Stephen Finn

South Africa

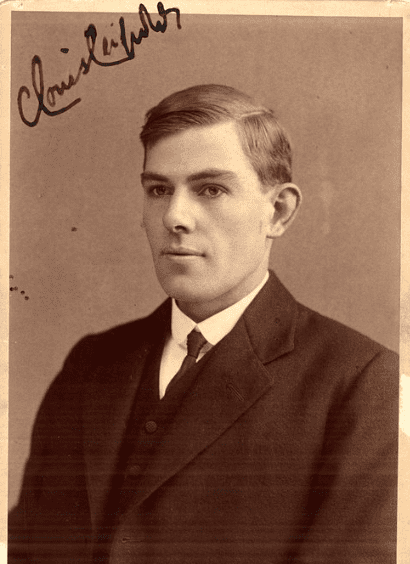

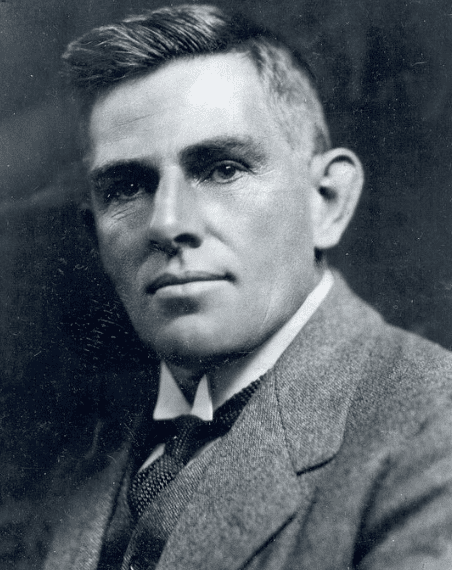

Looking out across a landscape of dramatic mountains and purple and orange sunsets is a small cave. Listen carefully in this desolate place in a western corner of South Africa, and you will hear in the distance the sound of a banjo being plucked. Interred in this cave at his request are the remains of C. Louis Leipoldt—one of Africa’s great polymaths: a multilingual progressive physician, an incisive journalist and a skilled botanist, as well as a brilliant poet and dramatist (writing in Afrikaans), and astounding novelist (these works as well as most of his medical writings in English). He was a man a century ahead of his times with his views on the dietary causes of educational impairment, on the evils of racism, and the abominations of misogyny. He wrote about all of this in his scientific works as well as in his literary creations, and has influenced generations of colleagues and readers.

As we embrace his life and works, let him tell us why it is important that we do this. A lover of Romantic poetry, Leipoldt had an article on “John Keats, medical student” published in the Westminster Review when he himself was finishing his medical studies in London in 1907:

The study of the life and associations of a great writer must always possess an interest, which adds to and enhances the pleasure to be derived from his works. More especially is this study intrinsically valuable where the case concerns the great poet.1

Who was this man who grew up in an isolated village but was fluent in English, Dutch, Afrikaans, French, German, Greek, and Latin; who embraced Buddhist ideas about peace but could quote extensively from the Bible; who read seven detective novels a night; who as a medical inspector of schools in South Africa, the country’s first pediatrician, and the first editor of the South African Medical Journal put forward controversial ideas that were validated in later years; who repeatedly took dozens of poor school children on holiday to the sea; who wrote travelogues and recipe books; who twice won the country’s prime literary prize (the Hertzog Prize) for Poetry (1934) and Drama (1944); who was “the epitome of the Cape liberal humanists of his times, a literary establishment of one”?2 (p. 244 – Stephen Gray “Afterword”)

Christian Frederik Louis Leipoldt (always known as C. Louis Leipoldt) was born on 28 December 1880, the son of missionary parents and grew up in the village of Clanwilliam in South Africa’s Cederberg, several hundred miles north of Cape Town on the way to Namibia. It is an area rich in floral diversity, with a plethora of ancient rock paintings. It was here that Leipoldt’s love for botany was planted and nourished, so much so that as a sixteen-year-old schoolboy journalist, he offered his services to the botanical collector Harry Bolus, who was on a plant-hunting expedition in the area. This was the start of a fruitful association with Bolus, a man of sixty-three, that lasted fourteen years, with a plethora of plants being named after both men—such as the gorgeous shrub with yellow flowers, Wiborgiella leipoldtiana. It was Bolus who encouraged Leipoldt to pursue his medical studies at Guy’s Hospital in London that he funded.

Leipoldt’s collection of letters to Bolus, Dear Dr Bolus,3 written from Clanwilliam, London, New York, and Europe but written mainly during his medical education, shows a man always appreciative of his mentor, and discusses topics ranging from medicine to botany, architecture to painting, music to war. But much of his passion here is centered on literature: his reading and comments range from Virgil to Goethe, Heine and Racine; from Austen and the Brontës to Multatuli, de Quincy, and Irvine; from Shakespeare and Bacon, to the great Romantics, Shaw and Wilde. He read poets, novelists, and dramatists, and with his prodigious memory he quoted easily from writers as diverse as Horace, Dante, Shakespeare, and the Austrian dramatist Franz Grillparzer.

