Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

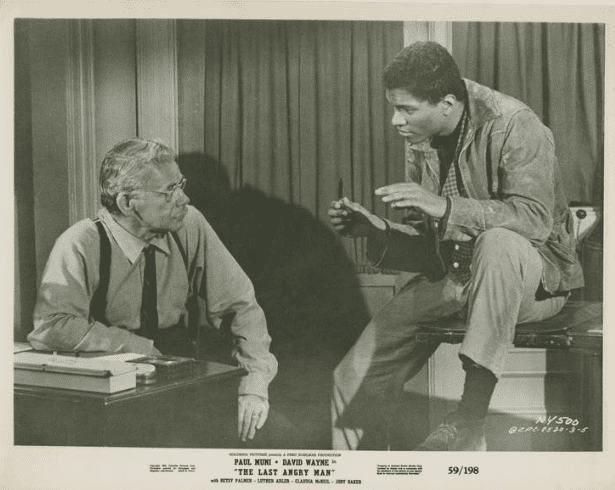

| Still from The Last Angry Man. From the Collection of African American film materials at the Southern Methodist University Library. © 1959, renewed 1987 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |

galoot: an awkward or uncouth fellow.

– Oxford English Dictionary

galoot: someone who thinks the world owes him a living;

someone who wants something for nothing.

– Samuel Abelman, MD

The Last Angry Man1 (1956) is a novel by Gerald Green (1922–2006), author of twenty-two books. Green grew up in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Samuel Greenberg, MD, was a general practitioner in Brooklyn, and the book is dedicated to him. The story takes place in the late 1950s in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

Fifty years ago, Brooklyn was not a trendy home to hipsters and artists, nor a more reasonably-priced annex of Manhattan.

The novel tells the life story of Samuel Abelman, MD, as well as the doctor’s involvement in two unrelated situations. One of them is Dr. Abelman’s dealings with Woodrow Thrasher, an advertising firm executive who needs to create a television show for a sponsor. Thrasher’s idea is “Americans, USA,” a program that features “ordinary people” and the drama in their lives. He reads a small news article about the doctor and thinks that he would be the perfect person to feature in a short film. Readers at the time probably thought that “Americans, USA” was the novelist’s version of a real television program, “This Is Your Life.”

The second interconnected story is about one of Dr. Abelman’s patients, Herman Quincy, a young hoodlum with progressing neurologic signs and symptoms pointing to a brain tumor. This young man is uncooperative and resists attempts to diagnose his problem.

Green’s main character came to the US as a child. His parents were poor Eastern European Jews who settled on the lower east side of Manhattan. His father was a tailor and life was hard. Samuel ran away from Hebrew school on his first day because he objected when the teacher hit him. His first job was as a secretary in a paper company. At the same time, he went to night school for college credits. He later went to a college of physical education and became a qualified gym teacher. He then decided to study medicine and entered Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1908. He loved studying medicine. While he was in medical college his father died, and he had to work nights as a janitor to pay his tuition. He graduated in 1912, got married, and eventually started a general practice in Brooklyn. He stayed in the same place for the next thirty years.

Dr. Abelman is an outspoken man. He considers some people to be “lice,” “galoots,” “bums,” or “bastards.” He uses ethnic slurs but treats his patients with respect and courtesy (if they act respectfully toward him). He treats everyone as an individual. However, he is labile. Patients who argue with him or have long-standing unpaid bills are not appreciated. He reads Thoreau, and has Thoreau’s sense of honesty, but never attains the inner peace of the Walden author.

He worked damagingly long days during the 1918 influenza pandemic and slept three hours per night. He eventually caught influenza himself, was very ill, and had a long convalescence. While he was bedridden, patients left his practice.

Dr. Abelman discusses the problems of Herman Quincy with a neurologist friend, who says, “Do me a favor and don’t worry. Why do you take it personally all the time?” Abelman replies, “Who takes it personally? You think I’ll stay awake nights over it?” The neurologist thinks that Abelman’s answer means that “his friend would not only suffer insomnia over Herman Quincy, but would live with the youth’s ailment forever, for as long as whatever it was . . . would let the patient survive.” This is surely correct, and anyone who knew Sam Abelman would have thought the same.

Dr. Abelman’s best friend and classmate from medical school, Dr. Max Vogel, has attitudes and ideas that clearly contrast with his own. Max Vogel: “Patients are slobs. You got to scare ‘em, keep ‘em scared, and bulldoze ‘em. Don’t make friends with a patient, ever. Don’t even let him think you really care about him. Ah, you’ll never learn, will you, Sammy?” Vogel also clarifies what he believes to be Abelman’s main problem: “. . . that habit of kissing your patients’ asses one minute and hating their guts the next . . .” He has crudely but accurately described Dr. Abelman’s lability.

Abelman agrees to the television program but refuses to participate after he learns that the sponsor wants to reward him with a new house. Although he has wanted to move for many years from the “rotting slum” that Brownsville has become, he refuses. He will not accept “charity,” nor expose himself to the suspicion that he cannot afford to buy his own house. After a counteroffer of no compensation, he once more agrees to do the program. While the television crew is in front of and in his house, Abelman learns that Herman Quincy is at the police station. Quincy was shot in the leg resisting arrest after an attempted rape. The doctor leaves his house and goes with Thatcher to the police station. He climbs the stairs to Herman’s jail cell and suffers a myocardial infarction, a “coronary” in the jargon of the time. Abelman refuses to let an ambulance be called. Thrasher gets him home, and he is attended by Vogel. He dies soon thereafter. Of course, the television program is canceled. The book ends with the burial of Samuel Abelman, MD.

A film made of The Last Angry Man in 1959 was faithful to the main themes of the novel. One small but effective innovation in the film has Dr. Vogel filling out Dr. Abelman’s death certificate. For “cause of death” he writes: 1. Coronary occlusion, 2. Fighting other people’s battles.

Peter Dans, physician and movie reviewer, called the film “the last of the unabashedly laudatory films about general practitioners.” The message of the film, he writes, is “that a single individual can, without fanfare or desire for gain, make a difference in people’s lives.” He concludes, regretfully, “This image of a kindly, selfless solo practitioner was fixed in the minds of the public and of idealistic entrants into the profession for decades after the myth had lost any semblance of reality.”2

References

- Gerald Green, The Last Angry Man. London: Longmans, Green and Co. 1957.

- Peter Dans, Doctors in the Movies. Boil the Water and just Say Aah. Bloomington IL: Medi-Ed Press. 2000.

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. The Last Angry Man was another of the books that influenced his choice of medicine as a career.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply