JMS Pearce

Hull, England, UK

|

| Fig 1. Harvey Cushing. Cropped from: Harvey Williams Cushing and Sir Charles Scott Sherrington. Photograph, 1938. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain. |

Of the many aspects and contributions of Harvey Williams Cushing (1869-1939) (Fig 1), this sketch concentrates on his identification of a basophilic tumor of the pituitary with adrenal hyperfunction that he called pituitary basophilism1 (Fig 2). It is now known as Cushing’s disease. Symptoms caused by primary adrenal, iatrogenic, and ectopic sources of ACTH are called Cushing’s syndrome.

Born on Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio, Harvey Cushing was grandson of Dr. Erastus Cushing, and son of Dr. Henry Kirke Cushing. He began his career as an intense and determined student at Yale. From there he went to Harvard Medical School, the fifth Cushing in his family to read medicine. In 1896 he trained at the Johns Hopkins Hospital under the preeminent surgeon Halsted (1852-1922). Cushing’s massive capacity for work, surgical skills, and explorations of disease mechanisms were soon apparent,2 though even at this stage his charismatic, sensitive, and provocative personality was evident. When in 1904 he read a paper before the Cleveland Academy of Medicine on “The Special Field of Neurological Surgery,” his vital role in founding American neurosurgery was established. His relentless ambition bore fruit, for he was appointed Moseley Professor of Surgery at Harvard (1912-32).

Like many great men he was a complex character. He was fastidious in dress, a good talker but a bad listener. He had an aura of relentless power and self-belief, but was variously “charming, delightful, tiresome, petty and admirable . . .”18 He related personally and showed ceaseless devotion to his patients. A man of vision and imagination, neurosurgery to him appeared a “cloud-capped tower and solemn temple.” However, he could be irascible, arrogant, and tyrannical to editors, colleagues, and juniors. By means of his meticulous record keeping, attention to detail, and opportunism, he effectively pioneered American neurosurgery3 and despite fierce disputes, trained such talents as Walter Dandy and many brilliant American neurosurgeons.4

He assiduously applied himself to a wide range of neurosurgical diseases.5 As a result he published thirteen books and 300 scientific papers. Most famous was his monograph with Louise Eisenhardt on meningiomas.6

Despite the primitive state of anesthesia and lack of blood transfusion, using his advanced techniques of strict hemostasis, electrocoagulation, and asepsis, he dramatically reduced neurosurgical mortality.7,8 He classified gliomas, extirpated the Gasserian ganglion for trigeminal neuralgia, and resected acoustic neuromas. With the Swiss surgeon Emil Theodor Kocher he unveiled the “Cushing reflex”: the triad of raised systolic and pulse pressure, bradycardia, and irregular respirations that signaled dangerously raised intracranial pressure. In later years he devoted his almost romantic love of medical history to collecting a large, important library, which he donated to Yale University. He also bequeathed the Cushing Tumor Registry, a personal collection of his medical specimens, photographs, and other relics. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1926 for the biography of his friend Sir William Osler,9 who had lived next door to him at Johns Hopkins.

|

| Fig 2. Cushing, The basophil adenomas… 1932. |

Pituitary diseases

The term “ductless glands” was first recorded in The cyclopædia of anatomy and physiology, edited by Robert Bentley Todd in 1849-52, to describe several glandular bodies without ducts e.g. thymus, thyroid, adrenals, and pituitary bodies. The words endocrinology and endocrine appeared after Cushing’s early work, respectively in 1913 and 1914—defined as “Denoting a gland having an internal secretion which is poured into blood or lymph; a ductless gland” (Oxford English Dictionary).

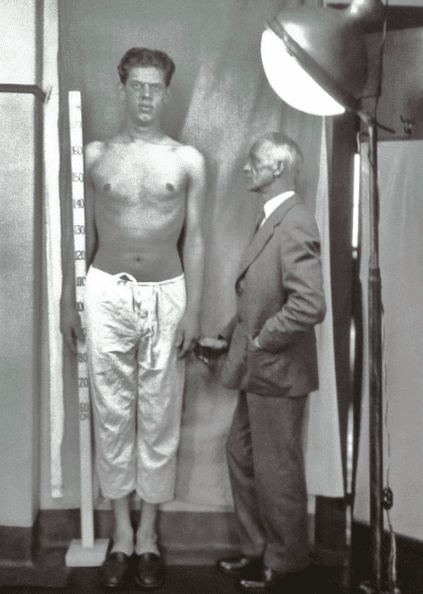

As early as 1906, Cushing observed hypogonadism in patients with pituitary tumors;10 he then produced the first experimental evidence relating the pituitary to the reproductive system.11 Among his patients Cushing observed a condition that had been labeled “polyglandular syndrome.” As an example he cited acromegaly, (Fig 3) which caused changes in both the thyroid and adrenal glands. In 1909, he carried out his first operation for acromegaly via a frontal flap in a thirty-eight-year-old farmer, who made a remarkable recovery.12 In 1910 he gave an account of John Turner, (Case XXXII) a thirty-six-year-old man with gigantism. He also observed diabetes insipidus and correctly deduced it was of neuro-hypophyseal origin. By 1912 he had operated on thirty-seven pituitary tumors.

His celebrated works included meticulous visual field charts and his own excellent illustrations.13,14 These texts enclosed in four papers15 advanced the surgical physiology of the pituitary and its complex neural, endocrine, and vascular linkages with the hypothalamus. He used the pathological classification of basophilic, eosinophilIc, and chromophobe pituitary tumors, ascribing his syndrome to basophilic adenomas.a He also delineated a series of 124 craniopharyngiomas. He applied his surgical skills variously using the transsphenoidal, subfrontal, and transcranial approaches.

In 1910 he examined a woman with signs that were later called Cushing’s disease: (Minnie G). Case 1. (JHH Surgical No. 27140). She was an unmarried Russian Jewess, aged twenty-three, referred by Dr. Stetten of New York, admitted to the Johns Hopkins Hospital on December 29, 1910:

She suffered greatly from headaches, nausea and vomiting sometimes accompanying the more severe attacks. She complained also of aching pains in the eyes which lat- terly had become prominent, . . . shortness of breath, palpitation, purpuric outbreaks, recurring nose-bleeds, and marked constipation accompanied by bleeding piles. A definite growth of hair had appeared on the face with thinning of hair on the scalp. She had become increasingly round-shouldered. Muscular weakness had become extreme . . . Her round face was dusky and cyanosed and there was an abnormal growth of hair, particularly noticeable on the sides of the forehead, upper lip and chin. The mucous membranes were of bright colour despite her history of frequent bleedings. Her abdominous body had the appearance of a full-term pregnancy. The breasts were hypertrophic and pendulous and there were pads of fat over the supra-clavicular and posterior cervical regions . . . The cyanotic appearance of the skin was particularly apparent over the body and lower extremities which were spotted by subcutaneous ecchymoses . . . striae were present over the stretched skin of the lower abdomen and also over shoulders, breasts and hips . . . The systolic blood pressure was consistently high, averaging 185 mm. Hg.1

|

| Fig 3. Cushing and a patient with probable gigantism (labeled acromegaly, from Shin P. Yale J Biol Med. 2011 Jun; 84(2): 91–101.) |

Cushing at first suspected an adrenal tumor, but further investigation led him to conclude that the disease was related to the pituitary gland. No operation was performed. Interestingly, Minnie G. was “in reasonably good health” without specific treatment in 1932; presumably a spontaneous, partial remission. Almost a century later, her surgical records—previously lost—from the Johns Hopkins Hospital, were recovered onto microfilm and reviewed.16

Minnie G. was the first case that Cushing described. He reported in detail the two patients encountered from his own practice and ten similar cases collected from the literature.1

Cushing’s syndrome of adrenal origin was described in Norwegian by Dedichen in 1915 and by Parkes Weber in 1926,17 who referred to a similar (female) patient demonstrated and recorded by Dr. H. G. Turney in 1913. In his 1932 paper he recognized a group of cases that he described as peculiar and sundry polyglandular syndromes,1 which led him to the critical concept that the pituitary was the master gland, the conductor of an orchestra of other endocrine glands:

It was stated at the time that the term “polyglandular syndrome” implied nothing more than that secondary functional alterations occur in the ductless-gland series . . .

That a primary derangement of the pituitary gland, whether occurring spontaneously or experimentally induced, was particularly prone to cause widespread changes in other endocrine organs was appreciated even at that early day, and it was strongly suspected that this centrally placed and well protected structure in all probability represented the master gland of the endocrine series. The multiglandular hyperplasias of acromegaly, so evident in the thyroid gland and adrenal cortex, were already known.1

The “dyspituitarism” that Cushing originally ascribed to pituitary basophilic [micro]adenomas is the result of increased levels of adrenal cortical hormones; it is associated with either bilateral adrenal hyperplasia or adenomas, pituitary tumors (ACTH-dependent), or ectopic (ACTH-independent). Cushing’s syndrome with a pituitary tumor is probably the consequence of excessive secretion of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Genetic studies have led to identification of somatic and germline mutations associated with pituitary tumors.

Cushing married Katharine Stone Crowell, a childhood friend, in 1902. They had five children. His working week of almost 100 hours exacted a toll on his wife and children. A controversial, egotistical figure, he was summed up by Sir Geoffrey Jefferson’s remark about his devoted staff who, “even if they had wounds to lick they were proud of the place where they had acquired them.”18

John Fulton,4 Michael Bliss,3 and Sir Geoffrey Jefferson have written detailed and candid biographies from which I have borrowed freely. The library of the Royal College of Surgeons of England contains A Bibliography of the Writings of Harvey Cushing inscribed and presented by the Harvey Cushing Society on the occasion of his seventieth birthday on April 8, 1939.

As a heavy smoker, he suffered from severe intermittent claudication, and died in 1939 of myocardial infarction while lifting a heavy tome of Vesalius. Interestingly, his autopsy revealed an asymptomatic colloid cyst in the third ventricle. He was interred at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.

End Note

- Prolactinoma, the most common pituitary tumor was not identified until the 1970’s.

References

- Cushing HW The basophil adenomas of the pituitary body and their clinical manifestations (pituitary basophilism) Bull Johns Hopkins Hospital 1932; 50:137-95. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00097.x

- Raffensperger J. Harvey Cushing: Surgeon, Author, Soldier, Historian 1869-1939. Hektoen International. Summer 2020.

- Bliss M. Harvey Cushing: a life in surgery. Oxford University Press, USA, 2005.

- Fulton JF. Harvey Cushing. A biography. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1946.

- Medvei VC. The history of Cushing’s disease: a controversial tale. J R Soc Med. 1991;84(6):363-6.

- Cushing HW, Eisenhardt LC. Meningiomas. Their classification, regional behavior, life history, and surgical end results. Springfield Thomas 1938. (Reprinted 2 vols, New York, Hafner 1962.)

- Cushing HW. Intracranial tumours. Springfield. CC Thomas. 1932

- Pearce JMS. Harvey Williams Cushing (1869-1939). J Neurology 2000;226:1-2

- Cushing H. Life of Sir William Osler. 2 vols. Oxford, OUP, 1925.

- Cushing HW. Sexual infantilism with optic atrophy in cases of tumor affecting the hypophysis cerebri. J Nerv Ment Dis 1906; 33:704-16.

- Crowe SJ, Cushing H, Homans J. Experimental hypophysectomy. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull 1910; 21:127-69.

- Cushing H. III. Partial Hypophysectomy for Acromegaly: With Remarks on the Function of the Hypophysis. Ann Surg. 1909; 50(6):1002–1017.

- Cushing HW. The pituitary body and its disorders. Philadelphia, Lippincott 1912.

- Cushing HW. The functions of the pituitary body. Amer J Med Sci 1910; 139:473-84.

- Cushing HW. Papers relating to the pituitary body, hypothalamus, and parasympathetic nervous system… London : Baillière, Tindall & Cox. 1933.

- Pendleton C, Adams H, Mathioudakis N, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Sellar door: Harvey Cushing’s entry into the pituitary gland, the unabridged Johns Hopkins experience 1896-1912. World Neurosurg. 2013;79(2):394-403.

- Parkes Weber F. Cutaneous striae, purpura, high blood pressure, amenorrhoea and obesity, ofthe type sometimes connected with cortical tumours of the adrenal glands…. Br J Dermatol Syphilis 1926;38:1-5.

- Jefferson G. Harvey Cushing. In: Selected papers of Sir Geoffrey Jefferson.pp. 170-187. London: Pitman. 1960.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Summer 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply