Jimin Mathew

Bangalore, India

Lucy Samuel

Puducherry, India

In Frida Kahlo: Heroine of Pain (2017), Gavin Aung Than (Gav), an Australian artist, uses comics to capture the lingering pain and excruciating maladies of the famous Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and her evolution towards artistic excellence. This article analyzes the visual and verbal metaphors deployed by Gav to limn the embodied experience of Kahlo.

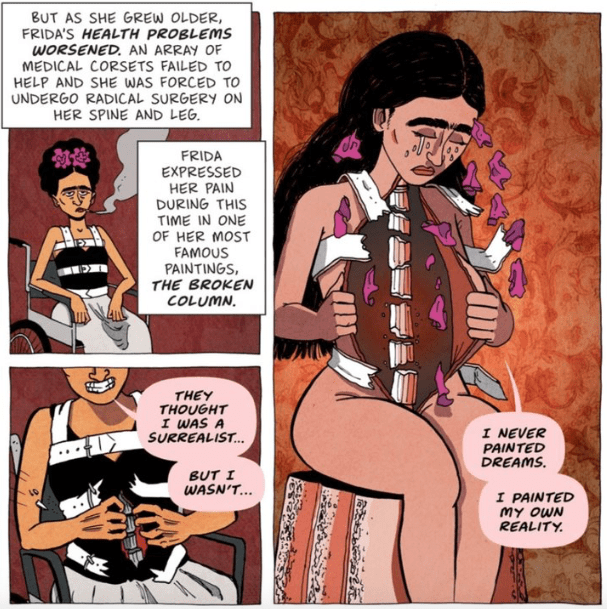

Suffering and pain had always been poignant themes in Kahlo’s art. She had polio at the age of six and was left permanently disabled. At eighteen, she was injured in a bus accident and left with a lifelong ailment and chronic pain. She used her personal experiences as a source of inspiration for her art. Kahlo said, “They thought I was a surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”1 In his comic, Gav captures the influencing presence of chronic pain and suffering in Kahlo’s creative life and artistic journey using the interplay of words and images.

In Figure 1, the blockage is reminiscent of Kahlo’s The Broken Column (1944), painted after spinal surgery. The comic creates structure through a sequential framework of panels and vivid iconographic images. Panel A and B depict consecutive gestures and facial expressions of pain. In panel C, Kahlo tears open her torso to reveal her fractured spinal column. Her purple floral hairband breaks and flutters down in the assiduous struggle, untying her hair which falls back to her waist. The bowed head and droplets of tears on the face illustrate pain. Kahlo’s words, contained in speech bubbles, remind readers that although people considered Kahlo’s art surrealistic, she captured her embodied experiences in her art.

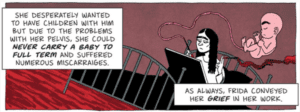

Figure 2 is a single panel depicting Kahlo in the process of painting on a canvas using the umbilical cord of a fetus as the brush. Kahlo paints while sitting on a bed. The prominent color is red. The floor and the fumes of the cigarette she holds in her hand resemble bloodstreams. A reader familiar with the life and art of Kahlo would connect the image to her 1932 Henry Ford Hospital painting after she experienced a miscarriage and which captures a mother who has lost her child and her feelings of hopelessness. Gav’s depiction of Kahlo using the umbilical cord to create art connects to that experience and illustrates her use of unpleasant experiences as fuel for artistic creation.

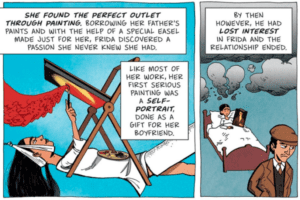

Figure 3 depicts Kahlo in her bed while an overarching easel hovers in front of her. She is bedridden, in cervical traction, and has a plaster cast on her leg. Panel B depicts black clouds overshadowing the bedridden Kahlo, who is holding a self-portrait. Part of the cloud is in the shape of a broken heart; loss and despair are evident in her face. Panel A resembles Kahlo’s Without Hope (1945), painted after a bout of ailments that left her gaunt and malnourished. Gav’s depiction of Kahlo in Panel A is more optimistic than Kahlo’s Without Hope, as the words and facial expressions suggest the rediscovery of Kahlo’s hope and artistic inspiration evolving in pain.

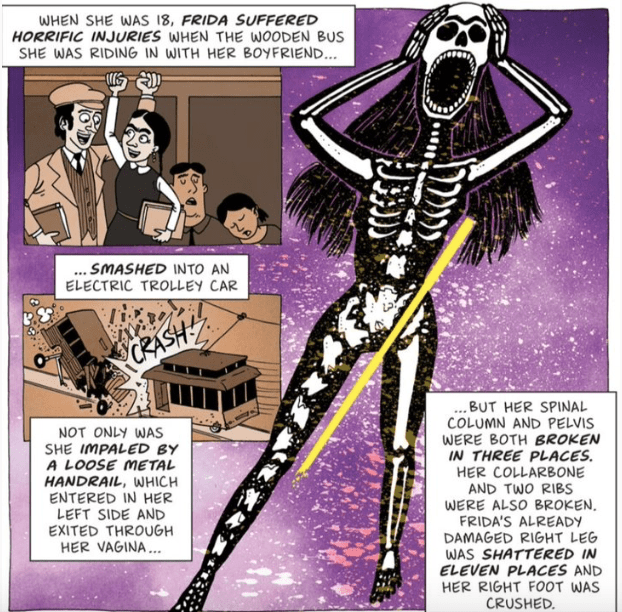

Figure 4 consists of three panels (A, B, and C), with panel C dominating panels A and B. It narrates a key event in Kahlo’s life—her journey with her boyfriend on a wooden bus that ended in the accident that turned her life upside down. The opening events are narrated in panels A and B, overlapping panel C which contains the image of a screaming female skeleton with loose hair, both hands on her head, and a yellow line piercing through her pelvis and vagina. This panel stands as an image-dominant metaphor. The yellow line represents the loose metal handrail that injured her body. Panel A portrays Kahlo’s happy face, which turns to an expression of excruciating pain on the face of a skeleton in Panel C. Kahlo’s paintings What the Water Gave Me (1938), Girl with Dead Mask (1938), Four Little Inhabitants of Mexico (1938), The Wounded Table (1940), Without Hope (1940), and The Dream of Bed (1940), all feature skeletons. Claudia Schaefer (2008), a biographer of Kahlo, points out “her physical and mental health suffered, with depression circling around her as she envisioned death as a skeleton that visited her bedroom each evening.”1 The skeleton symbolizes death and mortality. Gav deploys this motif of the skeleton here to show the experiences of Kahlo in her own visual lexicon.

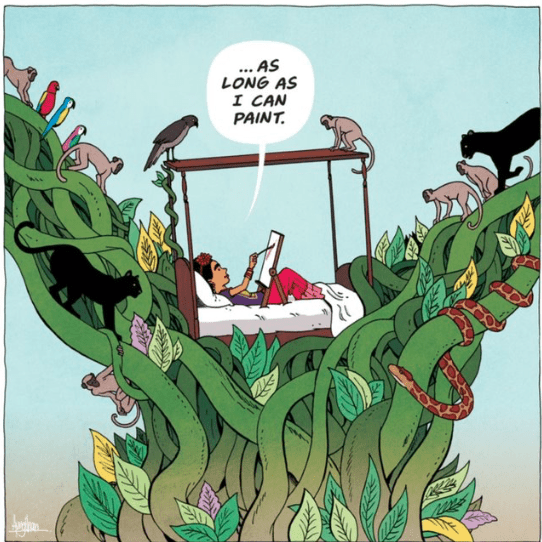

In Figure 5, Gav portrays Kahlo painting in her sickbed on a canvas. She is surrounded by dark green foliage, vines, leaves, parrots, snakes, and panthers. Her hair is pinned up and wound around her head, crowned with flower blossoms. The vivid depiction is reminiscent of a series of self-portraits painted by Kahlo between 1940-1950. These paintings were characteristically filled with bright colors, intricate facial detailing, different hairstyles, and a background of nature that borders her face. The vibrant colors, stylistic head dressing, and beautiful visage could be interpreted as Kahlo resisting aging, disability, and pain. According to Schaefer (2008) these paintings “are evidence of Frida’s increasing attention to the details of her body as she began to feel it slip away in bits and pieces.”1 The more she suffered, the more she decorated her art with vibrant coloration and thriving flora and fauna. Kahlo frees her imagination by estranging herself from her experiences of pain and suffering and placing herself amid the vitality of nature. Gav’s portrait reiterates that art and the act of creation helped Kahlo to cope with her ebbing life.

The stated goal of comic narratives on Gav’s blog Zen Pencils, where The Heroine of Pain was originally published, is to inspire people to live better lives. Gav talks about the inception of his blog thus, “the site started as my desperate attempt to live a life of meaning.”2 Frida Kahlo’s life story and her experiences of pain are familiar subject matter for most readers. However, Gav takes readers’ familiarity with the subject matter and recontextualizes it to bring in his ideas of hope and optimism. Gav has used intertextual references and already popular narratives on Kahlo’s life to introduce the theme of optimism and hope in the comic. “Comics storytelling often makes use of readers’ frames of meaning-making, as well as specific intertextual references and expectations arising from readerly knowledge.”3 Gav presents the biographical story of Frida Kahlo through a lens that inspires optimism. Through a judicious blend of visual elements and verbal narrative, Gav creates a story in which action proceeds from panel to panel—from childhood to artistic excellence.

Image credit: ARTWORK © GAVIN AUNG THAN 2021. WWW.ZENPENCILS.COM/. Re-published with permission.

References

- Schaefer, Claudia. 2008. Frida Kahlo: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Gav. 2017. “Frida Kahlo: Heroine of Pain.” Zen Pencils (blog). Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.zenpencils.com/comic/fridakahlo/. ARTWORK © GAVIN AUNG THAN 2021.WWW.ZENPENCILS.COM

- Kukkonen, Karin. 2013. Contemporary Comics Storytelling. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press

JIMIN S. MATHEW is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Kristujayanti College Bangalore. He is a literary blogger and creative writer. Jimin has published his research articles in several Scopus indexed, national and international journals. His areas of expertise are Liminal Studies, Illness and Literature, Historiographic Metafiction, Energy Humanities, and Gender Studies.

LUCY MARIUM SAMUEL is a PhD research scholar in the Department of English, Pondicherry University. She is an Awardee of Maulana Azad National Fellowship (MAINF), funded by the Ministry of Minority Affairs, Govt. of India. Her area of research is Human Rights Literature.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply