for the team. The president was corpulent with a thick neck. It was decided that Doctor Hasbrouck would begin the operation using nitrous oxide and, if necessary, change to ether. Doctor Hasbrouck first extracted the two left upper bicuspid teeth under nitrous oxide and Doctor Bryant made the necessary incisions on the roof of the mouth.

As the operation proceeded, Doctor Hasbrouck converted the anesthetic to ether. The entire left upper jaw was removed, from the first bicuspid tooth to just beyond the last molar. The tumor extended almost to the midline, but fortunately did not involve the floor of the orbit. A small portion of the soft palate was also removed.6

The total blood loss was less than six ounces and at the conclusion of the two-hour operation, the patient’s pulse was eighty and the surgical cavity was packed with gauze. The only narcotic necessary was an injection of one-sixth of a grain of morphine.6

The Oneida’s route continued up the East River to Long Island Sound and on July 5, the yacht reached the President’s residence, Gray Gables at Bourne, Massachusetts on Cape Cod. The pathology was reviewed by William Welch of Johns Hopkins, the most prominent pathologist of the era. He found what appeared to be a positive margin on the pathology specimen.

On July 17, the Oneida returned to Bourne and the President boarded the yacht. The original surgical team performed the second operation. The pathological review of the second specimen confirmed negative margins.

However, the gaping hole in the President’s mouth rendered his speech unintelligible. Doctor Kassan C. Gibson, a New York orthodontist, fashioned an artificial vulcanite prosthesis for his jaw, which restored his normal speech.7 On August 5, President Cleveland left Gray Gables and returned to Washington, D.C. He gave his speech on August 8 to a special session of Congress as scheduled, and his speech was instrumental in the ultimate repeal of the legislation.8

|

| Figure 2. A picture of FDR on crutches. Photographers rarely photographed him using crutches. Photo from 1924. Via the National Archives. |

The public story given was that the President simply had two infected molars removed and was suffering from rheumatism. The President and his team thought that their ruse had been successful. However, on August 29, 1893, journalist E.J. Edwards published an account in the Philadelphia Press that Cleveland had undergone a much more serious operation than previously acknowledged.7 Edwards’ facts were attacked and he was assailed as a liar by some.6 Upon leaving office, Cleveland returned to Princeton, New Jersey and served as a lecturer and trustee of the university. He died of a heart attack without apparent evidence of a recurrent tumor at Princeton in 1908.

W.W. Keen continued to be clinically active, lectured widely, and his reputation continued to grow. His next involvement with the White House involved William Howard Taft in 1909.

The circumstances centered around a request by President Taft for consultation by Doctor Keen for his sister-in-law, who had been diagnosed with a brain tumor that year. Taft had written, apparently to a relative, “I believe the greatest authority on the subject is W.W. Keen of Philadelphia, whom I know very well.”9 The outcome of the consultation and any treatment remains unknown.

Keen had a relationship with Woodrow Wilson and several members of Wilson’s family before he entered the White House. Wilson had cardiovascular disease and his first health issue became apparent in 1896 when he was on the Princeton faculty. Although only thirty-nine years old at the time, Wilson manifested a weakness and loss of dexterity of his right hand, a numbness in the tips of several of his fingers, and some pain in the right arm.10 He traveled to Philadelphia to consult with Keen. It is not known what diagnosis Keen made, but the underlying diagnosis was an occlusion of a central branch of the left middle cerebral artery.10 However, Keen apparently did not feel it was serious enough to advise Wilson to postpone an upcoming trip to Great Britain.

Wilson continued his academic career and became president of Princeton in 1902. In the summer of 1904, he developed transient weakness in his right hand, which resolved without apparent sequelae. He exhibited no other health issues until May 28, 1906, when he developed loss of vision in his left eye and weakness in his right arm. He traveled to Philadelphia to consult George de Schwenitz, a noted ophthalmologist, and Keen.11

Wilson recovered from this event, though not completely. He traveled to Europe and while in Edinburgh, he consulted an ophthalmologist, George A. Berry, who found that Wilson had improved to the point that he could read.12 He regained most of the function of the right hand but used a pen holder to write and had a rubber stamp made for his signature.13

Keen and Wilson continued their relationship, both professional and personal. Keen operated on Mrs. Ellen Wilson in the spring of 1912 and a few years earlier had operated on two of Wilson’s daughters at Jefferson Hospital.14

Wilson’s hopes for the League of Nations are well known. In the autumn of 1919, Wilson embarked on a countrywide speaking tour to garner support for his initiative. He returned to Washington on September 29 and three days later, on October 2, Wilson awoke without feeling in his left hand and his second wife, Edith Bolling Wilson, noted that the hand was paralyzed. His personal physician and friend, Rear Admiral Cary T. Grayson, was notified and he consulted Francis X. Dercum, a noted Philadelphia neurologist. He diagnosed another stroke, and in her memoir Edith Bolling Wilson singles out Dercum for his kindness, reassurance, and advice.15 Although Mrs. Wilson does not specifically mention Doctor Keen coming to the White House to examine President Wilson at this time, it is not unreasonable to speculate that Keen had some input into the management of the President’s condition. First, as mentioned previously, he already had a longstanding personal and professional relationship with Wilson and members of his family. Beyond that, Doctors Dercum and Keen were both on the faculty of Jefferson Medical College. It seems very likely that Doctor Dercum would have sought Doctor Keen’s advice on the management of his very important patient. Wilson recovered from these events, including a bout of transient urinary retention,15-17 and completed his term of office. Wilson ultimately died on February 3, 1924 of a cerebrovascular accident.

On August 10, 1921, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a vigorous thirty-nine-year-old man from one of America’s oldest families, who had recently lost a bid for the vice-presidential nomination of the Democratic party and was considering whether he should run for governor of New York. He was starting a summer vacation on Campobello Island in New Brunswick, Canada on the Bay of Fundy. He had spent the day sailing and swimming in the very cold water of the bay. That evening he experienced a chill associated with some anorexia and fever. He soon developed paralysis of the lower extremities that progressed to his trunk and part of his hand.

A local physician, Edward Bennett, was unsure of the diagnosis and told Roosevelt to get a second opinion. Phone calls were made and the eighty-four-year-old W.W. Keen was found vacationing in Bar Harbor, Maine.18 He agreed to drive to Campobello Island and see Roosevelt. He arrived on August 14 and made the diagnosis of a thrombosis of the vertebral artery causing reversible paralysis. However, Roosevelt’s condition worsened over the next few days and Keen changed his diagnosis to a lesion in the spinal cord. There was no improvement in Roosevelt’s condition and family members began to seek additional consultations.

They contacted Robert A. Lovett, a professor of orthopedic surgery at Harvard and a leader in the field of poliomyelitis. He arrived at Campobello on August 25 and examined Roosevelt with Keen and Bennett. He made the diagnosis of poliomyelitis. Roosevelt was old for the diagnosis of poliomyelitis, as it usually affects children. It has been speculated that he may have contracted the virus when he visited a Boy Scout camp at Bear Mountain, New York on July 27, just two weeks before the onset of his symptoms.19 Another consideration was that he was more vulnerable to the infection because of his elevated social status. Polio was felt to be more prevalent among the affluent, who were less likely to be exposed to crowds. Urban children living in crowded conditions were more likely to have acquired natural immunity from subclinical infections when the virus would invade the gastrointestinal tract and produce mild symptoms, if at all. Years later, Eleanor Roosevelt would comment that she was shocked when she received Keen’s bill for $500.18 Roosevelt’s lower extremity paralysis was permanent but did not prevent him from living a vigorous personal and professional life. (Figure 2)

Keen continued to write and lecture throughout his retirement until he died in 1932 at the age of ninety-five. He was a surgeon, an innovator, and a physician to the presidents. F.H. Martin captured the essence of the man in his encomium: “He was a great man, a great American, a great surgeon and a beloved dean of our medical profession.”20

References

- Stone JL. W.W. Keen: America’s Pioneer Neurological Surgeon. Neurosurgery 1985; 17(6): 997-1010.

- Ravit RL and Cauldwell WT. A Man For All Seasons: WW Keen. Neurosurgery 2002; 50(1): 181-190.

- Bingham WF. WW Keen and the Dawn of American Neurosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 1986; 64: 705-712.

- Bland-Allison Act. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org. accessed 6/11/2021.

- Sherman Silver Purchase Act. https://encyclopedia.com accessed 6/11/2021.

- Keen WW. The Surgical Operations on President Cleveland in 1893. The Saturday Evening Post, September 22,1917.

- W.W. Keen and President Cleveland’s Secret Operation. Jefferson Forum, November 2000. http://jeffline.tju.edu/Education/Forum/00/11/articles/cleveland.html accessed 1/4/2021.

- Grover Cleveland: Message on the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, August 8. 1893. American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents1876-1890 accessed 6/1/2021.

- Physicians in William Howard Taft’s Life. http://www.apneos.com/physicians.html.

- Weinstein EA. Woodrow Wilson: A Medical and Psychological Biography, Princeton University Press, 1981, p141.

- Ibid 11, p.166.

- Ibid 11, p.167.

- Ibid 11, p. 168.

- Thomas Jefferson University: Jefferson Digital Commons. Legend and Lore: Jefferson Medical College. Chpt.5 Alumni Who Attended U.S. Presidents, pp139-152. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=105&content=savacool.

- Wilson, Edith Bolling. My Memoir, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis and New York, 1938, p.289.

- Loughlin KR. Hugh Hampton Young and the Bedside of Woodrow Wilson: The President, the Urologist and the First Lady. Urology 2017; 100: 1-5.

- Young HH. Hugh Young: A Surgeon’s Autobiography, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York, 1940, p.400.

- Evans HE. The Hidden Campaign: FDR’s Health and the 1944 Election, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, New York and London, England2002, p.19.

- Anonymous, Dr. Keen Makes Another Appearance. American Heritage, October 1957, Vol. 8, Issue 6. https://www.americanheritage.com/dr.keen-makes-another-appearance. Accessed 6/3/2021.

- Martin FH, William Williams Keen. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1932; 55: 120-123.

KEVIN R. LOUGHLIN, MD, MBA, was born in New York City and raised on Long Island. He is a retired urological surgeon and a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School. He enjoys reading medical history and staying informed on current events. He enjoys traveling, at least he did before Covid-19.

Leave a Reply