He wrote about serious matters but showed a fine sense of humor, as we see in his comic novel Chameleon on the Gallows,4 as well as in the fraught Stormwrack where he is able to mock himself in a character based on himself:

Young Louis Uhlmann could write Latin, read Hebrew, and quote Goethe and Heine, but was hopelessly at fault when it came to calculating how long it would take for a cistern to be filled or a ditch to be dug according to the conditions so exhaustively detailed in Hamblin Smith’s arithmetic.2 (p. 55)

In this novel, there is also gentle satire when Leipoldt discusses a time of anxiety leading up to the second Anglo-Boer War, and a time of drought; but to some there were evidently more important issues:

The Reverend Mr Mance-Bisley read with keen interest and profound dismay about the first match between the colonial team and Lord Hawke’s visiting team – a match which had resulted in the collapse of the visitors, who had made 79 runs against their opponents’ 115.2 (p. 25)

However, with medical matters he was always totally and earnestly focused, as we see in Bushveld Doctor,5 his brilliant memoir of the time he was medical inspector of schools in which he discusses a place “where beauty and disease are close neighbours”5 (p. 12). He points out how the evident “mental defectiveness” of the children is really a result of malnutrition and malaria; of exhaustion of having to walk miles to class on empty bellies and attend school according to European times in the energy-sapping heat of the day; and how his regimen of “good food, quinine and iron, and abundant rest”5 (p. 42) resulted in rapid improvement. He also insists that it is worrying for children not to “answer back”; in other words, it is a sign of their not being healthy if they are not cheeky at times. In this way, Leipoldt was years ahead of his time.

It is in Bushveld Doctor, too, that Leipoldt is outspoken against homophobia, pointing out that even among birds there is evidence of same-sex attraction, much like Damon and Pythias—a reference to Greek mythology telling of two intimate friends. He insists that homosexuality is everywhere, and its manifestations are no more injurious to communal integrity than are those of heterosexuality.5 (p. 231)

Furthermore, in a profound chapter on “The Right to Die”5 (pp. 201-209), he attacks the concept that a doctor’s main job is to keep somebody alive no matter what; he explains that quality of life should come first and that euthanasia is not a moral offense.

To underline that he was a man of our time is his play about witchcraft, Die Heks (The Witch),6 the first major dramatic work of substance in Afrikaans. Here, he condemns religious oppression, with the drama being in essence an attack on misogyny.

He was also outspoken against racism, as we see in the words of Albert Storam, the Village magistrate in Stormwrack, who, in speaking for Leipoldt, calls it “the foulest and most disgusting of all aristocracies, the wretched aristocracy of skin”2 (p. 178).

This is reflected in his earlier work, Bushveld Doctor, where he rails at discrimination based on race or religion, finding it a product of “intolerance that is based on economic conditions, an intolerance that is in itself an expression of fear, the fear of being unable to withstand competition.” He continues prophetically in an attack against any such legislation:

No civilization buttressed by class legislation that is the result of such fear can defeat the attritive influence of time and culture. . . . It is a pity that those sections of the community in South Africa that are today benefited by such class legislation do not realize that it is a double-edged weapon that sooner or later will be turned against them.5 (p. 188)

Leipoldt was a doctor and writer, who conjured up a harmony for the world around him, a world that he understood was filled with individuals, each able to make their own music. Not everybody, even his friends and colleagues, shared his ideas, but he persisted in his views formed as a boy, honed in his professional life, and expressed in his writing.

As we imagine ourselves standing at this cave where he was buried after his death on 12 April 1947, we remember one of his poems, “Op My Ou Ramkietjie” (“On My Old Banjo”—translated by the present writer)7 (p. 196), that indicates his versatility and individuality, and we understand that it is really Leipoldt we hear in the distance strumming to himself and to the world:

On my old banjo with just one string

I play in the moonlight, just anything.

References

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. John Keats, Medical Student. Westminster Review, April, 1907.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Stormwrack. Ed. S. Gray. Cape Town: David Philip, 1980.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Dear Dr Bolus. Ed. E.M. Sandler. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema, 1979.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Chameleon on the Gallows [Gallows Gecko]. Ed. S. Gray. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 2000.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Bushveld Doctor. Johannesburg: Lowry Publishers, 1980.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Die Heks. Cape Town: Nasionale, 1961.

- Leipoldt, C. Louis. Versamelde Gedigte. Ed. J.C. Kannemeyer. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1980.

STEPHEN MARCUS FINN, DPhil, MA, BA, HED, DSLT, is a professor Emeritus of English. His academic writing has ranged from literature to animal rights, medicine, art, history, and religion. He has also published award-winning plays, novels, and poetry, the main focus being on the outsider in society, school bullying, and animal rights.

Winner of the 2021 Grand Prix Essay Competition & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Special Issue – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply