Lealani Acosta

Nashville, Tennessee, United States

|

|

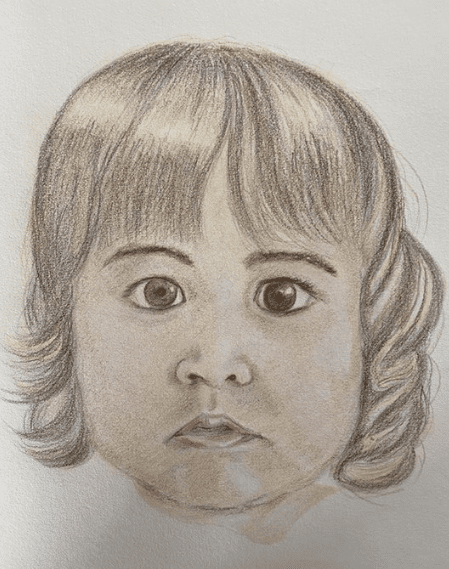

Innocence behind the bangs of a child. Innocence by Lealani Mae Acosta. |

My first glimpse of unfettered grief was through shaggy six-year-old bangs, watching my mother weep, hunched over the toilet and framed by moonlight that cast the pale blue tiles of their master bathroom into darkness.

I glimpsed that grief again as a second-year neurology resident, with my long, black hair pulled back into an omnipresent ponytail. My bangs had long grown out so as not to obstruct my eyes during lumbar punctures.

I was finishing night float and looking forward to a week of elective when I got the news that my mother’s identical twin sister had passed unexpectedly. I found myself flying halfway across the world to stand by her on the uneven hillside of a dormant volcano. Tita (“aunt” in Tagalog, my parents’ Filipino dialect) Ching had battled breast cancer and won several years earlier. She was indefatigable; a cheerful and energetic Franciscan sister who easily transitioned between ministering to tribal peoples on remote Philippine islands to completing her master’s degree in counseling.

Even after decades apart, their voices were so similar as to be disconcerting, down to their hearty and ready laugh. After decades in the US, my mother’s Filipino accent was quite light; my aunt’s, thicker. My mother loves to croon the oldies in her Joan Baez-inspired alto; her sister had been trained as a soprano in the convent. While distinct in their singing, they still shared the same voice.

She had been transferred to work at a convent in Italy, where my own sister and I had visited her earlier that summer, basking in the Tuscan sun as we treated her to a tourist day in Pompeii. Recurrent and now metastatic cancer had come cloaked in jet lag and moving halfway across the world. When the diagnosis came, she went back to the Philippines to spend her final days in more familiar surroundings. My mother rushed to be by her side. The end came swiftly and unexpectedly, shortly after Christmas. The running family joke was that Tita Ching was born first because my mother pushed her out of the womb. She was now, again, the first to go. My mother’s celebration of her fifty-eighth birthday the next month would be without her twin.

I repurposed an elective as a last-minute vacation, thanks to supportive attendings and co-residents. I soon arrived to the oppressive humidity and throng of humanity that is Manila, which I quickly traded for the relative cool and greener pastures in the shadow of the Taal volcano, in the city of Tagaytay, which is where my aunt’s convent was.

Those first few days were a jetlagged blur, but my most vivid memory is of walking by my mother’s side as we accompanied my aunt’s coffin to the convent’s cemetery. My mother had requested we all wear white to the funeral and the only dress I had grabbed from my closet in my hasty packing was made of a thicker synthetic fabric with long sleeves, not ideal for the Philippine heat. My ill-fitting heels stumbled over and punctuated the stubbled earth as I supported my mother on one side, with my sister on the other. We had outgrown our mother in middle school as it did not take much to surpass her five-foot frame, but I felt gargantuan as she leaned heavily against both of us, spent from crying and the anguish of losing her beloved sister.

Two years into residency, I was well acquainted with death and dying as a physician. I had exhausted my matchstick arms on chest compressions at unsuccessful codes. I had been encircled by family members walled around the bedside and extended my hand to distraught fists imprisoning wads of tear-soaked tissues.

During residency, declaring a patient dead is so commonplace as to be routine, but one event stands out in my mind. The afternoon had been quieter than usual, a break from the normally relentless shrill of the neurology consult pager. When I read the nursing update that an elderly patient had finally died, as expected, I invited the student on rotation to come with me.

The patient was on the palliative care floor, perched on top of the hospital, with a hushed tranquility befitting its solemnity. Waning sunlight faded in through the windows. I called the patient’s name. His eyelids yielded easily to my fingertips as I shone my penlight onto fixed pupils. I gently probed for a radial pulse; the paper-thin skin of his still-warm hands had bruised easily. I placed the obligatory stethoscope over his stilled heart. This declaration was more academic, since I was simultaneously explaining to the student all that I was doing. Looking at the clock, I stated the official time. I bid farewell to the patient. I hoped the process was as educational and dignified as it had been the first time I witnessed a resident declaring a patient dead.

Later, I ran into an attending who was teaching a course in which the medical students had to write about a memorable patient experience. The student who had rotated with me had reflected with gratitude for being able to accompany me that day.

Every time I came face to face with mortality, part of me would be transported to that time in my childhood when I saw my mother sobbing for the first time. Her best friend, Auntie Pacit, had died of ovarian cancer. Auntie Pacit was always kind, with a tender smile and a bobbed haircut similar to my own. Hers was my first funeral. She looked peaceful and lifelike in her coffin, with fingers clasped around rosary beads. I ventured a hesitant hand to touch hers. Her skin felt cool and smooth. I recoiled, not out of horror, but from a palpable sense of the gulf between living and not-living.

I found my mother later, perched upon the toilet lid in their bathroom, with inconsolable tears streaming down her face. My memories of this house are fuzzy since we moved about a year later, but I remember the light blue tiles, reminiscent of water, that lined the floor. It was nighttime and she was illuminated by the moonlight that shone through the window, which rendered the aquatic tiles monochromatic. My mother was the strongest person I knew. I had never seen her cry.

When faced with grief, I slip my fingers into the opened hand and impress what little strength I have to share.

LEALANI MAE ACOSTA, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Neurology and a board-certified neurologist specializing in neurodegenerative memory disorders. Her range of publications reflects varied neurological interests, including peer-reviewed research articles in cognitive and behavioral neurology and creative writing, both prose and poetry. Most of her research revolves around cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, including clinical trials for new drug therapies.

Spring 2021 | Sections | End of Life

Leave a Reply