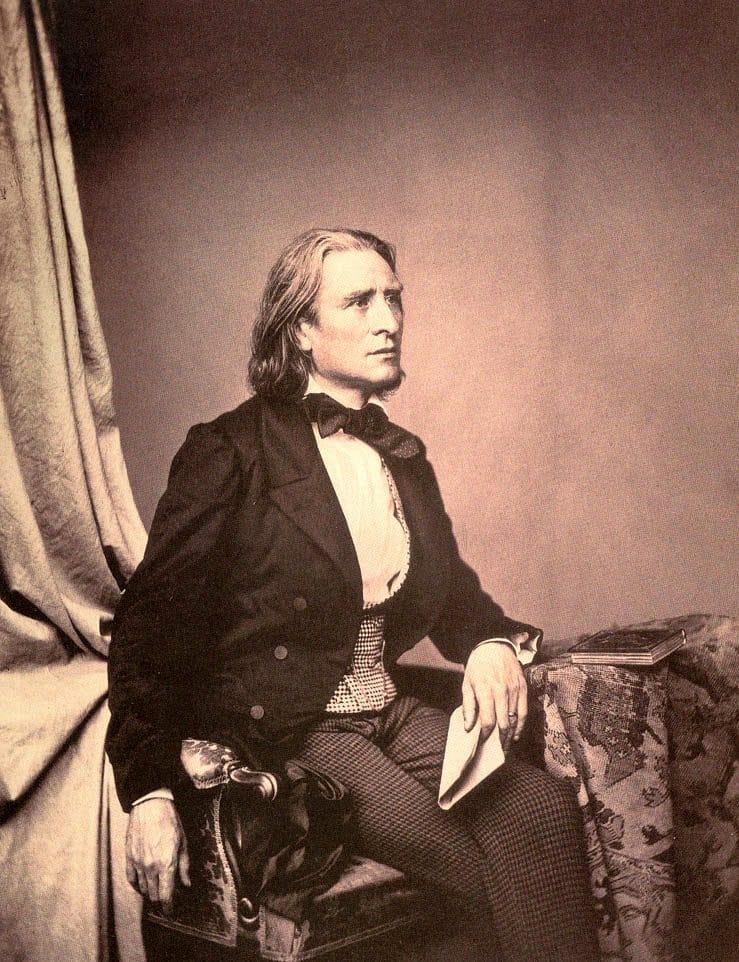

Composer and pianist Franz Liszt. Photo by Franz Hanfstaengl. 1858. Via Wikimedia.

Like Mozart and Mendelssohn, Franz Liszt was a musical prodigy. He played the piano when he was five years old. At eight, he could read difficult music, and two years later he was composing music himself. By age twelve he was ranked one of the best piano players in Europe.1

He was born in 1811 in Hungary, where his father was a steward to the same Esterhazy family that had once employed Joseph Haydn. A sickly child who had not been expected to live, Liszt had his share of childhood illnesses, including a severe reaction to smallpox vaccination. There is a report of an incident in 1835 where he fainted while giving a concert, apparently from a vasovagal attack. Beyond that he seems to have been in good health. He relished drinking coffee and eating smoked oysters. At one time he had an episode of infectious hepatitis from which he promptly recovered. In his “gypsy-like extravagant youth” he ran away with the countess wife of a nobleman and later lived openly with a married princess at Weimar. He was idolized as an artist but also criticized: in Germany for being a Magyar, in Hungary for his Teutonic tendencies (he never learned his mother tongue), and in Paris for not being French born.2 He often drank heavily, and smoked several pipes and strong cheap Havana cigars every day.

At about seventy, old age and excessive smoking caught up with him. Pain and swelling from osteoarthritis of the fingers made it difficult to play the piano. Cataracts impaired his vision, and he had to sit very close to the keyboard. He continued to play the piano and teach, but developed an increasingly debilitating chronic lung disease, causing classical right heart failure, so-called cor pulmonale, and manifested by severe edema or swelling of the entire body, eventually to massive proportions. Then the function of the left side of the heart also became impaired, bronchopneumonia set in, and he died at Bayreuth on July 24, 1886.

His letters, left to the Princess Caroline Wittgenstein, indicate that “at least so far as concerned his own compositions, he was one of the most modest and unselfish of men, one who made it his first aim to help with the works of other composers rather than his own.”3 It has been written that “he was endowed with wonderful powers of penetration, and always seems to been able to adapt himself to the feelings and position of the individual to whom he was writing . . . From the very commencement of his career, when during his early life in Paris (1829), he was giving lessons every day from half-past eight in the morning until ten at night . . . he always had to work hard for a living . . . and in his dealings with publishers, as well as with other people on business matters, his strict conscientiousness and high sense of honor came to the fore.”3 Reflecting the world politics of his times, he wrote that England’s attempt to dominate the sea was a great danger to the peace of the world and proposed a union of the Central European States.4 He early on recognized the extraordinary merit of many of his contemporaries, including Schumann, Wagner, and Berlioz. Liszt was a deeply religious man, who directed that after his death he should be buried in a simple manner, without pomp and if possible, at night. His concluding words were “may eternal light illuminate my soul.”3

Liszt was buried at Bayreuth, the temple of Richard Wagner who had married his daughter Cosima. The chapel erected above his grave was destroyed by shelling in World War Two, but the coffin itself was not damaged. The Hungarian Liszt Society paid for the restoration of the grave but their request to have the body reinterred in Hungary was turned down. He rests in Germany, but his music is played all over the world.

References

- John O’Shea: Was a Mozart poisoned? Medical investigations into the lives of the great composers. St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1990.

- James Huneker. Franz Liszt. Scribner and Sons, New York 1924.

- Letter: The Musical Times and Singing-Class Circular, April 1, 1893.

- Franz von Liszt: The Union of Central Europe. An argument in favor of a union of the States now allied with Germany. In Neus Badische Landes-Zeitung of Mannheim, and in the The New York Times Current History of the European War, Vol. 2, No. 1 pp. 140-143, (April 1915).